Urban Slavery in Alexandria, Virginia: A Corpus of Critical Urban Historical Sites in Alexandria Today

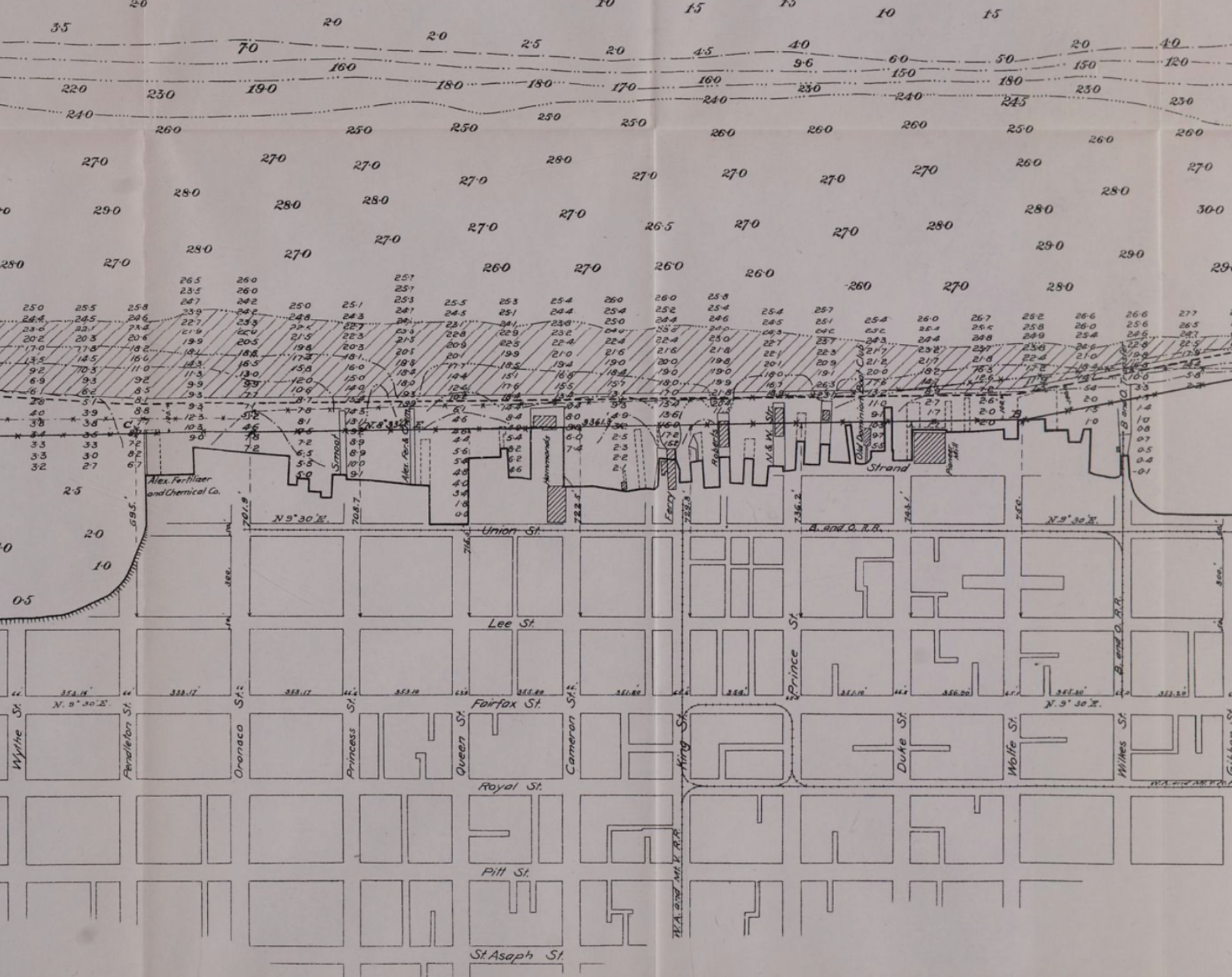

This urban survey provides a rough overview of sites of slavery, imprisonment, and Atlantic slave trade in Alexandria, Virginia. It touches sites in the city along the waterfront, within the urban fabric of the city, as well as on the periphery of Alexandria located in DC's periphery.

Preface

This urban survey provides a rough overview of sites of slavery, imprisonment, and Atlantic slave trade in Alexandria, Virginia. It touches sites in the city along the waterfront, within the urban fabric of the city, as well as on the periphery of Alexandria. Many of the places in this corpus today have been transformed or redeveloped by building projects in the city. Carlyle Wharf now stands as a center of commerce and culture along the Potomac, serving patrons that use the water taxi to travel from DC to Alexandria. The Alexandria Gazette exists as a news bulletin rather than a formal paper to share information around the city. The house of Dr. James Craik—the personal physician of George Washington and close friend—is inhabited by a new family, with only a signpost to commemorate the importance of the site and its connection to Washington. Other sites remain more overtly connected to Alexandria’s history of urban slavery. The Franklin & Armfield Slave Jail, Edward Home’s Slave Jail, and Joseph Bruin’s Slave Jail all retain a detailed archeological record of the atrocities that happened there despite being covered by new buildings and foundations. There is a plethora of reminders of the complex, often patchwork, layout of Alexandria’s history of urban slavery and its imprint on its urban landscape. However, some sites stand out.

The Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery and Memorial were commissioned and re-preserved by the city within the last fifty years. The memorial represents a more concerted effort by scholars, urban planners, and Alexandria’s urban leadership to commemorate and acknowledge the harms of the city’s past. These sites are designed to directly engage with the city’s history of urban slavery and to invite others—within and beyond Alexandria—to grapple with the history of American slavery so close to the nation’s capital. This is the central idea of this paper. Although DC’s initial charter prohibited the practice of slavery in the city, Alexandria’s retrocession back to Virginia represented a clear effort for the state to preserve its economy built upon enslavement. The juxtaposition of these two cities, across the Potomac River, saddling the political burden of a nation, could not disagree more strongly about a central issue. This corpus of critical historical locations not only uncovers the contentious and alarming history of slavery only a few miles from DC but also invites further scrutiny and scholarship into the ways slavery is etched on DC’s urban landscape. I foresee that future scholarship will undoubtedly complicate the history presented below. But I present this survey of historical Alexandria as a potential beginning in a much larger conversation, inviting further inquiry into how slavery, industry, and politics are entrenched deep within the history of American democracy.

Alexandria Waterfront – Carlyle Wharf

Just at the foot of Cameron Street, Carlyle Wharf was once the home of John Carlyle and John Dalton’s ship docks that extended along the shore of the Potomac. In 1759—ten years after the founding of the town—the Alexandria trustees granted Carlyle and Dalton the right to build a landing point for ships on the Potomac River. From then on, the docks served as a hub for the transatlantic slave trade, during which over 900,000 African men, women, and children were delivered to the American colonies from abroad (“African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route,” n.d.). The Slave Trade in the Chesapeake peaked during the 1750’s and in the years following, the slave trade was directed towards other colonies like the Carolinas, Georgia, and areas of New England (“African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route,” n.d.). In the 1770s, the growing anti-slavery movement in the region made it challenging for the Atlantic slave trade to continue in the Chesapeake and resultingly the Maryland Assembly banned the slave trade in 1774. Virginia followed suit a few years later (“African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route,” n.d.). Although the demand for slaves during this time went down as agrarian economies slowed in the rural Chesapeake area, Alexandria continued to receive and export slaves throughout the region. The prohibition on the import of slaves passed in 1807 preventing the transatlantic transport of slaves to America but did little to stop the trade in Alexandria. Slave merchants in Alexandria relied on imports from Brazil and Cuba, where the slave trade was still legal, to provide slave labor to southern states in the 1820s (“African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route,” n.d.).

