The Language of Temporary Architecture, Immigration, Migration, and Asylum at Candler HERRC: Arabic and Spanish Linguistic Pragmatics in Translation

This paper will explore the nature of ephemeral urban spaces with special attention to the physical, linguistic, and political barriers that complexify the asylum and migrant experience for new arrivals in New York.

Abstract

Working at the New York Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) has foregrounded critical issues in city planning and international migration. From working in the field at HERRCs (Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers) around the city to filing briefs with interdepartmental organizations, the connection between urban planning, architecture, and citizenship is at the center of New York’s immigration approach. This paper will explore the nature of ephemeral urban spaces with special attention to the physical, linguistic, and political barriers that complexify the asylum and migrant experience for new arrivals in New York. Using Nasser Abourahme’s work as an anchor text to explore the ephemerality and history of the “camp,” this paper will dive into scholarship that discusses the evolution and philosophy of architecture within cities that play a role in migrant and immigrant experiences. It will consider how these spaces produce narratives about the migrant/immigrant identity while addressing how these divisions act upon questions of citizenship, permanence, and emergency through additional scholarship. Beyond literature, this analysis largely will draw on elements of the refugee experience to supplement discussions about the camp and ephemeral architecture. Semi-fieldwork will mobilize Arabic and Spanish linguistic pragmatics—or how language is used—as a vector of additional analysis that can reveal how spoken discourse challenges narratives of temporariness and emergency by coupling the significance of words in translation with their use within the HERRC. Spoken conversation thus provides a compelling vector of analysis to determine how migrants, immigrants, and asylum seekers challenge the temporariness of their identities and the places they live. This paper subsequently finds that Arabic and Spanish linguistic pragmatics directly challenge the nature of spatial and political temporariness of the immigrant, migrant, and asylum seeker identity by incorporating terminology of home, family, and friendship when this language is examined in situ and post-facto through translation. As a result, the way people speak about HERRC within these sites and the way they are categorized by city officials and the public presented is sharp disagreement but offers hope that these sites can and do offer a form of home and close living that is ignored in previous scholarship about these sites.

Keywords

Immigration; asylum; migration; urban planning; architecture; New York City; linguistics; pragmatics; semantics; translation studies; Arabic; Spanish.

Introduction

At ten in the morning on a Thursday, I arrive eager, underprepared, and sleep-deprived at the HERRC on 42nd Street, tucked behind the cacophony of buses and street cars that barrel down Broadway Avenue only a few yards away. My colleagues have told me the proper name of the building is Candler HERRC, but the faint words “Roosevelt Hotel” are still visible just a few feet above the doorway. My work at Candler HERRC began when I started my internship at the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) in early October. I began my work at Candler HERRC by helping new arrivals apply for New York City IDs (IDNYC) to get access to important resources like healthcare, discounted subway fare cards, and English classes. Doing this work involved drawing on my linguistic experience learning Spanish in my childhood and my recent studies in Arabic language and culture since late June (during which time I gained intermediate proficiency in the language). My experiences working with residents of Candler HERRC over two months surfaced important considerations about how these spaces are spoken, addressed, and narrated in verbal speech. Beyond the HERRC, its environment is spoken about within the context of temporary space and emergency architecture. HERRCs are, by nature, temporary spaces that offer sixty days of stable housing for new arrivals in the city. At Candler HERRC, residents are mostly single men coming from Spanish, Arabic, Wolof, Fulani, and French-speaking regions in South America and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Given my language background, I was asked to work mostly with residents from Arabic-speaking areas of the MENA region and constituents from South America.

