Public Art and Murals in Washington, DC’s Gayborhoods: Exploring Urban LGBTQ Placemaking in the Nation’s Capital

This study mobilizes deep mapping and GIS spatialization research to investigate how public art and open-space murals are embedded within Washington, DC’s urban landscape. Indexing these public arts allows a more compressive understanding of these vibrant enclaves of the nation’s capital.

Abstract

Washington, DC has some of the most vibrant gay neighborhoods in the United States. Over time, the percentage of LGBTQ+ residents in the city has grown to become a significant portion of the population. Neighborhoods like Adams Morgan, Dupont Circle, U-Street, Mount Pleasant, and Columbia Heights retain a large majority of LGBTQ+-identifying residents and have become central “gayborhoods” within Washington, DC. While these areas of the city maintain rich gay nightlife and culture, an important bedrock of these communities is both the public art and active LGTBQ+ placemaking that classify these areas of the city as “gayborhoods.” This study mobilizes deep mapping and GIS spatialization research to investigate how public art and open-space murals are embedded within Washington, DC’s urban landscape. Indexing the nature of these public arts—their content and character—allows a more compressive understanding of the shifting culture and politics of these vibrant enclaves of the nation’s capital. Using a database of 265 images mapped across approximately five of DC’s “gayborhoods,” this study reveals how informal and non-commissioned public “murals” comprise most of the open art within these neighborhoods. Further, the more neutral, often abstract, content of these “murals” highlight the diminishing impact of LGBTQ+-centered content in placemaking practices within DC’s “gayborhoods.” Thus, this study shows how the contemporary motifs within public arts reflect common themes pertaining to DC’s multicultural identity and history rather than LGBTQ+-specific narratives. Public murals and arts therefore become a way for the city’s gayborhoods to promote diversity and multiculturalism rather than to establish strictly LGBTQ-specific space. This study invites further exploration of how public art and the politics of placemaking manifest within the DC’s urban landscape.

Introduction

The introduction of this manuscript is divided into four sections. The first will discuss urban queer identities and how the spatiality of these identities has changed over time due to various factors. The second will discuss the early LGBTQ histories of Washington, DC with an attention to how placemaking operated to combat the criminalization of LGBTQ identities in the city. The third will investigate the disappearance of urban gayborhoods while providing insights into how these areas are recouping their standing as gay enclaves. Finally, the introduction will include a section about DC’s gayborhoods and placemaking efforts taking place within them.

Urban Queer Identities

Urban queer identities exist in constant conversation with other urban phenomena, like gentrification and urban flight. In many instances, these processes erode the majority-LGBTQ population in urban areas and the identity of these places as queer enclaves. This portion of the introduction will begin by addressing the economic factors that have precipitated the decline of urban gayborhoods during the 20th and 21st centuries. Then, it will address the social vectors that have motivated the decline of these gayborhoods. Finally, this section turns to address the question of Washington, DC’s specific queer geographies. Petra Doan explores the disappearance of queer neighborhoods and spaces in the city through economic trends. Gay businesses, bars, and other outlets have existed for a long time, but their patterns of use have changed in response to crackdowns on LGBTQ identities. Riots at places like the Compton Cafeteria in San Francisco and Stonewall Inn in New York created a more liberalist activism movement that enabled more distinct LGBTQ venues to emerge that catered explicitly to these populations. But in the 20th century, these spaces became subject to gentrification (Doan 2015). This gentrification led to the “de-gaying” of these spaces and might provide a model for other “queer spaces” (Doan 2015, 4).

Alan Collins provides a possible reason for this gentrification by studying the Soho neighborhood in London. Urban decline in some neighborhoods leads to the development of gay venues and businesses in that region, which attract LGBTQ clientele. This increases profits and brings in more venues for an increasingly queer-dominated urban area; over time, these formerly run-down areas bounce back from decline. Demand for property in these areas increases and brings more heterosexual residents, reducing the queer majority in these regions. As prices continue to rise, the decline of gay-dominated spaces is accelerated by gentrification as LGBTQ residents lose their majority and move away due to high living costs (Collins 2004). However, Collin’s hypothesis is also challenged by Doan and Higgins who explore the Peachtree Street neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia (Doan and Higgins 2011). They find that municipal promotional efforts within the area simulated redevelopment and persistent neglect of gay areas of the city in Midtown. This forced the historical gay neighborhoods of Midtown to the periphery of the city, reducing the dominance of queer spaces in the larger Atlanta area (Doan and Higgins 2011). Doan, Collins, and Higgins provide compelling evidence to explore the disappearance of gay neighborhoods in the city and begin to problematize some of the main points of departure in this study.

Amin Ghaziani builds on this research by providing a socially minded analysis of why gayborhoods in the city are disappearing over time, arguing that changing social conventions throughout the nation are to blame. This precipitated an expansion mechanism that effectively grew and altered the boundaries of gayborhoods around the US (Ghaziani 2014). Earlier, gayborhoods were critical places where criminalized identities could seek refuge in a post-World War II social world. But as acceptance and tolerance of LGBTQ identities increased over time, the “safe” streets that have delineated gay neighborhoods in urban areas gradually dissolved as other spaces become associated with acceptance and tolerance (Ghaziani 2014). Thus, gayborhoods evolved alongside the changing political and social attitudes towards LGBTQ identities throughout the US. Gayborhoods declined because the sanctuary they provided for LGBTQ people spread elsewhere. Ghaziani qualifies this by asserting that LGBTQ, minority groups moving out of gayborhoods will still group together. Homophily—or the tendency for minority groups to stay together—coupled with the migration of LGBTQ folks within cities has created smaller gayborhoods within urban areas. In other words, when homes become too expensive or neighborhoods become too straight, LGBTQ people will move together to new places and establish new gayborhoods away from their original homes (Ghaziani 2014). These minority groups want to be together and although they are able to blend-in with the larger multicultural diversity of urban areas, queer geographies are still influencing our cities. Thus, the disappearance of gayborhoods might be better explained not as a linear movement towards obscurity, but as an evolution towards a result drastically different from earlier paradigms of the “gayborhood” itself. This is evident within the unique queer histories and geographies in Washington, DC.

Early Histories of LGBTQ Washington, DC

This portion of the introduction pays special attention to the queer histories and geographies of Washington, DC. It begins first with a broader overview of DC’s queer history then focuses on critical neighborhoods in the city essential to this history. Finally, it will synthesize the literature presented and transition to focus on the unique landscape of DC’s queer geographies and enclaves more recently.