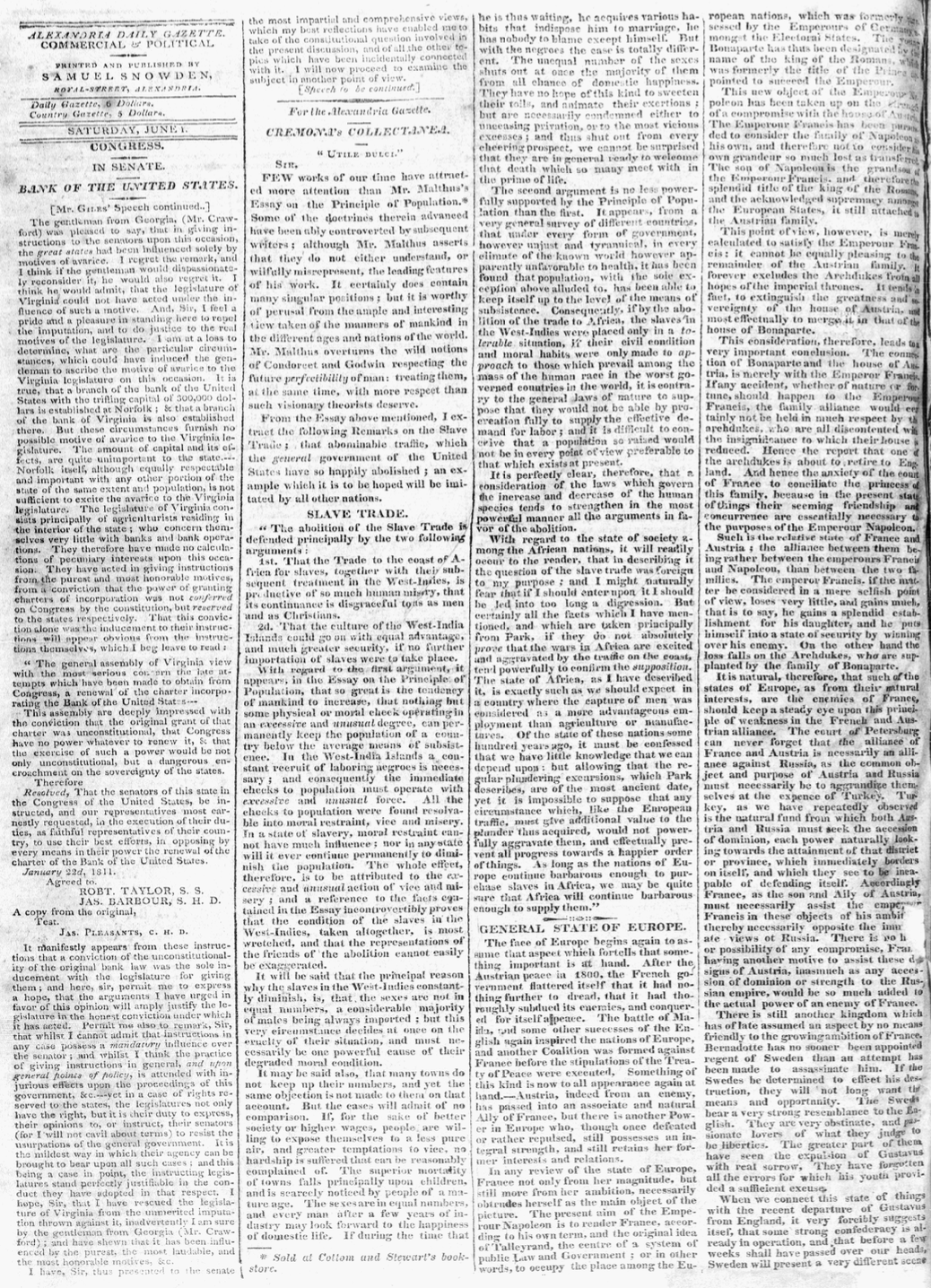

Alexandria Gazette – 310 Prince Street

The Alexandria Gazette was a critical newspaper in Alexandria during the time of slavery. Not only did it post offerings for the sale of slaves in the city, but it also produced prominent critiques of the institution of slavery during the mid-1800s (Colby 2015). In 1829, the Gazette printed a quote from Pennsylvania Congressman Charles Miner that staunchly critiqued the institution of slavery as “cruel and unjust” (Loncarevic 2012). However, even as late as 1864, the paper advertised the sale of slaves for between $3,025 and $6,500 on the Richmond Market (Colby 2015). The Alexandria Gazette most notably exchanged fierce debates about the retrocession of Alexandria from Washington, DC, a choice that would definitively protect the city from the policies of slave abolitionism enacted by Congress (Loncarevic 2012). In 1862, the Alexandria Gazette was burned down after the paper published an account of civil unrest at a nearby church. The Reverend, who was arrested after his sermon, refused to perform a prayer for the President of the United States and was arrested by Union soldiers who were outraged by the Reverend’s indignation (“A Holy Dispute: The Alexandria Gazette Burning of 1862” 2020). The inaccurate reporting of the Gazette ultimately got it in trouble and the paper took a while to recover after the fire (“A Holy Dispute: The Alexandria Gazette Burning of 1862” 2020). The paper nonetheless came back to full force and began its regular operations where it resumed contentious debates about the institution of slavery. Against the backdrop of Alexandria’s embattled urban landscape, the Gazette indexes key opinions during the 19th century about the perpetuation and exploitation of slavery in the region.

House of Dr. James Craik – 210 Duke Street

James Craik was the personal physician to George Washington and a well-known slave owner who violated an important regulation, causing the people he enslaved to file a lawsuit for their freedom. Laws dating back to 1778 required slave owners to disclose the origin of the slaves they brought with them from other places (Nicholls 2000). Craik, who migrated from Maryland in 1786, failed to take the required oath attesting to the origin of the slaves he brought with them. Joseph Harris, Betsy Scarlett, and Ann Williams fought Craik for their freedom (Nicholls 2000).

Their case began in the Alexandria Hustings Court, moved to the Dumfries District Court, and then were appealed by Craik to the State Appeals Court. Harris, Scarlett, and Williams won their case and both William and Harris continued to live in Alexandria from 1809 and 1810 (respectively) onwards (Nicholls 2000). Although the origination laws from 1778 allowed an increasing urban population of free Africans throughout the late 18th century, the manumission laws of 1782 were far more effective at liberating urban, formerly enslaved people in Alexandria (Nicholls 2000). By 1810, almost 878 individuals in Alexandria and beyond had been manumitted through deeds, wills, and other legal acts; however, many young, enslaved folks had to wait many years before they were freed (Nicholls 2000).

Alexandria Quaker House – Wolfe and S St. Asaph (SWC)

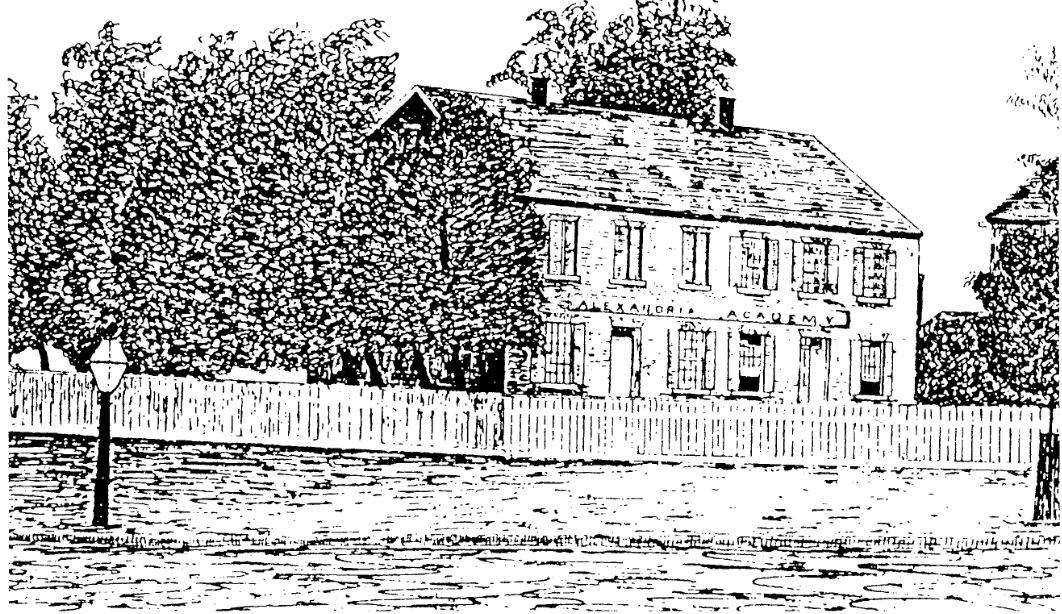

The Alexandria Quaker House at Wolfe and South St. Asaph Street became an important home for pro-abolitionist ideologies inspired by the Quaker faith. The meeting house, built for $4,000 in 1811 was used by local Friends until 1872 when it was converted into a school (Crothers 2005). Before then, ongoing meetings of the convention steadily blended religious doctrines within the Quaker faith with the political rhetoric of the time. “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” became both political and religious rhetoric for local Alexandria Friends (Crothers 2005).