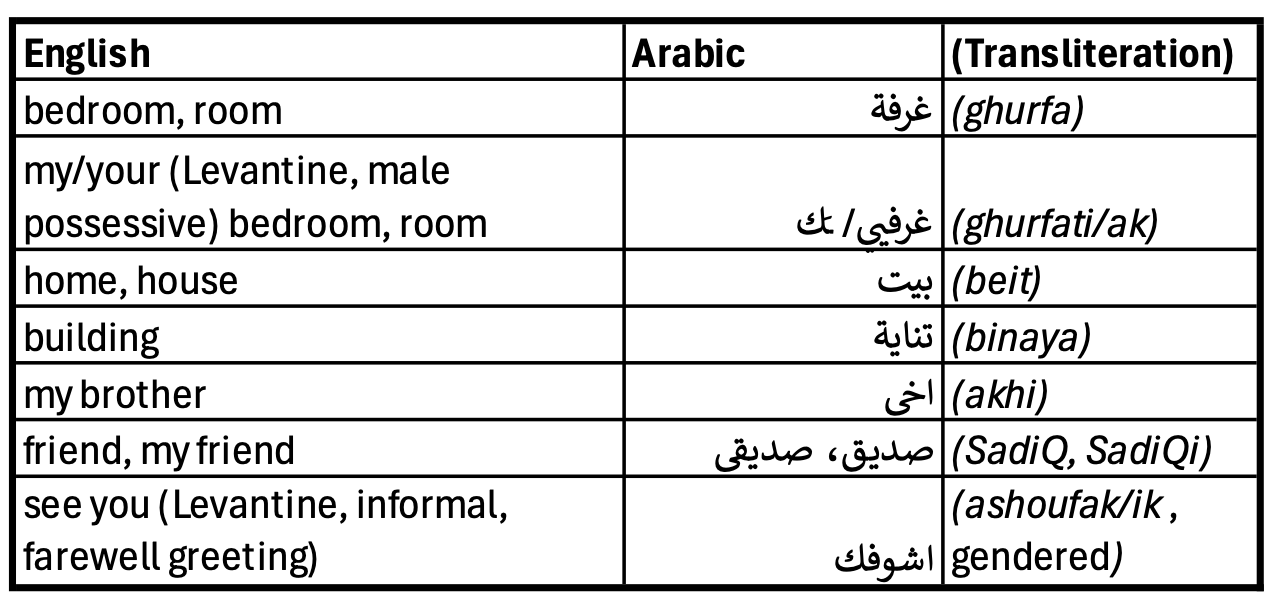

Over time and with careful reflection, the words and word choices that I adopted began to reflect the dominant ways that residents spoke about their experiences in the HERRC. Words that mean “house,” “home,” “bedroom,” and “brother” emerged in my Arabic in response to similar language reproduced by HERRC residents. Doing so achieved two things. Firstly, it allowed me to gain rapid fluency with the exigent vocabulary used to discuss the HERRC in non-English terms. Second, it revealed how linguistic pragmatics confront the dominant narratives about emergency and temporary political identity attached to the HERRC by people who live and work beyond them. The way the New York residents and city administration discuss and criticize HERRCs is rooted both in the tenuous political identity of their residents and the fact that these spaces are temporary themselves. For instance, after Mayor Adams opened two new HERRC sites in Queens and Brooklyn, city NGO leaders denounced the effort and called for more “permanent housing, not more temporary shelters and HERRCs” (Targeted News Service 2023). This further produces narratives that HERRC centers are inherently temporary despite some of the language that maintains otherwise. The language used in non-English linguistic pragmatics may be a altered or affected by the act of translation. One might assume a lack of congruent words in Arabic and Spanish that mirror the vocabulary used to describe the temporariness of identity that HERRCs create. However, this is not the case. Arabic’s root system and Spanish’s vast linguistic word bank offer terminology to describe the acute nature of these HERRCs and the purpose they have in the context of New York City politics. The Hans Wehr Arabic and any Spanish dictionary offer starting points to find these terms.

Given this central predicament—the disconnect between Arabic and Spanish pragmatics used to describe space and the way these spaces are built and categorized in the city—this paper puts exigent literature about the architecture of migration in conversation with language. My work at MOIA understands that language is a nuanced and important vector of analysis to understand how people grapple with central questions of identity and temporary residency. It finds that Arabic and Spanish linguistic pragmatics directly challenge the spatial and political temporariness of the immigrant, migrant, and asylum seeker identity constructed and magnified by places like HERRCs. It pays attention to the terminology of home, family, and friendship within these languages observed in situ during on-site work in Candler HERRC and post-facto when these terms are translated. Thus, the way people speak and articulate their experiences in HERRCs disagrees with the way they are categorized by the city. Language in and of space shows how people recategorize their experiences living in HERRC environments and imbue them with narratives of home and permanence of identity. It offers some hope that these sites can and do provide a place where the home can be conceptualized and invoked through speech, despite what previous scholarship might say. This paper begins first with a review of current literature about the subject matter, putting existent scholarship in conversation with one another and the subject of this research. It will shift into a brief discussion of the methodologies of this paper, namely the semi-fieldwork conducted to produce the findings of the paper. Following, it will address the findings of this fieldwork using linguistic pragmatics and Arabic and Spanish translation to understand narratives about temporary space. Finally, it will discuss these findings and their significance and conclude with the implications of this work and areas of future study.

Literature Review

This section of the paper will consider a small segment of the larger corpus of literature that discusses refugee camps, the politics of migration and the body, and the specific architecture of temporary spaces divided into three sections. The first situates Abourahme’s work on the camp in context and explores other narratives about “campization” that pertain to refugee sites. The second will discuss the politics of migration, citizenship, and the body generated by these questions about the camp and experiences therein. The final will address specific examples of immigration architecture—including refugee settlements and camps—as well as the larger design of temporary spaces that house these groups. In the end, it will position these works in the landscape of this paper and transition to the methodologies of this paper.

The Camp

In his work, Abourahme draws differences between the various versions of the camp that exist in the contemporary world. He references many ideas of the camp that have proliferated over time, including: “homeless camps, recreational camps, university campuses, military camps, refugee camps, internment camps, summer camps, labor camps, fat camps, tech camps, protest camps, naturist camps, boot camps, and terrorist camps.” (Abourahme 2020, 35). In so doing, Abourahme differentiates forms of the camp and criticizes the ubiquity of the form today. However, underlying these different manifestations of the camp is a central ideological thread. Abourahme argues that this “topological elasticity of the camp form” grows more elastic as the colonial borders that construct the spaces of the camp become more concrete (Abourahme 2020, 35–36). It is this elasticity and proliferation, combined, that keeps the presence of the camp as a “ubiquitous political technology of our age of permanent crisis” and produces a “theoretical allure of its figure” and a sense of its indispensability and unavoidability in “our contemporary political grammar and theory” (Abourahme 2020, 35–36). Thus, for Abourahme, the notion of the camp is a fixed issue because of the expansion of the form of the camp over time and how anchored it is within the language— “grammar and theory”—of the political world. The idea of the camp becomes both a subject of language and political study, supporting further the linguistic undertaking of this paper. But situating these spaces around the urban question also reveals how the existence of these sites is perpetuated and driven by the systems that they employ themselves.