The importance of selecting Washington, DC as a site to study queer geographies cannot be understated. DC is, by all purposes, a queer capital city, where policy influencing the lives of LGBTQ Americans developed alongside gay experiences in DC. Genny Beemyn writes that “while Washington has received considerable attention as a national stage for LGBT rights battles, it has rarely been examined as either a queer capital or a queer capital” (Beemyn 2014, 1). This qualifies the importance of studying Washington, DC now as both a political and queer city; its urban landscape enacts and informs the way gay lives are lived in the United States. The confluence of political influence and LGBTQ narratives in a single city makes DC a particularly important place to investigate LGBTQ life, space, and placemaking (Beemyn 2014). Thus, this study identifies DC’s unique position as a queer capital city to explore how queer and politicized identities are superimposed within the city’s urban geography. Diving further into this geography requires an appreciation of DC’s early history. The storied 200-year history of DC’s LGBTQ residents begins with its planning. While the foundations of the city were laid, the design the city became increasingly spread out by Pierre L’Enfant, a so-called “affected” man, a term that implies homosexuality during the late 19th century (Muzzy 2005, 1). The level of intimacy among homosexual residents of the city involves a certain amount of speculation, but the history of homoaffection in the city was well documented within the city. The city grew with several gay and lesbian influences both told explicitly and through more circumstantial historical evidence. Homosexual partnerships were referred to as “special friendships” during the initial history of DC’s LGBTQ spaces (Muzzy 2005, 1). Many of these friendships were not hidden from the public but concealed to remove some of the widespread political ramifications of homosexuality during the early history of DC. From Alexander Hamilton to President Abraham Lincoln, the LGBTQ and political histories of Washington DC have overlapped in unexpected ways (Muzzy 2005, 1). Muzzy highlights this by mentioning that “the end of the century brought to light one of the most delightful revelations of the Washington social season when President Cleveland entertained an Indian princess of questionable gender” (Muzzy 2005, 1). The new century in Washington’s history was rampant with hidden histories of LGBTQ interaction and intimacy in the city. Social clubs from the 1800’s eventually transformed into the bar scenes of the 1900s. In the 1920s, same-sex dancing was a backroom affair; but nonetheless, gay arts emerged through theatre productions in the city. Thus, DC’s burgeoning gay residents, arts, and identity began to accelerate; other scholars provide alternative lenses to view this development into the 21st century.

(Disappearing) Queer Geographies of Washington, DC

This next segment of the introduction focuses heavily on the well-known, but changing, queer geographies and neighborhoods in Washington, DC. First, this section will explore the decline of gayborhoods like Dupont Circle in DC’s history. Then it will turn to the rise of other smaller pockets of LGBTQ urban space in Washington, DC that emerged over time. Finally, it will conclude with an attention to these new multicultural LGBTQ spaces and placemaking efforts that are trying to recoup the status of gayborhoods in DC. Early in the 1930s, Dupont Circle was widely known as an important gayborhood in the city; but its reputation as a gay enclave in DC only briefly flourished in the years immediately following the war. In the 1970s, gay political movements began to grow throughout the region, building on the momentum of the Stonewall riots in New York (Greene 2015). In the mid-1970s, the neighborhood gained of its reputation as a gayborhood in Washington DC when numerous LGBTQ institutions emerged to “mobilize and foster a visible and cultural community” (Greene 2024b, 63). But this did not eliminate future challenges for the neighborhood. In the late 1970s, Dupont Circle experienced rapid gentrification; straight and gay professionals began to move into the area and reinvest in properties (Greene 2024b). The 1980s, therefore, brought steep increases in rents, well into the “four-digit range, pricing out and displacing many LGBTQ residents” (Greene 2024b, 64). These soaring prices forced many gays and lesbians out of Dupont Circle and they found housing opportunities in adjacent neighborhoods.

Nathaniel Lewis also explores decline of Dupont Circle as an urban gay space due to the “diffusion of queer residents and businesses” into other neighborhoods (Lewis 2015a, 58). These transformations impacted the “cohesion, sustainability, and futurity” of the queer communities in DC (Lewis 2015a, 66). For example, less visible queer geographies in the city have the tendency to compromise the safety of the queer population and the ability for social support networks to uplift new arrivals in these communities. This means that the boundaries of historically clear-cut gayborhoods in the city vanished as the integrity of these safe spaces reduced over time. Individual attitudes of LGBTQ residents—primarily among gay men—also influence similar patterns of gayborhood disappearance. Though gay men might enter cities to explore new life trajectories, they are forced into a system of local economy that prioritizes “individual and competitive modes of consumption” (Lewis 2017, 708). This puts strain on LGBTQ residents to seek out patterns of social behavior (often normalized within concentrated gay communities) that disagree with their accepted desires of everyday life. LGBTQ residents are leaving these concentrated gayborhoods like Dupont Circle and into gentrifying neighborhoods like Shaw, Fort Totten, and Navy Yard (Lewis 2017).

This dispersal is also deeply influenced by DC’s history of racial discrimination and segregation. Dupont Circle attracted many of Washington’s Black Elite and upper-class residents who settled in the “northeast portion of Dupont Circle called Strivers’ Section” (Greene 2024b, 62). The separation of racial groups was ongoing and endemic within the history of these gay enclaves in Washington, DC. As gay residents moved out of Dupont Circle, the racialized geographies of urban life within the city began to take shape through the new places where these residents moved. LGBTQ residents of color found more opportunities in the historically African American neighborhood of Shaw. The nearby U-Street neighborhood—positioned close to Howard University—anchored Shaw in a rich history of Black intellectual and cultural nuance that rivaled New York’s Harlem renaissance. As Shaw grew in popularity, 14th Street and Logan Circle gradually became the dividing line between the white, Victorian homes of Dupont Circle and the African American communities who lived and worked in the Shaw area (Greene 2015).

For decades since, Shaw, Adams Morgan, and Columbia Heights have remained a home for minority queer communities who made space in the city for businesses to support the unique needs of their community. In the 1990s, the number of gay Latino bars emerged to support DC’s growing population of LGBTQ Hispanic folks. Casa Ruby and the GLBT History Project also emerged to support the burgeoning history of LGBTQ Hispanic residents in Washington, DC (Greene 2015). Through this examination of DC’s changing gayborhoods, the “local difference” within “the broad landscape of shifting gay sexualities and spatialities” within the city is evident (Lewis 2017, 709). But these transformations do not always signal an inclusive future for DC’s gay communities (Lewis 2015b, 73). These transitions in urban life are produced by changing social norms, behaviors, and desires that redraw divisions with the queer population. They further separate the LGBTQ urban community of Washington, DC. Dupont Circle is a primary example of this. But this does not mean that residents have accepted this trajectory of gayborhood decline.