Over time, the members of the Alexandria Quaker House began to pledge “‘themselves to use all lawful means’ to relieve and protect ‘such as are illegally held in bondage’” in the region (Crothers 2005). The society eventually acted on these intentions and in 1795, sued the city for a volatile statue that forced slaves to pay $100 to the slaveholder if the filed suit for their freedom and lost (Crothers 2005). In response, the Alexandria assembly passed an even harsher statue that sentenced to death anyone who helped slaves achieve their freedom or incite rebellion (Crothers 2005). Although the Quaker society continued to fight against increasingly harsh pro-slavery legislation, the society began to dwindle until it eventually burned out in the late 1800s. Their petitions and early anti-slavery rhetoric, however, would live on.

Franklin & Armfield’s Slave Prison – 1315 Duke Street

The Franklin and Armfield Slave prison on 1315 is embroiled in complex history and dispute. Tenants living in the building were evicted in 1979 and was purchased by new owners in 1984 with the intention of renovating the increasingly ramshackle structure. Prior to beginning construction, the owners agreed to an inspection to uncover more information about its history and occupation during the 19th and 20th centuries. Archeologists examined three areas of the house and found results consistent with early accounts of the slave prison on the site. The remains of whitewashed brick walls revealed a line of postholes that indicted where enslaved people ate their meals. A well was found in the yard alongside a brick chamber that was thought to have led to a basement or underground holding cell. A trash pit outside the walled enclosure held various organic artifacts and wine bottles (Skolnik and Lee 2024). Old 1834 accounts of the slave prison described events and customs in the slave jail that were largely consistent with the archeological record uncovered in the late 1980s (Skolnik and Lee 2024).

The 1315 Duke Street slave prison was the site of horrible brutalities in 1837, including the murder trial of Dorcas Allen, an enslaved women from Georgetown. She was living as a free woman in Georgetown in 1837 until one of her enslavers died, named Anna Davis. On Anna’s deathbed, she made her husband, Gideon Davis, promise to free Allen after she died. Gideon Davis freed Allen but never issued her manumission papers. Gideon remarried to Maria Davis, and after his death, Maria Davis married Rezin Orme who sold Dorcas Allen and her four children to slave trader James H. Birch for $700. Orme had no deed or right to own Dorcas Allen or any of her children. On the night that Allen was imprisoned at 1315 Duke Street, she killed her two youngest children and attempted to kill her remaining two children as well. However, she was caught and eventually put on trial for murder. She was found not-guilty, likely because the Jury sympathized with Birch and because if found guilty, Birch could not re-sell Allen for profit (Skolnik and Lee 2024).

The story of 1315 Duke Street is ingrained with tragedy. Early in its lifetime in 1832, the slave traders Isaac Franklin and John Armfield transformed the site into an epicenter of industrious slave trading (Skolnik and Lee 2024). But despite its dark past, the site was bought by the Northern Virginia Urban league in 1997 to advance their mission of equal opportunity for Black and African American residents in the region. 23 years later, they sold the site back to the City of Alexandria where it remains today (“History of 1315 Duke Street,” n.d.).

Edward Home’s Slave Jail – 1500 King Street

Edward Home’s Slave Jail is also a critical site on the 1500 block of King Street in Alexandria. Home came to Alexandria in 1850 when the slave trade was largely abolished throughout the region. Original records show that Home acquired the land for his jail and began building a series of structures on it as well as a slave jail with a slate roof. The year after his arrival, he advertised the site in the Alexandria Gazette and offered to purchase slaves for his slave jail; his advertisement also offered to “board them” for 25 cents a day (Skolnik and Lee 2024). By the end of the year, Home’s property was listed for auction and was bought in November 1851. Archeological evidence within the site from 2007 indicates that Home, his family, and the enslaved people imprisoned there were some of the earliest occupants on the site. However, the archeological records poorly represent the history of Edward Home’s slave jail because of its short-term status; its operation from 1850-1851 leaves little archeological artifacts behind. The short-term lifetime of Edward Home’s slave jail makes it a difficult historical landmark to study; future building projects would have destroyed much of the archeological record from the 1850’s (Skolnik and Lee 2024). But the transience of the site has everything to do with its urban positionality. The “boom and bust” pattern of urban economies—even urban slave economies like Home’s in Alexandria—leave gaps in our understanding of urban slavery from the past.

Joseph Bruin’s Slave Jail – 1707 Duke Street

Located at 1707 Duke Street, Joseph Bruin’s Slave Jail is an important site in the understanding of urban slavery in Alexandria. Bruin was formerly employed at another slave jail, located at 1315 Duke Street and established this jail down the road from 1844 to 1861. A series of excavations in 2007 and 2008 uncovered a series of postholes that might have belonged to the barracks used to house enslaved people. They also found evidence of a washhouse structure and a series of pits that might have been used as a kitchen by enslaved people (Skolnik and Lee 2024). This slave jail was most widely known to house Emily and Mary Edmonson during 1848 who attempted to escape the city aboard The Pearl. A series of organic remains near the jail indicate the Joseph Bruin utilized cheap cuts of meat and oysters to feed the people he imprisoned at 1707 Duke Street (Skolnik and Lee 2024). This site of imprisonment and enslavement in the city of Alexandria provides additional details that give us a better understanding of urban slavery. While slaves often moved in and around the city, the use of slave jails to remove enslaved people from the urban landscapes deepens the harmful, historical impact of the practice on Alexandria.