Kreichauf weaves together a compelling analysis of refugee camps and the central predicament of these places by presenting literature about the differences between the terms “refugee camp” and “asylum center” used to describe centers of migration in the Global South and Global North, respectively (Kreichauf 2019, 250). This substantiates the ideological separation between the ways society considers the nature of refugees and asylum seekers depending on their localization. But by interrogating the separation of these two forms of viewing refugee centers, Kreichauf brings the notion of the refugee camp—usually associated with narratives of the Global South—to the North. He does so by using the process of “campization” to explain how refugees and residents within camps are forced to maintain a presence there because policy restrictions prevent residents from seeking places beyond the camp. Kreichauf writes that campization is “a process in which the recent tightening of asylum laws and reception regulations have resulted in the emergence and deepening of camp-like characteristics of refugee accommodation in European city regions” (Kreichauf 2019, 250). It is this principle of “campization” in the Global North that helps contextualize the work of HERRC centers that do work to provide shelter for new arrivals, but do not substantially provide pathways to independent mobility beyond these spaces. In a way, they constitute places born out of a crisis to address a need to support new arrivals but do not offer a permanent way to integrate these folks into American society.

Politics, Citizenship, and the Body

To begin, Di Cesare speaks about the philosophies of migration and the way it questions sovereignty, the state, and the symbolic nature of movement across countries manifests in the city. At the beginning of her work, Di Cesare grapples with some of the central contradictions of places like Ellis Island that seem to contradict all forms of US policy (Di Cesare and Broder 2020) The main argument of this contradiction stems from the widespread consensus that ensued when criteria for naturalized citizenship emerged in the early history of America. People imaged an inherent right to citizenship by simply being born within the boundaries of the “New Continent” (Di Cesare and Broder 2020, 9). In this view of citizenship, “not everyone in the world seemed suitable—despite the words engraved at the foot of the Statue of Liberty” for a place within the fabric of America’s growing population. Ellis Island, therefore, “forgot about its exile and preferred to exercise its sovereignty” by adjudicating the kinds of people who could gain access to the borders of America (Di Cesare and Broder 2020, 9). This idea of sovereignty produced a US citizenry who could “hold themselves to be the legitimate owners, and thus authorized to deny or limit” access to spaces inside the country (Di Cesare and Broder 2020, 13). The right to property and the privileged status of belonging within America became a guarded right by people born within its national borders. For people who seek asylum or hospitality within the city, they must exist as people forced into a condition of existing as people who embody both “foreigner and resident” at the same time (Di Cesare and Broder 2020, 216). Such an identity—the “resident foreigner”—is rooted in a spatial-temporal instability that is inherently detached from the possession territory that might be affixed to the role of a resident. This coheres well with the work of Bruno Meeus, Bas van Heur, and Karel Arnaut, who provide ideas that connect similar urban infrastructure that runs up against migrant identities and the political theories that overshadow them.

First, they discuss the notion of arrival infrastructures, which are categorized as parts of the urban landscape “within which newcomers become entangled on arrival, and where their future local or translocal social mobilities are produced as much as negotiated” (Meeus, van Heur, and Arnaut 2019, 1). This means places like HERRCs, intake centers, and judiciary locations where the legal status of new arrivals is determined for their time within these urban areas. Expanding on this notion of arrival infrastructures, Meeus et al. introduce three main theories that help position the work of this paper in broader political considerations. They first introduce the politics of directionality, which refers to ways that migrants “are linked to a range of places due to their particular biographies, social attachments, and legal statuses” (Meeus, van Heur, and Arnaut 2019, 1). The shifting nature of these biographies might change this politics of directionality, but the way migrants align and contrast one another based on national origin and legal status helps situate the work of this paper in shared language and translation. They also introduce a politics of temporality that questions how people image citizenship and a right to permanence through mobility and “migrants’’ search for forms of stability” (Meeus, van Heur, and Arnaut 2019, 22). Indeed, in these cases, the work of HERRC centers becomes clear in the politics of temporality precisely because they are impermanent spaces that grant residents sixty days of stability.

To understand further the significance of this idea within the landscape of the HERRC, it is worth considering how the body can witness restrictions on and the delimited purpose of spaces. Amy Gowen argues that “access to public space and rights to roam are built upon long, established histories of violence and exclusion” (Gowen 2021, 4). This excerpt conceptualizes what it means to move through space and the city and how its design and delimitations—like the HERRC centers that are constructed—exclude migrant populations and other refugee groups that fall outside of planning paradigms. The way this access is determined poses important questions that are addressed by Gowen. Who is the “we” that can move through such designed and planned spaces? Who can invest a place with meaning and whose body has the right to exist in these zones? (Gowen 2021, 12). Considering the city as an element in this predicament allows this analysis to interrogate how the camp might interact with movements and behavior specific to refugee and migrant populations. Does the camp invite a sense of free movement by supporting new arrivals with the agency to explore their new home? Or does it push these experiences to a “disappeared” part of the city so beyond public space that those who live there have no concept of their freedom to move and exist within the public spaces of the city? We might reasonably ask how public space, the camp, and the city collide under Abourahme’s conceptualizing of the camp under theories of global crisis. Gowen’s arguments and the focus of this paper align well with Andrew Herscher’s considerations about the political subjectivity of refugees and migrants.

