Note — Religion, Public Art, and Placemaking in Washington, DC

This piece builds on earlier studies investigating public art in Washington, DC with a focus on LGBTQ placemaking. Now returning to the original religious lens, this note examines the geographies of worship and placemaking in the DC's evolving cultural history.

This article responds/adds to the report below, published using the following research and geographic exploration as a foundation

Preface

My earlier research on murals, public art, and politics in Washington, DC’s gayborhoods was initially part of a much larger project studying the religion-ization of public space in the nation’s capital. The funding that I received responded to a proposal I authored that related my experiences growing up in the city to the new ways I saw public spaces transformed into sites of spirituality and religious significance. But as I worked through my project, LGBTQ placemaking and politics became a central valence in my research. It therefore became central to shift the initial focus of the archive I was building to address this thematic frontier.

I do, however, want to return to the initial focus of the research—now that my LGBTQ placemaking findings are published—to share some insights that will guide the continuation of the project. Doing so also requires a bit of background to explain the analytical starting point for the project. This background begins with a general overview of the significance of religion in cities and moves to specific examples that illustrate this significance. Following these examples, the background will shift into discussing the power of art—public installations, murals, etc.—within this religion-city relationship.

Background

“Place matters,” writes Richard Flory, Executive Director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Life, “our perspectives on the world are shaped by many different social and psychological influences, but the specific ‘place’ that provides the context through which we interact with the larger world is of key importance in developing our ongoing understanding of that world. Religion is no different in this regard.” In the forward of the Routledge Handbook of Religion and Cities, Flory explores the longstanding connection between urban “places” and religion over the course of human history. For him, the very nature of religion “has not been able to ignore its urban space;” cities are “the literal context in which faith communities have flourished” (Flory 2020). The earliest cities in Mesopotamia have followed in these words, often situating urban centers and community life around prominent religious centers of worship (Day and Edwards 2020). Even the very idea of cities themselves have been central throughout religious discourse for millennia. St. Augustine’s text City of God imagines the role of cities both as a place of paradise and eternal damnation; the cities of Mecca and Jerusalem have remained central to the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faiths; and the city of Varanasi remains sacred for Buddhists and Hindus (Day and Edwards 2020).

New ways of conceptualizing spirituality and religiosity within urban spaces have revealed themselves in unexpected ways. Some examples include the substantial placemaking for the Sri Siva-Vishnu temple in suburban Washington, DC. It provides a new way for diasporic Hindu communities to create a physicalized connection to their cultural origins and religious communities across the globe (Waghorne 1999). Away from the suburbs, cities like New Orleans have become the backdrop for religious placemaking in the wake of sweeping redevelopments after Hurricane Katrina. In December 2008, residents performed a vigil at a statue of Martin Luther King Jr. to honor victims of violent crime in their neighborhood and to call for peace among residents (Carter 2014). For New Orleans and suburban DC, this practice of urban religious expression is central in building a more grounded and connected social fabric. Based on these two examples alone, it is easy to observe that urban areas have become necessary sites for religious expression and the spatialization of community memory. Art, however, has become a critical tool for urban dwellers to preserve and amplify their community connections.

Michael McLaughlin documents how mural arts in Harlem during the New Deal engaged “racial aesthetics” to bring a religious significance to their surroundings (McLaughlin 2020). Amanda Furiasse explores how the dance troupe Ektesa utilized a hybridized Ethiopian-Jewish artistic style to perform ritualistic choreography and foster a sense of belonging for immigrant communities in Israel (Furiasse 2020). In 2022, the Adams Morgan neighborhood used mural arts to protest the seizure of Adams Morgan Plaza, which led to the death of Miguel Gonzales, a well-loved unhoused resident of the plaza (Moyer 2022). Today, Washington, DC boasts other gathering spaces and heritage sites to mourn, celebrate, remember, and grieve together. It also boasts a rich history of cultural, religious, and ethnic plurality that responds to and is informed by political change. The social conversation between places of worship and public art show how religiously motivated buildings and mural arts play a role in the cultural politics and placemaking practices of cities like DC. But art specifically can help us understand how DC residents utilize a new form of religious practice that situates itself beyond the places of worship that populate the city.

