The Impact of Patronage on Architectural spaces

Patronage shapes the meaning and experience of an architectural space by prescribing size, shape, and content to enforce personal values of the patrons of Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Isfahan, and St Peter’s Square, Rome.

The role of patrons is essential to analyzing architectural spaces and their experiences, particularly in understanding how human presence, movement, and interaction shape, but also, are shaped by the space. This involves examining not only the functional aspects of the environment but also the sensory, emotional, and psychological responses it evokes. Architectural space is traditionally associated with the interior of buildings but it also encapsulates the open area between built structural elements. In other words, the boundaries of space—walls, columns, buildings, and gardens—comprise the experiences of architectural space as much as the practical design components of buildings themselves. The experience of a space is contained within the boundaries of this architectural space. Consequently, this essay will focus on two patrons, Shah Abbas of Isfahan and Pope Alexander VII of Rome, and their commissions of Naqsh-e Jahan and St. Peter's Square, respectively. I argue that patronage shapes the meaning and experience of an architectural space by prescribing size, shape, and content to enforce personal values of the patrons of Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Isfahan, and St Peter’s Square, Rome. This essay will first analyze the context surrounding Naqsh-e Jahan Square and St Peter’s Square and their patrons, with an emphasis on personal values and positions of power. Next, it will visually and spatially analyze each square, focusing on how these spaces reinforce the patrons’ desires for power and emphasis of their values.

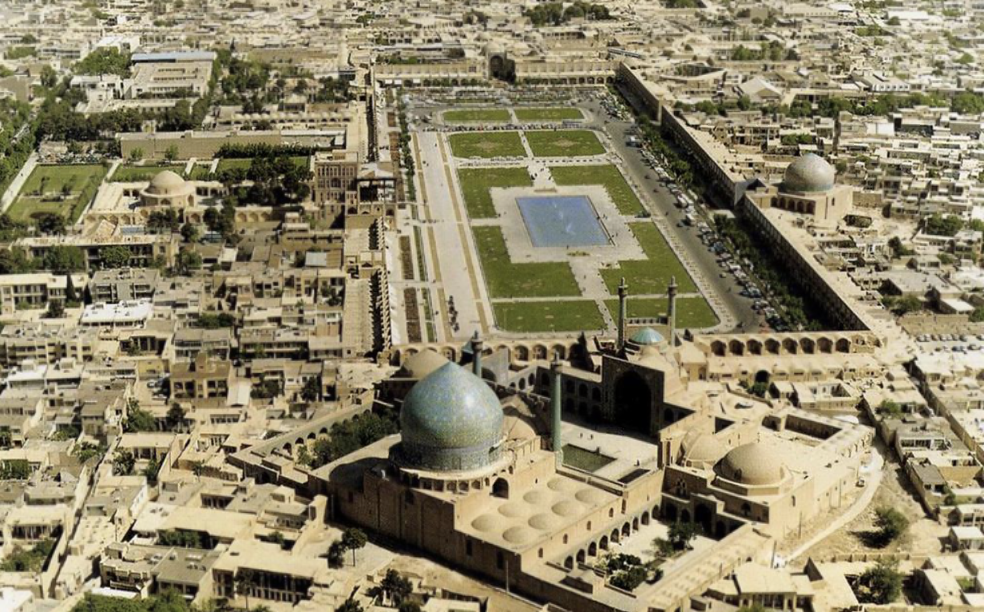

Shah Abbas, the fifth Shah of Safavid Iran, inherited a broken Isfahan with an impoverished economy and an unreliable military. In the late 16th century Isfahan underwent an urban renewal. The city became the focal point of Shi’ism, which emphasized political and sociocultural centralization. Shah Abbas, patron of Naqsh-e Jahan square, carried these ideals into his requirements for the commissions of architectural spaces in Isfahan.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, Isfahan was a hub for urban life, culture, and architecture. It boasted new architectural spaces such as mosques, markets, gardens, and squares (Babaie and Kafescioğlu 2017, 847). One notable space is Naqsh-e Jahan square, its gardens, and connecting pathways to the Zaindeh River, designed by Mohammad Reza Isfahani and Ali Akbar Isfani. The expansion of architecture in Safavid Isfahan and in accordance with Shi’ite kingship practices is emblematic of the patronage that influenced the underlying purpose and larger significance of Naqsh-e Jahan square.

Patronage not only impacted Safavid Isfahan, but also mid-17th century Rome. The restoration of St. Peter's Basilica and Square by Michelangelo, later modified by contributions from Maderno and Bernini, was a fundamental restoration to the post-reformation Roman Catholic Church. The patron of the restoration, Pope Alexander VII, wished to replan Rome and break the labyrinth created by the medieval streets. His papacy focused on urban planning that tried to easily link basilicas, piazzas, and other significant religious buildings for pilgrimages. An easily manoeuvrable city would entice and increase the number of pilgrimages to the capital, unifying like-minded individuals into a concentrated sociocultural and religious atmosphere.