Herscher unpacks many of the issues present when one takes time to consider the landscape of the arrival city and the people who petition and seek asylum in cities around the world. First and foremost, Herscher addresses the political subjectivity of the refugee who is placed within a larger network of political turmoil and therefore deemed part of it: “The crisis assigned to the presence of refugees, however, also registers the status of the refugee as a political subject” (Herscher et al. 2017, 2). This draws an important line to the politics of architecture as both a design principle and a practice deeply rooted in the subjectivity of politics produced by and through national attention. In other words, the way we conceptualize national borders (or a lack thereof) is what categorizes the refugee as a political subject; how we attend—or pay attention to—the relevancy of borders is what drives the political subjectivity of the refugee. By neglecting to recognize national borders, especially as they limit movement, the identity of the refugee embodies a “preeminent collective form” of this subject of borders in contemporary politics (Herscher et al. 2017, 2). Herscher moves next to the consideration of the Arrival City as a concept that connects the humanitarian focus of refugee camps with the provision of services to new arrivals within urban environments. This is articulated by Herscher as a site where refugees and migrants exist within a capitalist city that “has now become a solution to humanitarian emergencies” (Herscher et al. 2017, 16). In this manner, one can see how the nature of humanitarian intervention is taken on by urban space as it assumes the role of the arrival city. At the same time, the arrival city—as a place that offers temporary shelter—juxtaposes the constant discourse about immigration policy by the government and news outlets. The arrival city as a site for 60 days of refuge contradicts the constant engagement with global migration policy that happens regularly within the city. This poses a unique point of comparison for the subject matter of this paper, which deals mostly with New York. Its nature, perhaps as an arrival city, is complicated by some of the ostensible architectural distinctions that enforce a separation between the arrived bodies in the city and the rest of its urban space.

This is conceptualized most strongly by Ragne Øwre Thorshaug, who considers the architecture of asylum centers in Norway and argues how the nature of these centers reproduces border structures within the city. Refugees might be a political subject that exists in contrast or in collective opposition to border politics, but that does not mean these borders are nonexistent. Many proponents of the architecture of asylum centers point to how the buildings are cost-effective and standardized to make a national approach to the asylum question more consistent across sites. But the drive to make asylum centers and temporary living places less attractive contributes to a “production of both an external and an internal border regime” (Thorshaug 2019, 223). This means that the sites where people live and reside as they seek asylum in a new country enforce not just the spatial boundaries of a nation but the internal borders that exist between asylum seekers and their new site of living. Hidden inside the Roosevelt Hotel, Candler HERRC exists in a similar fashion. Its antiquated appearance and modest aesthetics enforce the national circumference of America by separating asylum seekers from the broader US citizenry. But it also draws an internal border by producing friction between residents, workers, and officials who deliver resources to these sites. Consequently, this analysis will also take up the notion of internalized borders to situate language as a vector of post-crisis, or the idea that translation and linguistic pragmatics can overcome the discourses of political separation enforced by HERRCs in New York City. Using this consideration and the ideas of the camp introduced by Abourahme and complexified by the idea of politics and citizenship, examples of refugee and emergency architecture become the subject of the next section of scholarship in this literature review.

Temporary Architecture and Spaces of Emergency

Mirjana Lozanovska brings out critical questions about the nature of architecture as a discipline embedded “within structuralist linguistic frameworks, and from the behavioral emphasis of people–environment studies” (Lozanovska 2015, 5). This normative architectural thinking that Lozanovska mentions produces issues when we conceptualize architecture as a significant element of the migrant experience. If people conceptualize “‘architecture’ and ‘building’ as significatory entities related to language rather than structured and transparent frameworks,” a more nuanced interpretation of architecture’s connection to migrant identities might emerge (Lozanovska 2015, 6). Language in these spaces can reveal how people “assimilate, adapt, remake, construct and express the architectural process of resettlement” (Lozanovska 2015, 217). Combining attention to language and spoken words might confront the sense of otherness enforced by spaces where migrant identities are exteriorized. This might especially manifest within constructed spaces that include more than one ethnic group, language, and culture, as is the case with HERRC centers and refugee camps. It is this attention to the architectural language of assimilation on which this paper builds. By considering the way architecture engages discourse about itself and the way other people speak of these places, this scholarly endeavor pays attention to how patterns of linguistic pragmatism, translation, and interaction might complicate perceptions of migrant architectural spaces as zones of inherent political crisis.