Edmonson Sisters Memorial – 1701 Duke Street

The Edmonson Sisters Memorial is located on the same site as Joseph Bruin’s Slave Jail on 1707 Duke Street which is now occupied by an office building. The memorial commemorates Mary and Emily Edmonson who tried to achieve freedom on board The Pearl. After their failed attempt, they were imprisoned at the Joseph Bruin Slave jail, but Harriet Beecher Stowe—author of the notable book Uncle Tom’s Cabin—wrote their story into the pages of the text (Ater 2019). During the evening of April 15th, 1848, the sisters tried to escape slavery on board The Pearl; originally, they planned to take seven slaves with them so they could leave Washington, DC. But eventually, word got out about their escape plan and many more enslaved people joined in their plans. The boat eventually held around 77 men, women, and children who were trying to escape from slavery, but inclement weather and rumors of their plans got in the way.

The following morning, over a dozen white men left the Georgetown waterfront to try and recapture the escaped slaves; they were found and imprisoned on April 18th (Ater 2019). Riots soon overtook Washington, DC and mobs of white men began threatening the lives of the imprisoned slaves. By the end of the week, a Baltimore slave trader named Hope Slatter purchased 50 of the imprisoned slaves at the Bruin Slave Jail in Alexandria. The Edmonson sisters were eventually purchased by Joseph Bruin and transferred them to Baltimore where they were to make their way to New Orleans, but the rise of yellow fever brought them back to Alexandria where they were sold into domestic slavery. Their journey became a rallying cry for other slaves in the city who looked to them and their planned escape with a sense of hope and enduring admiration for their bravery. Henry Ward Beecher and members of the Methodist Churches around New York eventually raised enough money to purchase the freedom of the Edmonson sisters, who were emancipated on November 4th, 1848 (Ater 2019).

Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery

The Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery of Alexandria emerged out of necessity during the Civil War. During that time, Alexandria was occupied by Union Soldiers who prohibited the practice of slavery in the region. This caused a dramatic influx of enslaved folks from slave states into the city; the new unprecedented population density of the city caused illness, disease, and the deaths of many thousands of emancipated slaves living in shantytowns in Alexandria (Ater 2019). By 1864, nearly 1,200 black individuals had passed away and overburdened the municipal cemetery that was dealing with a historic influx of bodies needing proper burials. In February of that year, the city commissioner confiscated land from its “pro-Confederate owner and designated it as a cemetery” (Ater 2019). The American Baptist Free Mission Society appointed Reverent Albert Gladwin—an African America minister from Connecticut—as Superintendent of Contrabands, or the formerly enslaved. He oversaw the cemetery from 1863 to 1865 and during the five years of the cemetery’s operation, 1,879 people were buried in marked graves (Ater 2019).

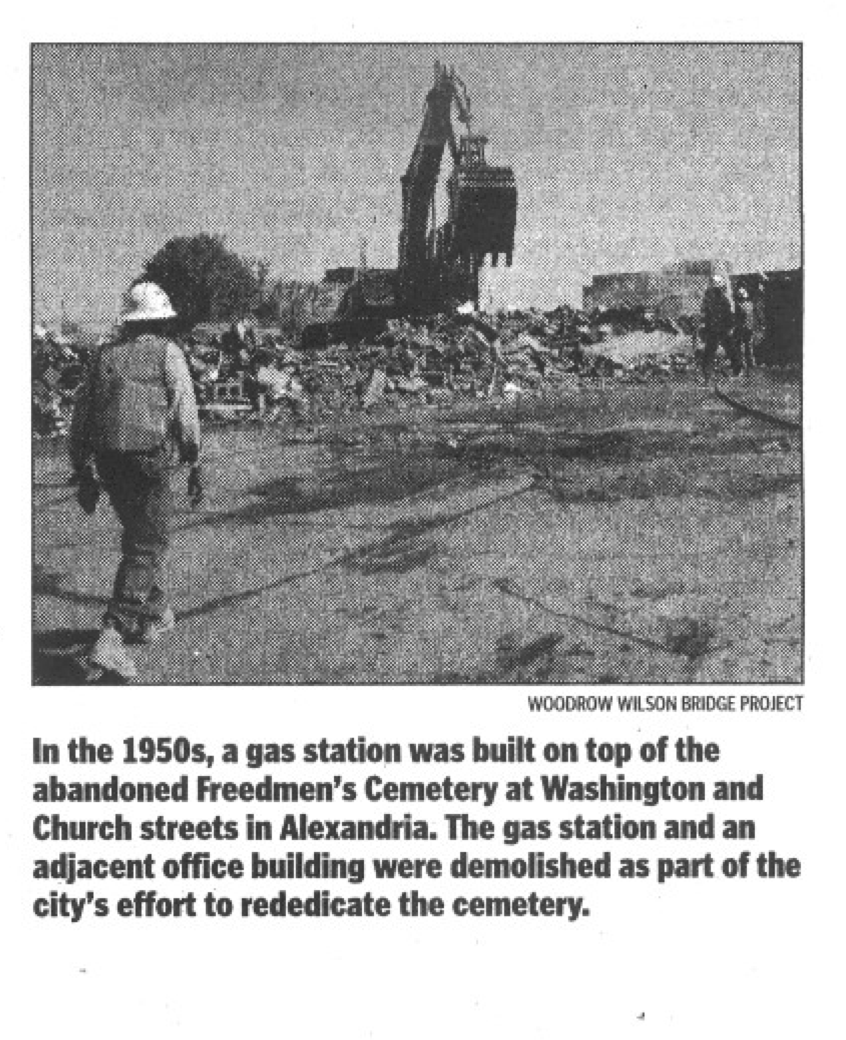

Initially, African American Soldiers serving in the military during the civil war were also buried at the site until they were disinterred and reburied at Arlington National Cemetery in 1865. After that, the upkeep of the cemetery declined; until 1939, the cemetery appeared on city maps but was later overtaken by commercial development. A gas station was built on the site in 1955 until historian Wesley E. Pippenger found Gladwin’s records in the city archives and began excavation of the site. The gas station was razed in 2007 and over 540 graves were identified and re-preserved at the cemetery site (Ater 2019). With the help of local Quaker groups of Alexandria, the city promoted the significance of the cemetery and its context within the larger history of slavery in the city (Ater 2019).