Residents in the neighborhood have tried to re-establish Dupont Circle’s identity as a designated LGBTQ space using spatial activation and placemaking. Moreover, the disparate urban enclaves of gay live in Washington, DC mobilize similar practices to concretize the gay identities of these LGBTQ spaces. Logan Circle and Shaw began to grow as new gayborhoods in the city. This dispersion of LGBTQ residents in the city spelled out a new attitude in the city: gay and lesbian identities became increasingly accepted in non-LGBTQ-dominated areas of DC. LGBTQ residents could live freely and openly outside the gayborhoods that previously anchored them in a community of accepting and welcoming peers (Greene 2024b). The next section of this introduction explores contemporary practices in urban placemaking to understand how ideas about the disappearing gayborhood might be challenged today.

From Dupont to AdMo: DC’s Gayborhoods, Queer Enclaves, and Placemaking

This section introduces more specific questions and theories about LGBTQ placemaking in Washington, DC’s gay enclaves and neighborhoods. It explores early histories of gay placemaking and living in DC while underscoring race, economic stratification, and gentrification within these questions of gay life in the city. Finally, it will turn to more fine-tuned forms of LGBTQ placemaking research by addressing how ethnographies of urban nightlife can index changing queer identities in the city. To begin, Theodore Greene uses Lafayette Square in Washington, DC to explore the history of gay placemaking in Washington, DC. He points to how the square was used in the early twentieth century to help LGBTQ people meet one another when gay relationships were prohibited (Greene 2024b). Lafayette Square became a place where friendships, relationships, and romance could flourish beyond the traditional spaces where homosexuality was criminalized and harshly judged. This first instance of gay placemaking allowed Lafayette Square to emerge as a distinct LGBTQ space. But other areas in the city, exhibit this phenomenon as well. Greene further emphasizes that although LGBTQ residents come from different places within the city, there is still a common tendency for gay residents to independently show ownership and care over LGBTQ places within the city.

These residents assert their ownership of places as gay spaces through something called “place reactivation,” or the “temporary revival of inactive place cultures within a space, neighborhood, or locality” (Greene 2024a, 8). People can revitalize spaces as necessary to mobilize their own desires and wishes for what that space should be. Place reactivation exposes the “fleeting, shifting nature of places” despite the fixed quality of space itself (Greene 2024a, 8). These places within a community can shift from one moment to the next depending on who inhabits the spaces in which these sites are situated. Nightlife is a compelling example of place reactivation at work. By claiming ownership of nightlife spaces and developing “momentary bursts of placemaking,” LGBTQ subcultures can draw “attention to the resiliency of and endurance of place” (Greene 2022, 158). Places can, over time, endure a loss of space, but they cannot endure losing the people and subcultures that grow to inhabit these places through tradition and LGBTQ-based community building (Greene 2022).

Greggor Mattson dives more deeply into this practice in DC, exploring the how Dacha beer garden, a non-gay bar, boasts a large populations of LGBTQ patrons. Mattson interviews the owner of the bar who articulates that a beer garden cannot also be a gay beer garden; for him, the two ideas are in stark opposition to one another (Mattson 2023). But, the owner says, you can have a beer that caters to many different people from all walks of life; Hispanic, LGBTQ, straight, white, and black residents of the city can find a foothold at the beer garden in equal ways. Located in Logan Circle—one of DC’s newer gayborhoods—, LGBTQ placemaking at Dacha beer garden is achieved by its surrounding community. Dacha beer garden is overshadowed by a massive LGBTQ mural of AIDS activist and icon Elizabeth Taylor. The decorations at the bar, tank tops worn by staff, and local fundraisers at Dacha catered to a clearly LGBTQ-oriented population. Events supporting the HIV/AIDS clinic, LGBTQ Victory Fund, and Gays Against Guns used Dacha as a springboard to launch fundraising campaigns in the city (Mattson 2023). Dacha beer garden shows that non-gay oriented spaces can maintain a rich connection to the LGBTQ community through placemaking and the deliberate choice of residents to frequent, host events, and create artwork in these spaces.

As LGBTQ spaces in the city fluctuate, local community members and nonresidential stakeholders use neighborhood participation to translate their attachment and ownership to the space. This process is what Greene deems “vicarious citizenship.” These vicarious citizens can exert power over an area by “appropriating its space and reproducing its meaning” (Greene 2024a, 9). Vicarious citizens can push back against trends of gayborhood disappearance by mobilizing spatial practices to preserve their community identity. These forms of spatial practices are self-enfranchising and allow local resident to protect their vision of community from “heteronormative and homonormative assimilation” (Greene 2024a, 9).

Methods

The methods section of this manuscript is divided into three sections. The first will introduce literature and previous scholarship about the mapping and ethnographic techniques used in this study. It will bridge the two methodologies together to substantiate the combined approach of this study: to investigate queer space through mapping and visual discourse. The second section will consider the positionality of the researcher in relation to the study subject matter and geography. The final section will explain the detailed methodology used in this study to build the map and image dataset used in this study.

Literature and Previous Scholarship

This section of the paper will address existing literature about Geographic Information System (GIS) software and how it has been used over time for various research purposes. It begins with an overview of critical and positivist GIS methodologies and then turns to the practice of ethnography. Since this study uses both visual ethnography and GIS methods, this portion of the paper will address both methodologies, especially visual ethnography. This practice—within the larger domain of visual anthropology—carries critical considerations when combined with GIS techniques. As such, bridging theories and practices in GIS and ethnographic techniques is critical for the scope of this study. Finally, this section concludes by considering similar studies and addressing the unique implications of this manuscript in the larger field of urban studies and sexuality studies.

To begin, Wen Lin introduces the idea of critical GIS by tracking the history of the practice from its roots in positivism. The idea of Critical GIS emerged in the early 1900s as a response to critiques of GIS by geographic researchers. These critiques questioned the positivist epistemology, and the reinforcement of inequalities associated with GIS, including critiques of GIS data’s lack of detail inherent to the technology. It also encompassed critiques of GIS as a positivist methodology, or a technique associated with “universal law-making” through cartographic techniques (Lin 2023). Critical GIS thus emerges a practice for interdisciplinary investigations—including digital humanities and digital geographies—to explore spatial relationships and democratize decision-making processes. In exigent literature about Critical GIS, the practice relies on maps to explore subjective experiences and interactions while motivating researchers to be reflexive and modest in their approach (Lin 2023).

Rupa Pillai puts some of these ideas into practice by discussing the use of GIS mapping to track Jhandis in Little Guyana. Jhandis are small flags that are placed outside homes to let others know what religious ceremonies have taken place there. Despite her work documenting Jhandis which allowed her to more accurately map locations of Guyanese, Indo-Caribbean, and Hindu individuals, Pillai is emphatic about the ethical implications of her work. Her work created ethical dilemmas as vandalism and hate-based criminal activity increased following her research (Pillai 2020). Pillai, therefore, offers a valuable consideration of the ethical implications of GIS mapping projects, both in terms of what the research hopes to achieve and how these projects make information available to the public (Pillai 2020). Consequently, this study will enfold ethical considerations of data presentation and availability.