Miguel Pérez and Cristóbal Palma craft a unique approach to studying migration in their work documenting the experiences of residents in the Nueva Esperanza camp in Santiago, Chile. Their work foregrounds important ways that individuals living within these camps construct the space of the camp on their own. This calls forward the idea of autoconstruction, where migrants build houses and cities “step-by-step according to the resources they are able to put together at each moment” (Caldeira 2017). Using this idea of autoconstruction as an ethnographic starting point, Pérez and Palma conclude that this practice in Santiago has two defining elements in the Nueva Esperanza camp. The first is that the appearance of camps built by migrants is a product of “practices of city making that are permeated with a market rationality” or an attention to economic gain (Pérez and Palma 2021, 28). Secondly, they argue that migrants “articulate ethical and political narratives about their conditions of exclusion which express their aspirations for belonging and incorporation” to be recognized as urban subjects (Pérez and Palma 2021, 28). This envisioning of the camp environment brings out careful questions about how migrant spaces are constructed by residents of HERRCs in New York. These spaces might be organized by city officials and municipal organizations, but they are navigated internally by residents themselves. Spaces where interactions happen, phone calls occur, and translation transpires is adjudicated by migrants rather than the employees who work on site. Thus, clear parallels exist between Pérez and Palma’s work in Santiago and the phenomena that are observed in HERRCs in New York. Furthermore, similar narratives about “ethical and political narratives” about exclusion help concretize the desires of these HERRC residents for belonging. Pushing back against rejections for city services—like healthcare and ID documents—allows HERRC residents to petition for a more permanent sense of incorporation within the city.

Megan Sheehan builds on this study by considering Santiago, Chile in a different way. She anchors her work in the idea that “the city is a thing in the making” and practices of inhabiting such cities “are so diverse and change so quickly that they cannot be easily channeled into clear uses of space” (Simone 2010). Sheehan’s work foregrounds the idea that “small discrete spaces are invested with new meaning” in the context of housing for migrants in the city. It also challenges people to “avoid categorical assumptions of the city” and embrace the “complexities of local contexts and diverse urban residents” (Sheehan 2021, 6). A similar task is enfolded in this paper when the nature of HERRCs and the linguistic patterns of interpretation are taken up in this analysis. HERRCs are designed with a temporary focus in mind, as evidenced by other scholars cited in this paper. But assuming this categorical purpose of the HERRC overrides the way complexities can emerge among “diverse urban residents” that take up new practices of living within their new places of temporary residences. How might we challenge the narrative of the HERRC by positioning language as a social practice of interpretation? That is the central question generated by the nature of this analysis.

Anooradha Siddiqi takes up similar questions about social practices of interpretation in her work studying the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya. She illustrates how different forms of knowing and critiquing the architecture of humanitarianism can emerge when people look closely at the construction of the camp through worldmaking (Siddiqi 2024, 4). This produces a discourse of the architectural environment of the camp where the agency of building and narrating the purpose of the refugee camp is taken up by residents who live there. In the same way, these narratives bring insight into the historical significance of inhabitation: how sites are lived and experienced by the people who spend their lives within them. It permits Siddiqi to undertake a theoretical examination of the Dadaab camp that offers new ways of understanding refugee settlements and the architecture of emergency. Her analysis notes that humanitarian settlements can represent more than zones of rupture and trauma but places with “recoverable architectural historical import” (Siddiqi 2024, 47). These two concepts work in tandem to position HERRC sites as places where similar discursive events transpire. Repurposing hotels for HERRC residential use drives at the notion of a “recoverable architectural historical import” by drawing on an existing structure that can produce a space where worldmaking can occur. What does it mean to “live” for two months in a hotel? That is a central question when HERRCs are analyzed in the same, rigorous and conceptual way drawn from Siddiqi’s conclusions.

Methods of Semi-Fieldwork

This next section of the paper will explain some of the methodologies used to generate the results that exist in conversation with the literature presented in review. This study of language in space uses a sort of fieldwork that I call semi-fieldwork. This acknowledges how this paper relies on practices endemic to the practice of ethnography to construct its findings but also underscores how the nature of these results is not supported by fully-fledged fieldwork. This paper instead uses semi-fieldwork to propose initial findings that might exist in conversation with existing scholarship and therefore pose areas of future inquiry in the subject. Semi-fieldwork in the context of this piece is built as a practice of participant observation that produces evidence and reflection on the use of language in space to describe the environment of the HERRC. Very limited fieldnotes were taken during the two months of fieldwork presented in this paper. They include quick jottings of conversations, events, and exchanges that happened in the HERRC between me and constituents that I worked with in Spanish and Arabic. They detail the types of vocabulary, speech patterns, and behaviors that surfaced throughout my work on site. Some fieldnotes contain references to specific people that are referred to only by first name and last initial (or first name, middle initial, and last initial if first names are repeated). This helps preserve the anonymity and safety of many residents who have immigration and asylum cases pending.

These brief fieldnotes are a snapshot of the types of living and speaking that happen within Candler HERRC and are important to note because of their important implications. Since the methodology of my fieldwork is built around mostly observations of speech, there remains more work to uncover how linguistic pragmatics in Arabic and Spanish might reveal more narratives about spatial temporariness if sustained study continues. Much of this fieldwork relies on my own positionality as a person coming from a family of immigrants and as someone who has spent a considerable amount of time learning Arabic and Spanish to engage in the conversations documented in the following section. However, with limited dialect training in Levantine Arabic, and many constituents who spoke different dialects that I have not studied, made some of this fieldwork challenging to document when Arabic speech varied so much on site. Wherever possible, I leveraged my language expertise to produce the most accurate fieldwork accounts as possible. As more fieldwork continues site, this positionality will undoubtedly expand and complexify as questions of political agency, professionalism, and linguistic fluency are challenged throughout the remainder of my work at MOIA. My work as an intern over two months consistently means that, although in many cases I have the desire to engage more with my constituents, the demands of my position require me to attend to different obligations throughout the week. Though I could include these interactions in my fieldwork—and often do when needed—this paper will solely include reference to my work at Candler HERRC to focus in on the particularities of linguistic pragmatics and spatiality in temporary architecture. To provide the results based on this semi-fieldwork conducted over two months, this brief discussion of positionality is important to acknowledge.