Contrabands and Freedmen’s Memorial

The Contrabands and Freedmen’s Memorial, including the Path of Thorns and Roses, became a critical urban site to commemorate the volatile history of urban slavery in Alexandria. In 2008, the City of Alexandria held a design competition to create the memorial and a public park to commemorate its history of slavery. Local architect C.J. Howard won the design competition among a pool of over 200 international designs. His work called for the construction of a large monument to an African American Union solder at the south end of the cemetery and was designed in response to a confederate statue from 1889 that stands eight blocks north of the site (Ater 2019). The steering committee ultimately ended his plans citing material constrains and Howard eventually designed a “framework for a detailed site design.” The memorial park today includes contemporary gravestone for the unidentified dead, a Place of Remembrance constructed using four walls made from Virginia sandstone with inserted bronze plaques (Ater 2019). Some of the walls include narrative texts and the names of people buried from Gladwin’s own records; living descendants are indicated on two stone walls while the other two have “bas-relief narrative scenes” from slavery and abolition history periods (Ater 2019). Another design competition was held in 2011 to create an additional installation at the site of the Memorial. Artists Erik Blome, Mario Chiodo, and Edward Dwight won with their design of a large bronze statue with male and female slaves positioned to look like “a double helix” to “represent the common DNA of mankind” (Ater 2019, citing Russ).

This site concludes this analytical corpus of critical sites in the history of urban slavery in Alexandria. The stories held within the city—the tragedy, struggle, and conflict—narrate a history of urban slavery that is both hidden and overt within the urban landscape of Alexandria. Its contentious positioning only a few miles outside the nation’s capital in Washington, DC emboldens slavery’s fundamental entanglement in the early political and social history of the United States. Slavery, indeed, existed and was challenged in Washington, DC; but the stories uncovered here in Alexandria reveal a much larger, more profoundly alarming landscape of urban slavery that expands from the monuments, across the Potomac, and into the heart of this Virginia city.

Bibliography

“African American Waterfront Heritage Trail Historical Marker.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=239718.

Alexandria Gazette. June 1, 1811. Readex AllSearch.

Ater, Renée. “The Memory of Slavery in the Urban Landscape of Alexandria, Virginia.” In Traces and Memories of Slavery in the Atlantic World. Routledge, 2019.