The bridge between Critical GIS and visual ethnography lies within the practice of Deep Mapping. Les Roberts explains how deep mapping is, “cartography as art rather than science” or a practice driven by “an inclination ‘to conclude with everything rather than to begin from it’” (Roberts 2023, 616). It involves a creative process of mapping, of deeply investigating human experiences, and of placing these practices on everyday space. Deep Mapping using GIS emerges to tell rich spatial stories derived from “experiential as well as objective space” that are ignored by conventional mapping methods (Roberts 2023, 620). Thus, Deep Mapping is a visual ethnographic practice that involves capturing, visualizing, and living the spaces of the world (Roberts 2023, 621). This study employs the use of deep mapping to do this exact thing: understand lived geographies in spaces in Washington, DC’s complex urban environment and understand how LGBTQ identities are mapped on these spaces. This research also combines visual-photographic ethnography methods to make this use of deep mapping more effective.

Erkan Ali explains the philosophical underpinnings of photography as a dynamic practice that tells stories and conveys experiences for artist and researcher alike (Ali 2018, 19). Douglas Harper agrees, who categorizes photography “visual inventories of social life” with ethnographic implications in sociology and anthropology (Harper 2002). In visual practices of sociological ethnography, the practice of photography becomes an effective means of participant observation and a way of documenting relationships with these participants (Becker 1974). Anthropological ethnography that uses photography is mainly leveraged to provide visual evidence of phenomena or affirm the validity of research findings. The main separation between these practices of photography is described more elegantly using reflexivity as the dividing line between the two:

“Whereas anthropology has utilized the power of photography for its [sic] graphic virtues, sociology ‘has tended towards the analytical and explanatory,’ mainly because of a preoccupation with reflexivity in relation to the photograph as a document. It follows from this that pretty much any photograph can hold sociological significance” (Ali 2018; Ball and Smith, n.d.).

Using photographs as data—rather than proof—allows sociologists to inject elements of analytical framing into their photo-driven research. It allows photography and ethnography to work together to explore visual materials and the institutional issues embedded within unfamiliar segments of a familiar research landscape (Ali 2018). This paper strives to do the same by using sexuality, geography, and visual culture as analytical tools to investigate urban placemaking. Furthermore, photographic ethnography is both as a way of documenting the subject of a research project and as a potential way of bridging fieldwork with theory (Pink 2024a). Photographic and visual ethnography can add value to research by constructing “continuities between the visual culture of an academic discipline and the subjects or collaborators in the research” (Pink 2024a, 3). Consequently, ethnographies can create representations that refer to local visual cultures while applying them to academic disciplines on which their research draws. However, gender politics and power hierarchies weigh heavily on ethnographic techniques. The practice of reflexivity, or the way ethnographers relate to their own research can help resolve some of these tensions.

A reflexive approach “recognizes the centrality of the subjectivity of the researcher to the production and representation of ethnographic knowledge” (Pink 2024b, 4). It goes beyond considering a researcher’s bias and strives to critique how social realities are distorted through the research process. This highlights the central importance that the researcher must acknowledge and disclose their personal subjectivities when they tackle their ethnographic subject matter. Consider gendered ethnographies. The gender binary challenges the way ethnography is conducted because the way men and women “experience themselves and their lives is never truly defined,” especially for non-binary gender groups (Pink 2024b, 6). The way researchers and subjects experience “experience themselves and one another as gendered individuals will depend on the specific negotiation into which they enter” (Pink 2024b, 6). Therefore, the question of reflexivity in the context of visual ethnography will weigh heavily on the scope and findings of this research study.

Positionality

Due to the ethnographic and GIS-backed methodologies of this study, it is critical to address researcher positionality to situate its findings in both the academic and social realms of research. There were several factors that made this study easy to conduct. First, by background as a long-time DC resident allowed me to navigate the landscape of my fieldwork with ease. I knew the location and walking routes from my house to reach the gayborhoods I studied. Second, many of these communities boast a linguistically rich and multicultural atmosphere (Modan 2007). My background growing up and speaking Spanish in school allowed me to navigate the bilingual communities in which my fieldwork occurred. My identity as biracial (Indian and White) also allowed me access to unique multicultural spaces in my research geography where racial diversity is encouraged. Finally, by personal identity as LGBTQ also made the ramifications of this study extraordinarily important. My history living in DC as an LGTBQ student inspired this study and motivated me to conduct my research with an attention to how my personal experiences mapped onto DC’s landscape. In short, this project was fueled and inspired by emergent ideas in urban and sexuality studies as well as my personal identity.

A few elements of my positionality provided challenges as I conducted my research. My student affiliation to an urban Ivy League school with a history of gentrification made it hard to earn trust among these communities that experiences this phenomenon today. It was hard to orient my research towards these topics without feeling hypocritical in my choice to document these spaces without acknowledging the history of the institution that I attend. Further, my male identity also makes it hard to fully encapsulate the experiences of LGBTQ women and gender non-conforming folks in my research. I did my best to research literature and document inclusive LGBTQ spaces in my research, but my positionality outside non-male LGBTQ experiences is important to acknowledge. Taking these successes and challenges in stride, however, the scope of this research does its best to be as inclusive and holistic as possible. It is grounded in my tangible experiences as an LGBTQ person of color while striving to inclusively enfold other experiences, either through diverse forms of public art (i.e. graffiti, photography, etc.) or spaces in DC. The next section addresses more of the concrete study methodologies that are informed by my ethnographic positionality to the subject of this research.

Study Methodology

The research methodology for this study is relatively straightforward. First, based on the author’s knowledge of DC’s LGBTQ neighborhoods, critical areas of research were initially identified. A rough list of neighborhoods, including Adams Morgan, U Street, Columbia Heights, Dupont Circle, and Mount Pleasant was compiled. Since the geographic area of these neighborhoods is quite expansive, a schedule was devised to systematically document the presence of public and mural arts in these areas. Based on the time required for documentation and analysis, one month was allocated for fieldwork. Between May and June 2024, fieldwork was conducted in each of the identified neighborhoods. On a given day, I walked long circuitous routes in these neighborhoods, taking photos of public and mural arts along the way. I did my best to walk along major streets and back alleyways to explore the multitude of different public forms of art that exist within these neighborhoods. The goal was not to document an exhaustive record of public art in these neighborhoods, but to capture important public art features that emerged during my walks through these neighborhoods. However, while my methodology was relatively rigorous at the start, I began to look at different forms and styles of art over time.