Results

The results section of this paper is divided into two sections. The first explores the specific pragmatics of Arabic and Spanish language in my fieldwork at Candler HERRC. It notes how specific uses of words in context—constituting linguistic pragmatics—attach specific semantic meanings of space to ideas of home and permanence in both Arabic and Spanish registers. The second will explore how these language pragmatics created a new semantic code used to categorize spaces of the HERRC differently than before. This meant that through repeated use of specific words in specific contexts referring to space, the meaning of these places started to mutate throughout my observations. The discussion section will explore more about how these mutations created a new political approach to temporary architecture and identities.

Language Pragmatics and Spatiality

This section centers the study of linguistic pragmatics to understand the nuanced ways that space is articulated and discussed within Candler HERRC. These results are generated from fieldwork that observes certain Arabic and Spanish words being used in context and how the translation of these words produces novel ideas about the spatiality of the HERRC. I begin first by discussing Arabic language pragmatics at Candler HERRC and then shift to Spanish.

Arabic language study is anchored in the understanding that the Arabic language is rich, conversational, and dynamic. It is built on a root system that uses combinations of three letters and ten arrangements—or forms—of these letters to construct thousands of meanings for a single root. This idea is what grounds this fruitful analysis of Arabic language pragmatics at Candler HERRC. With so many ways to deploy the root and form system, speakers can create thousands of unique words that articulate specific, personal, and interesting experiences. The words picked up through fieldwork represent only a small number of words that were repeatedly used to refer to spaces in the HERRC and are documented using their original Arabic spelling and transliteration for the benefit of readers who wish to vocalize these words as they were spoken (Table 1). The word “ghurfa” was one of the most common words used to refer to the individual rooms where residents lived during their stays at Candler HERRC. The word is just one in a long list of words that are used to describe interior spaces; for instance, the word “makaan”—not included in Table 1—simply means “place” or “location” without much precision. But the term “ghurfa” is specific to ideas of house and home. In other contexts, for example when talking about a classroom or other spaces in buildings, the word can be used simply to refer to an enclosed space where people are or reside. But referencing the word, especially in the possessive “ghurati” meaning “my room” assigns the term to mean “my bedroom” through Arabic pragmatics. The specific context of the possessive and the deployment of the term to refer to the individual spaces where HERRC residents slept represents a specific pragmatic choice in the Arabic speech patterns I observed in my fieldwork. It assigns residential spaces in the HERRC not to temporariness, but to permanent ideas of the house and the home where people live and maintain a close and deep personal connection. As I will discuss later, this assignment produces a semantic mutation in linguistic patterns of speech that allow the HERRC to be interpreted as a home rather than temporary shelter (given that residents are only granted sixty days to stay at HERRCs in New York).

Beyond speech referring to interior spaces of the HERRC, other terminology used to refer to the built environment of the HERRC further evidences this pragmatic nuance found in my linguistic fieldwork. Residents, over time, began referring to the HERRC building using the word “beit” which means “house” rather than using the term “binaya” which means building (Table 1). Initially, I used the second term while engaging with residents of the HERRC; but over time I observed more people using the term “beit” and switched my vocabulary to match. In a similar fashion as the term “ghurfa,” the Arabic word “beit” in translation shows how the pragmatic choices residents make while deploying the language connects the HERRC to ideas and sensibilities of house and home. This again affronts the nature of HERRCs as temporary shelters when one considers how residents themselves refer to the site as a “house” rather than simply a “building.” This pragmatic choice underscores the way HERRCs are conceived more as permanent homes rather than temporary environments where people can find momentary shelter over sixty days. Similarly, constituents who saw me multiple times began referring to me as “akhi” and “SadiQi,” began to appear more and more frequently as I returned to the site. These words, meaning “my brother” and “my friend” respectively, connote a sense of familial connection and friendship between people who deploy these terms in direct, interpersonal addresses. While “akhi” and “SadiQi” might literally mean “my brother” and “my friend” when referring to a person who is not in the same room as the speaker, these terms produce a sense of intimacy and connection when used in directed statements. Once again, this pragmatic choice in Arabic linguistic patterns of speech observed in my fieldwork connect the space of the HERRC center to ideas of collegiality, familiarity, and of home. People are not afraid of connecting with people they see multiple times and using terminology to convey appreciation and friendly affection. This idea confronts how HERRCs are temporary shelters for residents who, after sixty days, might not see the same people when they change locations.

This was especially evident when I observed and exchanged the word “ashoufak” (gendered for male addressee) with people who spoke the term first in farewell. The word means “see you” and is specific to the Levantine dialect of spoken Arabic; it also implies a sense of return, in that people who speak the term will see the other person again in the future. This nuance once again provides evidence of how pragmatic choices in Arabic language were deployed to convey familiarity and attachment to other people within the temporary space of the HERRC center. This again confronts the reality that these HERRC spaces are not permanent places for people to live, but sites for people to find footing in New York over only sixty days. The deployment of this term therefore represents a substantial way that residents speak to people within the HERRC with an implied sense of future return, either to see or speak with the other person again. In my Spanish language engagements with constituents living in the HERRC, similar patterns of linguistic pragmatics are evident, but in smaller ways.