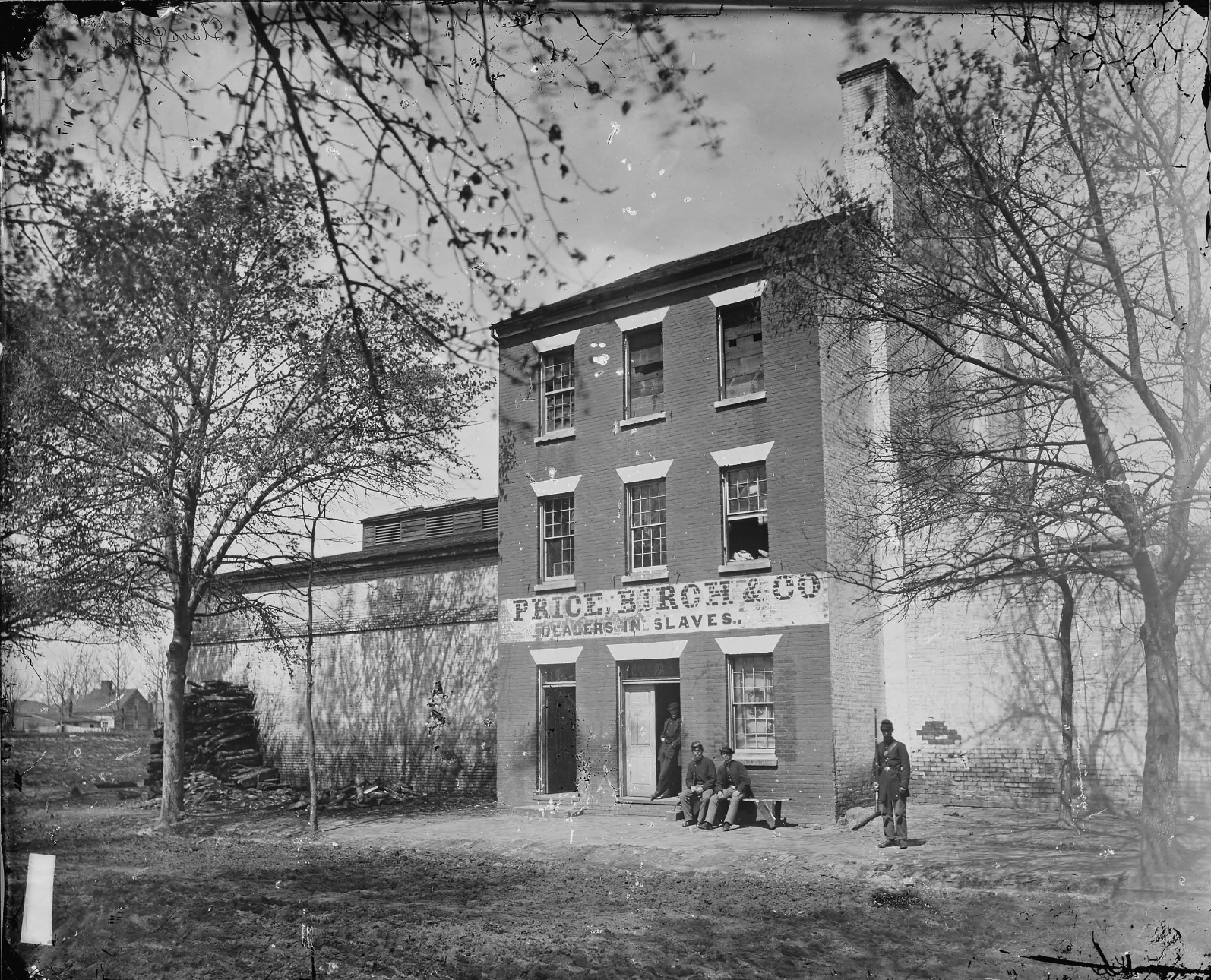

Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.) 1858- ? “Slave Pen of Price, Birch & Co., Alexandria, Va.” The National Archives, ca. –ca. 1865 1860. 528808. National Archives.

City of Alexandria, VA. “African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-sites/african-american-heritage-trail-north-waterfront-route.

City of Alexandria, VA. “Historic Alexandria Maps.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/basic-page/historic-alexandria-maps.

City of Alexandria, VA. “History of 1315 Duke Street.” Accessed October 29, 2024. https://www.alexandriava.gov/museums/history-of-1315-duke-street.

Colby, Robert. “The Continuance of an Unholy Traffic: The Virginia Slave Trade During the Civil War.” Dissertation, University of Carolina, Chapell Hill, 2015.

Crothers, A. Glenn. “Quaker Merchants and Slavery in Early National Alexandria, Virginia: The Ordeal of William Hartshorne.” Journal of the Early Republic 25, no. 1 (2005): 47–77.

Davis, Audrey P. Alexandria at War 1861-1865: African American Emancipation in an Occupied City. Alexandria, Virginia: Office of Historic Alexandria Press, 2023.

“Document | Serial Set Maps | Readex.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=SSMAP&sort=_rank_%3AD&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=%22alexandria%20virginia%22&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A0F9739B96A15CDC0%40SSMAP-121D3C4961D3BAA0%40-1160A8F88D20D318%40&firsthit=yes.

Dr. James Craik House, 210 Duke Street, Alexandria, Independent City, VA. HABS VA,7-ALEX,3-. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. Accessed October 29, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.va0096.photos.

Exterior of the Price, Birch & Co. Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia. Graphic. Liljenquist Family Collection (Library of Congress). Alexandria, Va.: Bowdoin, Taylor & Co., 204 King, Cor. Columbus Street, 1861. LOT 15158-1, no. 1698 [P&P]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.83351/.

Foster, Thomas A. “Lessons From Abingdon Plantation at Reagan National Airport in Washington, DC.” In Traces and Memories of Slavery in the Atlantic World. Routledge, 2019.

Goodman, Christy. “Residents Gather to Rededicate Freedmen’s Cemetery.” Washington Post, May 13, 2007, sec. Alexandria.

Heidemann, Mary Ann. “The Identification, Preservation and Interpretation of Slave Sites in the United States.” In Routledge Companion to Global Heritage Conservation. Routledge, 2019.

“Hi-Res Interactive Map of Mt. Vernon, Fairfax County, VA in 1890 | Pastmaps.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://pastmaps.com/map/mt-vernon-fairfax-county-va-usgs-topo-1890.

Jackson, Maurice. “Washington, DC: From the Founding of a Slaveholding Capital to a Center of Abolitionism.” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 2, no. 1 (May 1, 2013): 38–64. https://doi.org/10.1179/2161944113Z.0000000004.

Jenkins, Virginia. “EDWARD STABLER, ‘A KIND FRIEND AND COUNSELLOR’: A QUAKER AND ABOLITIONIST IN ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA: 1790-1830,” 1995.

Loncarevic, Eldar. “Land of the Free, Home of the Slave: The Rise of Slave Markets in Alexandria, Virginia, 1800-1850.” History Matters, no. 9 (May 2012): 7–30.

“[Map of Alexandria, Virginia] | Library of Congress.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/resource/gvhs01.vhs00032/?r=0.212,0.661,0.931,0.494,0.

Member of the Washington bar, Washington, etc. Maryland. Laws, etc. Virginia. Laws, and D.C. Ordinances Washington etc. The Slavery Code of the District of Columbia : Together with Notes and Judicial Decisions Explanatory of the Same. Washington [D.C.], United States: L. Towers & Co., printers, 1862. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DS0103022401/SAS?sid=bookmark-SAS&xid=76290745&pg=5.

“National Archives NextGen Catalog.” Accessed October 26, 2024. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/528808?objectPage=3.

NCinDC. Bruin’s Slave Jail. September 18, 2008. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/ncindc/2869453949/.

Nicholls, Michael L. “Strangers Setting among Us: The Sources and Challenge of the Urban Free Black Population of Early Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 108, no. 2 (2000): 155–79.

OAH, ByGeorgetown U. History 396 students & their Prof Chandra Manning in cooperation with the NPS &. “Escaping Slavery, Building Diverse Communities.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 13, 2020. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/98843655e3474b9ab19a2afe250f0f22.

Offbeat NOVA. “A Holy Dispute: The Alexandria Gazette Burning of 1862,” July 26, 2020. https://offbeatnova.com/2020/07/26/a-holy-dispute-the-alexandria-gazette-burning-of-1862/.

Old Town Home. “Around Old Town: The Historic 1796 Dr. James Craik House.” Accessed October 29, 2024. https://www.oldtownhome.com/2013/7/18/Around-Old-Town-The-Historic-1796-Dr-James-Craik-House/.