In the past, other attempts to document public murals have been successful, although narrow. A local map of murals in DC called MuralsDC provides a decent overview of murals across the city (“Map of MuralsDC Locations – MuralsDC,” n.d.). While the site provides important information that is also included in my study, the visual data—photographs—generated in this exploration pays specific attention to DC’s gayborhoods. Further, it includes informal forms of public art that might not be classified as murals: Graffiti, tagging, and street art that might be ignored by MuralsDC have already found a place within this dataset. Over time, my fieldwork became attentive to this nuance in what defines urban murals and public art. In response, this study offers a more inclusive and concentrated dataset that explores the pluralism of public art within LGBTQ-centered spaces of Washington, DC.

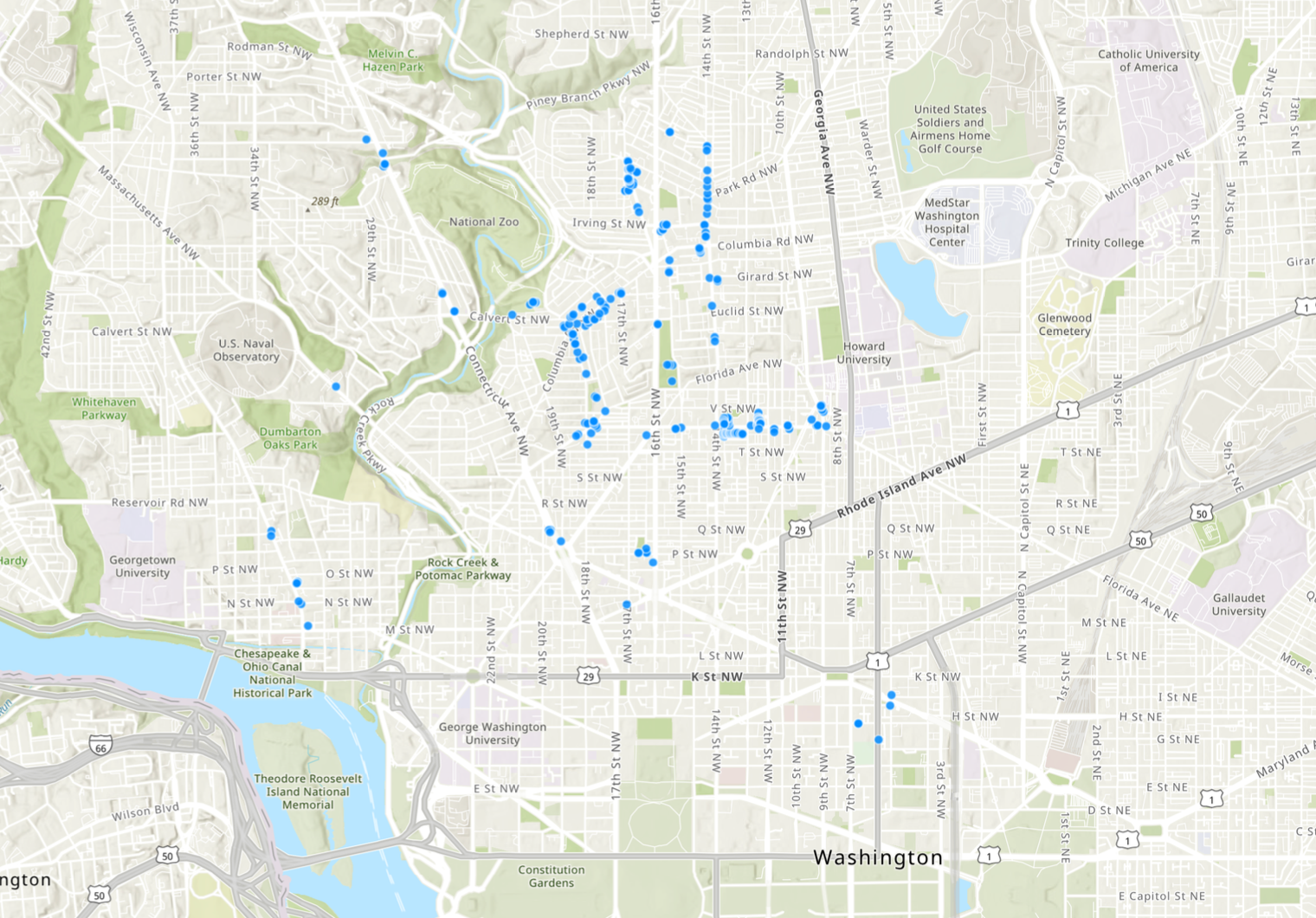

After a month of fieldwork and visual documentation, around 265 images were collected from around the study geography and were processed in two ways. The first used image metadata to map the location of these murals and public artworks. Photos were taken on a mobile phone (an iPhone 13 with a wide-angle lens that was useful for large murals or art projects) and therefore had latitude and longitude metadata that could be mapped on GIS. Images were compiled, cropped, and duplicates were removed; then, they were placed on a map of DC to pinpoint their exact locations the city. This produced a map of each fieldwork location in the city where public art and murals were observed (Figure 1). As of November 23, 2024, the dataset contains the same number of images from May and June 2024; as more murals crop up—and other forms of public art as well—this dataset may grow. For now, this manuscript works with the initial dataset collected from the summer but acknowledges that these initial findings may evolve over time.

Secondly, images were sorted based on the style and location of the art. This became an important means to separate forms of informal art—like graffiti—from commissioned murals and decorations on business storefronts. Nine Type Categories were used to classify images: (1) graffiti, (2) people, (3) sidewalk/street, (4) walls and buildings, (5) words, (6) parks, (7) sculpture and décor, (8) small motifs, and (9) photography. These Type Categories help distinguish the style and location of images within the dataset; it allows an appreciation of the liberal and inclusive nature of this study to include a plurality of public art forms.