The Roman Piazza is an essential part of the architectural composition of the city. The key elements include colonnades and buildings surrounding an open square, sometimes adorned with sculpture. The colonnades and buildings surrounding a piazza facilitated both private and public activities such as commerce, government, and ritual spectacles. The inherent characteristics of a piazza create a natural space for gathering and unifying a group, like pilgrims within the city. Consequently, Pope Alexander VII, chose to include a piazza in front of the Basilica to fulfil the objective of concentration of religious power. Shah Abbas and Pope Alexander VII illustrated their political and religious intentions of centralization through urban renewal and their commissions of public squares. This shows that patrons shape the meaning of architectural space by highlighting personal values through the built environment.

In addition to the meaning behind patronage of architectural spaces, it is important to understand the experience of city-goers in those spaces which is influenced by visual and spatial decomposition; the process by which a large urban area is broken down into manageable, human-scaled spaces. I will first analyse Naqsh-e Jahan Square then proceed to St Peter’s Square. Located in the south-east of the old city, Naqsh-e Jahan square consists of a large, elongated rectangle. Along the edges, there is a continuous double order of piers, adorned with polychrome glazed tiles, pathways, and a four-part garden in the centre, a charbagh. The long facades are broken by grand entrance ways to the Shah Mosque on the south, the mosque of Shaykh Lutfallah on the east, the bazaar on the north, and the ‛Ali Qapu Palace to the west. Government, religion, and the monarchy are condensed into one central space, and therefore people with many objectives are obligated to gather in one location. Moreover, the style of square was replicated across the empire; the Ganji-I Ali Khan complex in Kerman is evidence of this repeated motif that centered multipurpose rather than single-use space. The repetition of architectural spaces in conjunction with the gathering of people serves to illustrate the patrons desire for a centralized gathering space in each major city across the empire to facilitate political and socio-cultural activities.

Pope Alexander VII had three requirements for St. Peter's square that he relayed to its designers and planners. Bernini had to include a gathering space for blessings from the Benediction Loggia, a secondary gathering space for Sunday blessings from the window of the Vatican Palace, and a grand approach to the Basilica to prioritize the importance of the primary church of Christendom. These requirements convey the patrons desires and emphasize his values of gathering and welcoming congregations to the piazza. The space is framed and defined by two, curved, free standing colonnades with four rows of Doric columns creating three separate passageways. The colonnades are crowned by a balustrade and sculptures.These elements form the image of arms welcoming the congregation into the piazza and the church. The low and heavy profile of the colonnade arms emphasize Maderno’s light and vertical basilica façade by utilizing Corinthian columns and travertine stone (Preimesberger and Mezzatesta 2003). The contrast between light and heavy, bright and dark further highlights the desire of the patron to create a space for gathering and containment around a central area.

Furthermore, both St. Peters and Nash-e Jahan are positive spaces because they are ideal for lingering and gathering. This is key in designing architectural open spaces for centralization and social interaction per the desires of both patrons. Each square is surrounded by roads, which are considered negative spaces, or spaces that promote movement rather than dwelling. Thus, the negative spaces surrounding each square guide people into the positive spaces intended for stagnation and socialization. This is how patrons and designers shape the experience of an architectural space. These examples illustrate how patronage impacts the experience of an architectural space by prescribing shape and content; at the same time, these patronage-influenced spaces guide urbanites to linger and stresses centralization of sociocultural, religious, and political power in the process.

In conclusion, this essay contends that patronage plays a significant role in shaping the architectural meaning and experience of a space by imposing specific content and characteristics that reflect the patrons’ values. This is exemplified through a contextual and spatial analysis of Nasqh-e Jahan and St. Peter's square. Through these examples three key points can be concluded. First, patrons have strong values and objectives with their commissions to propagate their ideals through architectural expression. This deliberate shaping of physical environments reflects their aspirations for societal influence and legacy. Secondly, architectural spaces impact the movement and stationariness of people. The layout and design choices dictate how individuals navigate and interact within these spaces, thereby influencing social dynamics and communal behaviors. Lastly, the movement, or lack thereof, of people affects the political and sociocultural aspects of a society in accordance with the patron’s objectives. By controlling the flow of people, patrons can subtly or overtly influence societal hierarchies, ideological adherence, and collective identity. In essence, the architectural legacy of patrons such as those behind Naqsh-e Jahan and St. Peter's Square exemplifies how patronage extends beyond mere construction, becoming a vehicle for the projection and preservation of values, ideologies, and societal norms across generations.

References

Reza Isfahani, Mohammad, and Ali Akbar Isfani. 1598. Naqsh-e Jahan Square. Isfahan.

Atkinson, Niall. 2013. "The Italian Piazza From Gothic Footnote to Baroque Theater." In A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, 561-581. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Babaie, Sussan, and Çiğdem Kafescioğlu . 2017. "Imperial Designs and Urban Experiences in the Early Modern Era." In A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, 846-873. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Bernini, Gian Lorenzo. 1656. St Peter's Square. Rome.

Dale, Stephen F. 2010. "Empires and Emporia: Palace, Mosque, Market, and Tomb in Istanbul, Isfahan, Agra, and Delhi." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53 212-219.

Frederick, Matthew. 2007. 101 Things I Learned in Architecture School. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: The MIT Press.

Galdieri, Eugenio . 2003. "Royal Maidan." Grove Art Online.

Oxford Reference. 2009. The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Preimesberger, Rudolf , and Michael Mezzatesta. 2003. "Bernini, Gianlorenzo." Grove Art Online .