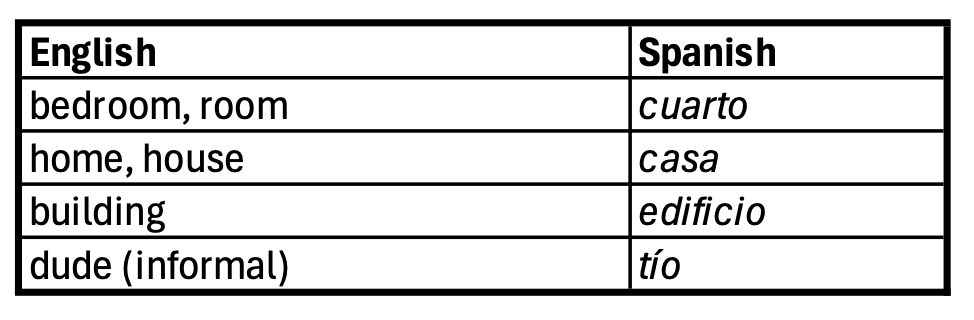

In my work with Spanish-speaking HERRC residents, the interchangeable language used to describe HERRC space is what constituted the unique pragmatic choices documented in my fieldwork (Table 2). Words like “casa” and “edificio”—meaning “house” and “building” respectively—were used about equally often to refer to the physical environment of the HERRC itself. While this is not as deliberate as some of the specific pragmatic choices in my Arabic interactions where words are repeated to construct a useful vocabulary, it represents how the language of home and more neutral words referring to built space can challenge narratives about temporary shelter at the HERRC. Using these two words interchangeably shows how many residents view the constructed space of the HERRC as a “building” and its role as a “house” at the same time. Similarly, words associated with the house and home appear frequently in the use of the word “cuarto” to describe the rooms where HERRC residents sleep. The term is often deployed when referring to spaces in a house and family but evoking similar pragmatic choices in the HERRC aligns the home environment even more so with the atmosphere of the HERRC. This again challenges the narratives of temporary space that people build outside the HERRC when referring to it as solely a shelter environment for a humanitarian purpose.

Similarly, the word “tío” was often used to refer to me and some of my male colleagues at MOIA in a casual, colloquial way. Translated, the word means “uncle” in English, but it also can mean “dude”—a colloquialism used often in male friendships—in the specific cases of these interactions, where the term does not address a family member. This example of “tío” used outside of familial contexts but still while talking casually and in a friendly way helps describe how the HERRC environment became connected to sentiments of family and friendship through Spanish pragmatic choices while speaking the language. Other non-colloquial phrases could well supplant the word “tío,” like “amigo” which directly translates to “friend” (male-gendered addressee). But deploying a Spanish colloquialism that at once invokes sentiments of family but is used beyond that context helps underscore how residents perceive lasting friendship within the HERRC. This emboldens the sense of permanence that individual residents feel within the HERRC—evidenced especially through interpersonal, friendly interactions—that contradicts the temporary status that is applied to these places. Taking these considerations in Arabic and Spanish in mind and the way pragmatic linguistic choices in both registers challenge the temporariness of the HERRC, the next section explores how linguistic pragmatics in both languages create a new semantic code that mutates the purpose of spaces in the HERRC.

Semantics, Space, and Politics

Given these new pragmatic choices within patterns of spoken Arabic and Spanish, this portion of the results proposes that these choices build a new semantic code that mutates spaces of the HERRC. Their spatial and political purpose as a temporary structure is challenged as these pragmatic choices are reflected in the vocabulary of increasingly more HERRC residents. Consequently, the HERRC—in translated speech—becomes a site of permanence and home-building rather than an architecture of emergency or temporariness. Since noting the use of these words and the pragmatic choices that generated their appearance, more residents have begun using similar patterns of speech. I propose that over time, these pragmatic choices constitute a new semantic code that assigns a new literal significance to the spaces of the HERRC. In other words, through repetition and re-articulation of pragmatic nuances in spoken Arabic and Spanish, the HERRC is not just articulated as a sort of permanent home, but it becomes one. The terminology used to refer to elements of the HERRC’s build environment no longer constitutes a series of individual choices in spoken language but rather a larger shift towards their repurposing. Temporary sleeping quarters become bedrooms, acquaintances become brothers, and a hotel becomes a house. With these new designations of space, the HERRC starts to mean something different to the people who live within it. They are not temporary shelters or products of humanitarian emergency architected to help migrants looking for housing in the city. They are houses with family and friends that people will see repeatedly and a bedroom of their own. This does not mean that HERRCs are designed as permanent housing or that they are supposed to be those things; HERRCs still pose a challenge for migrants and refugees who want permanent residency in the city. However, the way HERRC inhabitants describe their space imbues the lived environment of these buildings with a semblance of home. It presents a politics of space not determined by any one definitive policy that New York City uses to govern these HERRCs. Rather, it shows that a politics of belonging is constructed through language that describes and even challenges the purpose of these places.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper analyzes current literature on the architecture of emergency and temporary spaces—such as HERRCs—that influence the politics of belonging for immigrants and migrants seeking residency in the city. At the same time, it identifies how pragmatic choices in spoken Arabic and Spanish create a new semantic code that transforms HERRC centers into sites of belonging and permanence, resembling a home for those living within them. Thus, a new politics of belonging, representation, and familiarity emerges through speech, particularly when this speech is notated and translated into English equivalents. This idea confronts existing narratives about how HERRC centers are designed as temporary spaces and the urgent ways these architected environments are constructed to exclude. Residents in these spaces conceive of their own sense of belonging and permanence through speech pragmatics and discourse. They build a new semantic code in these languages that assign discrete sentiments of home, the house, family, and, therefore, permanence through the repetition and consequent endogeneity of these pragmatic choices. It is unclear whether these linguistic findings observed through fieldwork are intentional; these terms may be wielded purposefully to assign new meaning and structure to the temporary spaces of the HERRC. But the nature of this fieldwork and the spontaneous observations of these pragmatic choices suggest that this new semantic code and its political implications are more gradual—even serendipitous—rather than planned or organized. The findings of this paper assert, perhaps the grain of existent scholarship, that ways of speaking and perceiving temporary architecture allow people to endow a sense of ex-citizenship—an identity beyond citizenship—to their asylum-seeker, migrant, or immigrant identities. In other words, the invocations addressed in this fieldwork suppose that spoken language can recast the role of people within HERRC spaces increasingly as residents rather than foreigners in the paradigm of Di Cesare’s “resident-foreigner” concept brought up earlier.