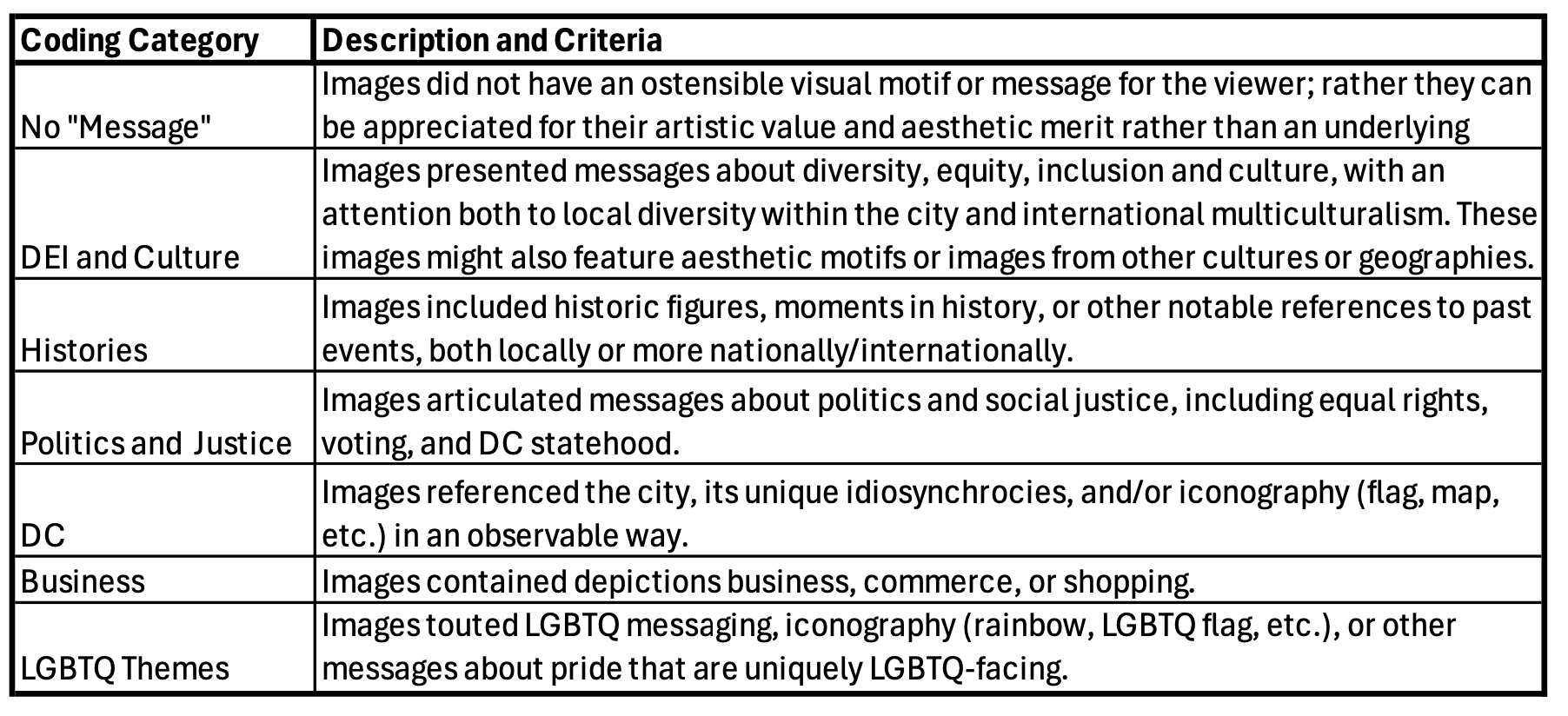

Next, open coding was used to associate images with certain motifs or visual messages that capture the discourse—or meaning—they provide for viewers. Using Robert Emerson, Rachel Fretz, and Linda Shaw’s methodologies for writing ethnographic fieldnotes, this open coding generated a set of interesting sorting categories (later called Coding Themes) for images with different visual messages. Then, this analysis deployed focused coding, a technique that uses the established themes generated through open coding to categorize the rest of the images (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 2011). Over time, ten different Coding Themes (encompassing visual motifs and messages) generated from open coding were used in focused coding, each with different criteria used to sort images (Table 1).

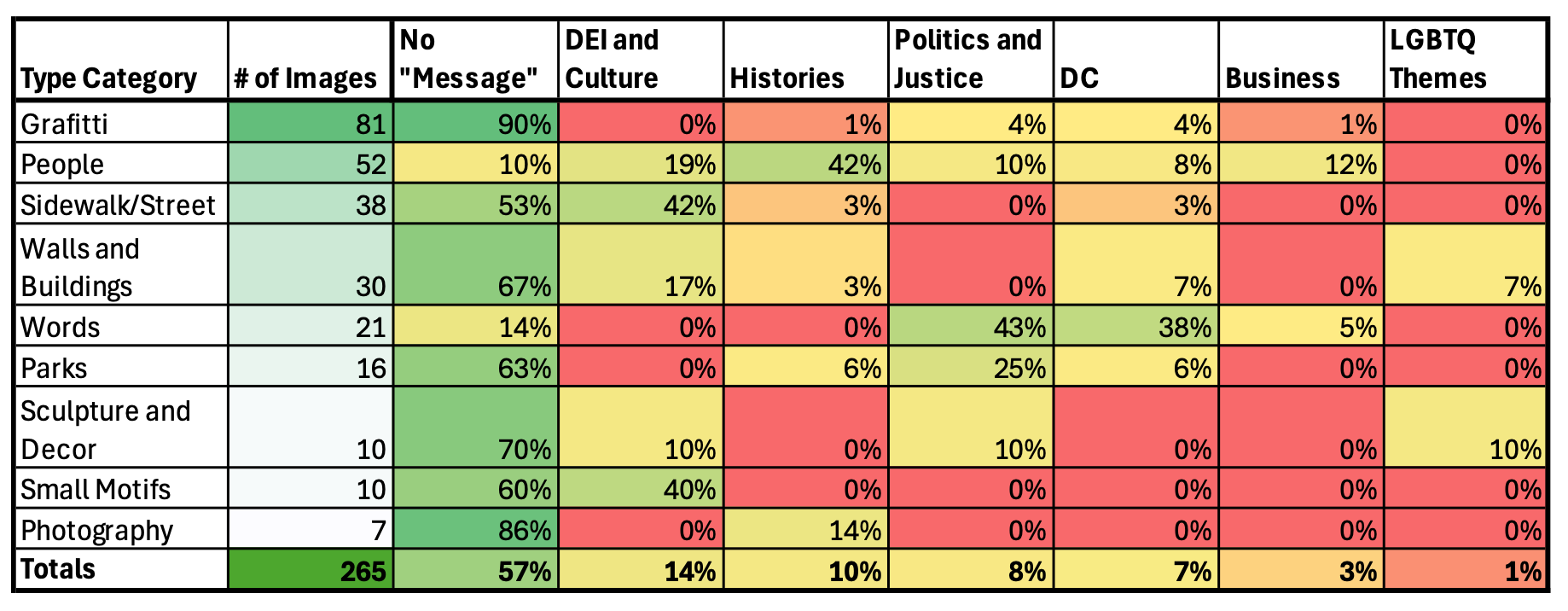

Using these Coding Themes and criteria, all images—across the nine Type Categories—were sorted to determine how many images in each Type Category were associated with each Coding Theme. Since the dataset often includes two images of the same public artwork (for especially large installments), the numerical quantity of images associated with each Coding Theme were then computed as a percentage (Table 2). This gave a breakdown of two things: (1) the percent of images in each Type Category associated with each Coding Theme and (2) the percent of images across all Type Categories fell within each Coding Theme. Using these two tables, important results are evident from this vast visual dataset.