Pywell, William R. “Slave Pen in Alexandria, Virginia.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14653903.

Quaker Meeting House, 1811. [University of Pennsylvania Press, Society for Historians of the Early American Republic], 2005. The Lyceum Museum. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30043604.

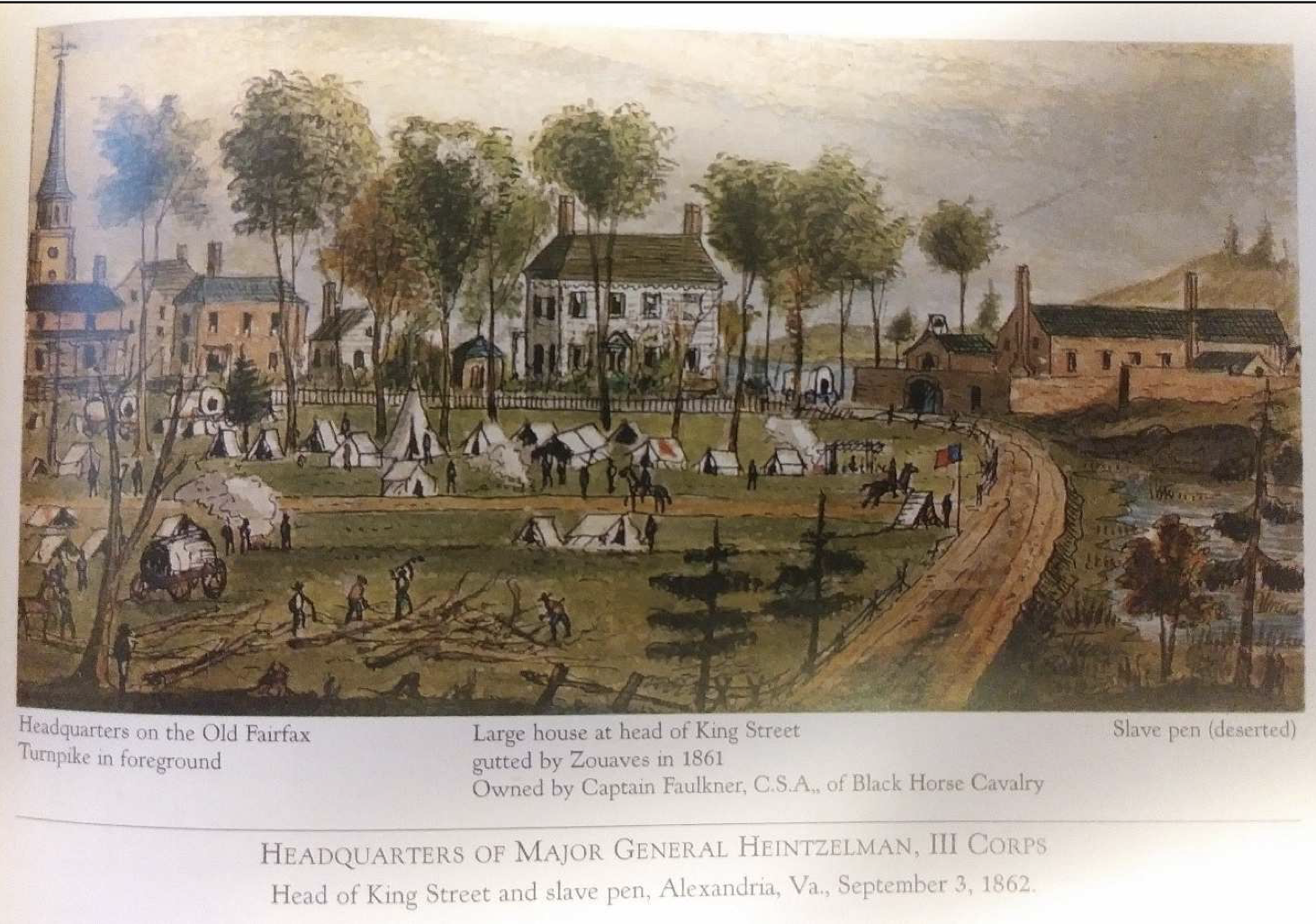

Robert Knox Sneden. Headquarters of Major General Heintzelman, III Corps. September 3, 1862. Illustration. Virginia Historical Society.

Skolnik, Benjamin A. “Building and Property History: 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Virginia.” Survey. Alexandria, Virginia: City of Alexandria, n.d.

Skolnik, Benjamin A., and Samantha J. Lee. “Ideologies in Tension and Moments of Change: The Slave Jail at 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Virginia.” Historical Archaeology 58, no. 2 (June 1, 2024): 409–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-024-00501-y.

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Va. January 1, 1861. Graphic. LOT 4161 [item] [P&P]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3b04851/.

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Va. January 1, 1861. Graphic. LOT 4161 [item] [P&P]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print. https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3b04850/.

Thomas, William G. III, Kaci Nash, and Robert Shepard. “Places of Exchange: An Analysis of Human and Materiél Flows in Civil War Alexandria, Virginia.” Civil War History 62, no. 4 (2016): 359–98.

Underwood, John Cox. Speech at Alexandria, Va., July 4, 1863. Washington, United States: McGill & Witherow, 1863. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DS0103009429/SAS?sid=bookmark-SAS&xid=f9139b24&pg=7.

Washington Post Company, and Allan B. Slauson, eds. A History of the City of Washington, Its Men and Institutions. Washington, D.C: Copyright by The Washington Post Co, 1903. https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.historyofcityofw00wash/.

WHHA (en-US). “The Complexities of Slavery in the Nation’s Capital.” Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-complexities-of-slavery-in-the-nations-capital.