The implications of these findings are many, but for the sake of brevity, I offer that the significance of this paper lies in what comes next for the study of temporary spaces and linguistic nuance therein. A more comprehensive study of sentences, exclamations, and other parts of speech might shed more light on how this new semantic code might advocate more strongly for identities of permanence on the heels of a new, volatile federal administration. With such a vehement anti-immigration stance, new terminologies and ways of speaking might emerge over the next several months within HERRCs and other spaces that more heartedly transform the identity of inhabitants into urban residents than temporary foreigners in a new place. The camp might become more of a home, house, and place of permanence when we continue to study how language is deployed to study space. For other scholars working to study the spatiality of language—or how language refers and responds to space—similar studies in other environments might show how people auto-categorize themselves into non-normative categories that confront social labels. In short, to better understand how immigrants and new arrivals to the city grapple and recast their identity, perhaps we need only listen.

References

Abourahme, Nasser. 2020. “The Camp.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 40 (1): 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201X-8186016.

Caldeira, Teresa PR. 2017. “Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, Transversal Logics, and Politics in Cities of the Global South.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479.

Di Cesare, Donatella, and David Broder. 2020. Resident Foreigners: A Philosophy of Migration. English edition. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity.

Gowen, Amy, ed. 2021. Rights of Way: The Body as Witness in Public Space. Onomatopee 195. Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

Herscher, Andrew, Nikolaus Hirsch, Markus Miessen, and Omer Fast. 2017. Displacements: Architecture and Refugee. Critical Spatial Practice 9. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Kreichauf, René. 2019. “From Forced Migration to Forced Arrival: The Campization of Refugee Accommodation in European Cities.” In Arrival Infrastructures: Migration and Urban Social Mobilities, edited by Bruno Meeus, Karel Arnaut, and Bas van Heur, 249–79. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_11.

Lozanovska, Mirjana. 2015. “Ethnically Differentiated Architecture in a Global World.” In Ethno-Architecture and the Politics of Migration. Routledge.

Meeus, Bruno, Bas van Heur, and Karel Arnaut. 2019. “Migration and the Infrastructural Politics of Urban Arrival.” In Arrival Infrastructures: Migration and Urban Social Mobilities, edited by Bruno Meeus, Karel Arnaut, and Bas van Heur, 1–32. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_1.

Pérez, Miguel, and Cristóbal Palma. 2021. “Peripheral Citizenship: Autoconstruction and Migration in Santiago, Chile.” In Emergent Spaces: Change and Innovation in Small Urban Spaces, edited by Petra Kuppinger, 25–46. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84379-3_2.

Sheehan, Megan. 2021. “Practice, Perception, and the Plaza: Situating Migration in Santiago, Chile.” In Emergent Spaces: Change and Innovation in Small Urban Spaces, edited by Petra Kuppinger, 63–84. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84379-3_4.

Siddiqi, Anooradha Iyer. 2024. Architecture of Migration: The Dadaab Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Settlement. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478027379.

Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2010. City Life from Jakarta to Dakar: Movements at the Crossroads. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203892497.

Targeted News Service. 2023. “New York Immigration Coalition: Immigrant Advocates Denounce Opening New HERRCs, Call on Adams to Invest in Housing Vouchers.” Targeted News Service, July 13, 2023. 2836236414. ProQuest Central. http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/new-york-immigration-coalition-immigrant/docview/2836236414/se-2?accountid=10226.

Thorshaug, Ragne Øwre. 2019. “Arrival In-Between: Analyzing the Lived Experiences of Different Forms of Accommodation for Asylum Seekers in Norway.” In Arrival Infrastructures: Migration and Urban Social Mobilities, edited by Bruno Meeus, Karel Arnaut, and Bas van Heur, 207–27. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_9.