Results

The results of this study point to a diminishing influence of LGBTQ themes in public art within Washington, DC’s gayborhoods. This underscores that LGBTQ placemaking through the arts has reduced as an essential practice in neighborhood development. However, large quantities of diversity, equity, inclusion, and history-focused public arts and murals were observed. This indicates the rising important of multicultural and inclusive discourse in Washington, DC within these gayborhoods in which minority communities reside. Furthermore, the largest quantity of public arts documented in the study were graffiti; out of 265 images, 81 documented graffiti (Table 2). The second most common was art showing people (N=52) and the third was art on sidewalks and streets (N=38). This indicates that more ephemeral, informal forms of art comprise the public displays within DC’s gayborhoods. Public artworks featuring people were the second common form of public art, showing a unique attention of these visuals to individual people important to these urban areas (Figure 2).

Sidewalks and streets were also common types of public artwork captured in this study. They show a unique attention to beautifying DC streetscapes and bringing public art “off the wall,” so to speak (Figure 3). Aside from these patterns in the Type Categories of urban public art, the different Coding Themes applied to these visuals is important to note.

The highest percentage (57%) of arts within the entire dataset were uncategorized or lacked an ostensible message; in other words, their purpose is purely aesthetic rather than oriented towards a specific message or goal for the viewer. The next two highest Coding Themes were DEI and Culture (14%, N=36) followed by Histories (10%, N=27). This suggests that there is a strong attention to diversity, equity, inclusion, and multiculturalism within DC’s gayborhoods. Similarly, public art commemorating moments or people in history are common, indicating widespread attention to the legacies that have influenced DC’s communities. Images demonstrating political or justice-related themes and those that had DC-specific themes appeared in about equal quantities; 8% of overall images (N=22) had political or justice themes compared to 7% (N=19) with DC themes. This displays how messages about broad political and topics in social justice appear almost just as frequently as DC-specific motifs. Within these groups, the question of DC statehood produces a unique overlap; DC-specific political messages enfold themes across these groups (Figure 4). In the data, images were separated by which Coding Theme was more evident, but this overlap is important to note.

LGBTQ-specific themes were the lowest, representing just about 1% of overall images (N=3). LGBTQ themes did comprise 7% of art on buildings and walls (N=2), and 10% of art themes (N=1) on sculptures and décor (Figure 5). But otherwise, these themes did not appear in other Type Categories. This result was particularly surprising because this research study took place during the lead-up to pride month; it is possible that the prominence of LGBTQ-themed public art might have increased across the month of June. This dataset, however, does not observe forms of public art that maintain a prominent connection to LGBTQ themes. LGBTQ placemaking efforts in the city does not appear to be a dominant effort within the landscape of public art and murals in the city. Based on the data of this study, placemaking efforts to establish diversity, equity, inclusion, multiculturalism, and recognize important histories is more frequent in contrast to LGBTQ-based efforts to map identity onto urban space through public art.

Moving more to the spatial organization of these murals, a large majority were documented on back alleyways of the city (this is computed by using the GIS repository of mural and public art images mapped directly onto the DC map which is available in the Data Availability Statement at the end of this manuscript). Graffiti was the main type of public art observed in these areas. Larger murals on buildings were observed along major streets within DC, though a few cropped up in the intersection between alleyways and streets with high traffic. These were mainly arts in the “Sidewalk/Street” and “Walls and Buildings” Type Categories. Otherwise, the GIS dataset of images mapped onto DC’s landscape offer a unique way to appreciate where and how public arts and murals are situated in the city. Many of the public art and murals that were documented in the study are quite spread out from one another. Some neighborhoods had a high concentration of public arts while other did not. This might be due to the challenging nature of documenting public art while walking on foot, but it may indicate how other neighborhoods like U-Street and Adams Morgan—which both have a high concentration of datapoints on the map—are more inclined to produce or invite public and mural artwork. Further investigation of public art in DC very well might add to the dataset and produce more insights about LGBTQ identities in the city. For now, the dataset presents future readers and scholars with an important, inclusive overview of public art within DC’s gayborhoods.

Discussion

Given the results of the study, graffiti artworks (N=81) are the most frequently observed. This might be explained because graffiti itself is a quick form of art that does not require the same municipal approvals as commissioned mural arts. Funding, zoning, and other policies weigh more heavily on the ability for commissioned mural arts to arise and endure within DC’s urban landscape. Murals about people is the second highest Type Category of photos (N=52). This might be supported by the fact that many prominent political and artistic figures found their footing in places around DC like U-Street. Prominent Black artists, musicians, and actors are commemorated because of their essential connection to DC’s Black history. Other people depicted in these people-focused public artworks are centered because of their notoriety and widespread admiration by people in the location of these murals.

The low quantity of LGBTQ-focused public arts and murals might be supported by previous literature about dissipating gayborhoods cited in the introduction of this study. Growing acceptance of LGBTQ identities might not necessitate placemaking as much for these communities. Furthermore, less cohesion and concentration of gay identities might explain why placemaking for LGBTQ identities is not observed within DC’s spatial geography. The dispersal of LGBTQ communities into multicultural areas might explain why themes of diversity and different cultures appeared most often among images with a clearly assigned Coding Theme. Consequently, as LGBTQ identities become more accepted, but racial and social stigmas about other identities persist, images associated with “DEI and Culture” would reasonably seek to combat this.

Otherwise, public art and murals an aesthetic purpose more than half of the time (57%), compared to other clear themes that show up about 43% of the time. The 14% difference between the amount of purely aesthetic and themed public arts indicates that perhaps, this difference is growing less significant. In other words, themed murals—talking about culture, history, and politics—might begin to catch up with the aesthetic, non-discursive murals documented in this study. This finding challenges some elements of the literature discussed in this manuscript. Literature supporting the dispersal of gayborhoods because of rising acceptance might explain some of these findings. With a rising tide of tolerance, placemaking practices might have become nonessential over time (Ghaziani 2014; Doan 2015; Collins 2004). However, a heavily political city, where polarization and division certainly exists, the need to establish messages about diversity, inclusion, and multiculturalism might explain these findings. The “DEI and Culture” Coding Theme is the second highest and far outpaces LGBTQ-specific public artworks. Consequently, the need to establish inclusive discourses through public art supports the rationale of this finding.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that LGBTQ placemaking through the public and mural arts is not common within Washington, DC’s urban fabric. In fact, most public and mural arts are designed to beautify neighborhoods. But a burgeoning number of public arts maintain messages about multiculturalism, diversity, and history. The main limitations of this study pertain to the dataset of images. Because public arts appear and dissolve rapidly, the dataset of this study is naturally growing and shrinking. Furthermore, this ephemerality means that this dataset is necessarily dynamic and might change over time, producing different results. For instance, the need for placemaking during a new federal administration tarnished by bigotry might arise with time. Establishing narratives to enshrine LGBTQ identities, feminism, and multiculturalism might be necessary as these identities come under threat. This body of research as a few important implications. Firstly, it produces a living repository of public and mural arts in Washington, DC’s gayborhood. It indexes multiculturalism and efforts of placemaking through the arts to show how social issues and interests are mapped onto public space. Secondly, it explores the changing queer geographies of Washington, DC and how public art and murals reflect changing paradigms about these gayborhoods. Finally, it offers a solid preliminary start for a much longer endeavor to investigate the changing social environment of Washington, DC as federal and city-wide politics change around the nation. As such, proposed areas of future research might explore multiculturalism and messaging in DC’s public art landscape over longer periods of time, especially following the 2024 Presidential Election. Public arts reflecting identity-placemaking practices might change with a new administration, different federal policies, and changing socio-political attitudes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to reserve this section for a few important acknowledgments for which this manuscript would not be possible. All my thanks to Professor Claire Panetta, who helped inspire and guide this project in its entirety. Special thanks to Dr. Justine Ellis from the Institute for Religion, Culture, and Public Life for advising my much larger ethnographic project from which this research inquiry is derived. Finally, all my thanks to my family who helped support this research in its entirety, from data collection to writing. Without their help, this would not be possible.

Disclosures

This research project is part of a much larger endeavor which was generously funded by the Institute for Religion, Culture, and Public Life at Columbia University through a summer research fellowship from June to August 2024. The author declares no conflict of interest in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data and analyses used in this study can be accessed at the request of the author. For those wishing to explore the GIS repository of images from this study, the link to map is here: https://columbia.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/basic/index.html?appid=5e834b5f6fbf43b0b8af1c639f2cbf6b. The data, tables, and spreadsheets used in this study can be accessed here through the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FMWZH8. Other information, including files from the full image dataset can be accessed by requesting of the author.

References

Ali, Erkan. 2018. “Introduction: Windows and Mirrors.” In Interpreting Visual Ethnography. Routledge.

Ball, Mike, and Greg Smith. n.d. “Technologies of Realism? Ethnographic Uses of Photography and Film.” In Handbook of Ethnography, 302–19. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608337.

Becker, Howard S. 1974. “Photography and Sociology.” Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communication 1 (Fall): 3–26. https://repository.upenn.edu/entities/publication/6f903707-c0dd-4be4-b1fc-79a79f531201.

Beemyn, Genny. 2014. A Queer Capital: A History of Gay Life in Washington D.C. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315819273.

Collins, Alan. 2004. “Sexual Dissidence, Enterprise and Assimilation: Bedfellows in Urban Regeneration.” Urban Studies 41 (9): 1789–1806. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000243156.

Doan, Petra L., ed. 2015. Planning and LGBTQ Communities: The Need for Inclusive Queer Spaces. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315756721.

Doan, Petra L., and Harrison Higgins. 2011. “The Demise of Queer Space? Resurgent Gentrification and the Assimilation of LGBT Neighborhoods.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 31 (1): 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X10391266.

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, Second Edition. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo12182616.html.

Ghaziani, Amin. 2014. “Conclusions.” In There Goes the Gayborhood?, edited by Amin Ghaziani, 0. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691158792.003.0008.

Greene, Theodore. 2015. “Gay Neighborhoods and the Self-Enfranchisement of the Vicarious Citizen.” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Ph.D., United States -- Illinois: Northwestern University. 1721391930. ProQuest Central; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Sociological Abstracts. http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/gay-neighborhoods-self-enfranchisement-vicarious/docview/1721391930/se-2?accountid=10226.

———. 2022. “‘You’re Dancing on My Seat!’: Queer Subcultures and the Production of Places in Contemporary Gay Bars.” In Studies in Symbolic Interaction, edited by Christopher T. Conner, 137–65. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0163-239620220000054008.

———. 2024a. “Introduction: Making Dupont Gay Again.” In Not in My Gayborhood: Gay Neighborhoods and the Rise of the Vicarious Citizen, 1–32. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/gree18988-002.

———. 2024b. “Still ‘A Very Gay City’: A Historical Impression of Washington’s LGBTQ Communities.” In Not in My Gayborhood: Gay Neighborhoods and the Rise of the Vicarious Citizen, 33–70. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/gree18988-003.

Harper, Douglas. 2002. “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586022 0137345.

Lewis, Nathaniel M. 2015a. “Fractures and Fissures in ‘Post-Mo’ Washington, D.C.: The Limits of Gayborhood Transition and Diffusion.” In Planning and LGBTQ Communities. Routledge.

———. 2015b. “Fractures and Fissures in ‘Post-Mo’ Washington, D.C.: The Limits of Gayborhood Transition and Diffusion.” In Planning and LGBTQ Communities. Routledge.

Lewis, Nathaniel M. 2017. “Canaries in the Mine? Gay Community, Consumption and Aspiration in Neoliberal Washington, DC.” Urban Studies 54 (3): 695–712. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26151371.

Lin, Wen. 2023. “Positivism, Power, and Critical GIS.” In The Routledge Handbook of Geospatial Technologies and Society. Routledge.

“Map of MuralsDC Locations – MuralsDC.” n.d. Accessed November 4, 2024. https://muralsdcproject.com/murals/map-of-muralsdc-locations/.

Mattson, Greggor. 2023. “A Post-Gay, Not-Gay, Very Gay, Un-Bar.” In Who Needs Gay Bars?: Bar-Hopping through America’s Endangered LGBTQ+ Places, 327–36. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503635876-038.

Modan, Gabriella Gahlia. 2007. Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place. New Directions in Ethnography Ser. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Muzzy, Frank. 2005. Gay and Lesbian Washington D.C. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub.

Pillai, Rupa. 2020. “Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Mapping Jhandis in Little Guyana.” In The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Cities. Routledge.

Pink, Sarah. 2024a. “Photography in Ethnographic Research.” In Doing Visual Ethnography, by pages 65-95, Second Edition. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857025029.

———. 2024b. “The Visual in Ethnography: Photography, Video, Cultures and Individuals.” In Doing Visual Ethnography, by pages 21-39, Second Edition. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857025029.

Roberts, Les. 2023. “Spatial Anthropology: Understanding Deep Mapping as a Form of Visual Ethnography.” In The Routledge Handbook of Geospatial Technologies and Society. Routledge.