Initial Findings: Neighborhoods and Places of Worship

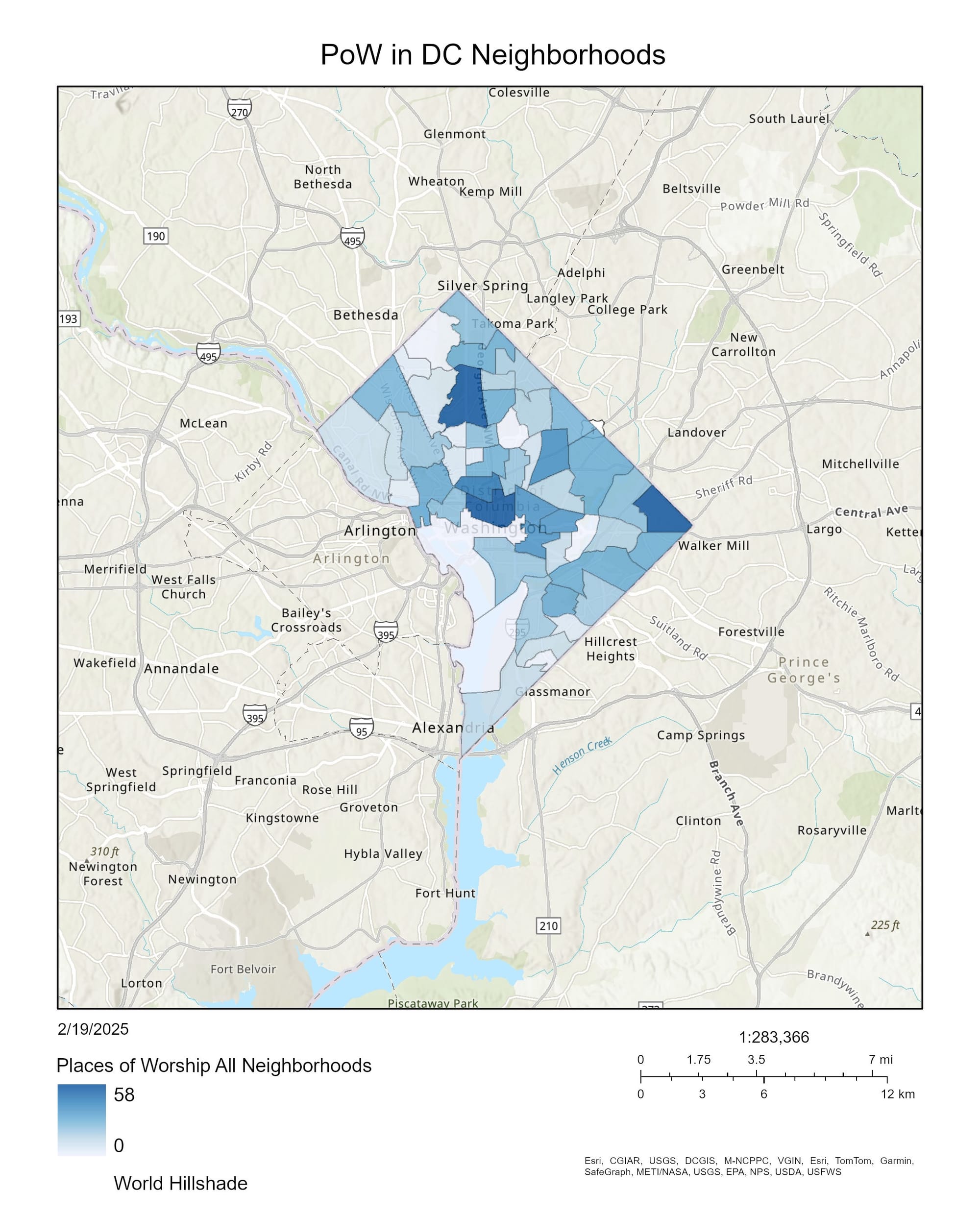

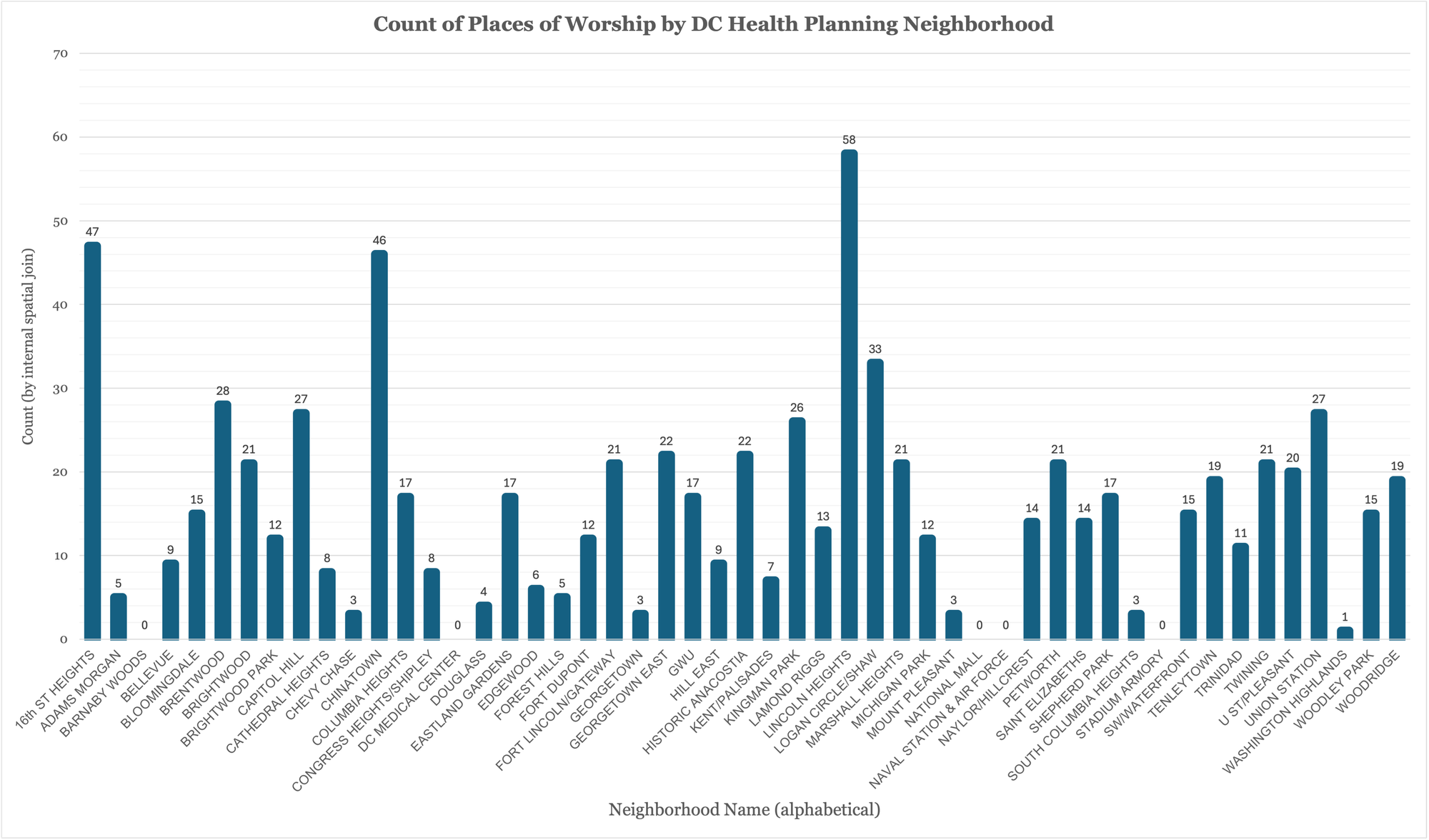

While engaging the existing spatial archive of public art sites in DC will require more work, my initial spatial analysis of the city, its neighborhoods, and sites of worship shows a promising jumping-off point for my future explorations. In other words, understanding the existing landscape of religion, culture, and public life in DC is necessary before working with the spatial archive of public art I developed. The spatial analysis of places of worship in each DC neighborhood (Figure 1) yields results that advance this understanding quite significantly.

The three neighborhoods that contain within them the most places of worship are Lincoln Heights (58), 16th Street Heights (47), and Gallery Place/Chinatown (46). The neighborhood that contains the fourth largest quantity of places of worship is Logan Circle (33) which trails Gallery Place/Chinatown by double-digits. But the reason why these neighborhoods contain so many places of worship is fascinating; to a degree, it stands to reason that these neighborhoods have specific qualities and histories that explain the numbers observed in this chart (Figure 2). Initial research into these neighborhoods agrees with that hypothesis.

The history of Lincoln Heights is rooted within African American unity and Christian practices. As the neighborhood grew over time, “Christian rituals and church traditions evolved” and sacred gatherings began to connect the community in widespread ways (The Deanwood Historical Committee 2008, 63). The early places of worship established during the early years of the neighborhood’s founding created an early tradition of religious leadership that continued for many years following. These sites left a legacy of religious dedication and expanded to include “educational guidance and financial wisdom” (The Deanwood Historical Committee 2008, 63). People within the community also shared common Christian values and “the desire for suitable accommodations for religious worship” (The Deanwood Historical Committee 2008, 63). And despite these commonalities, Lincoln Heights and Deanwood—the sub-neighborhood contained within—honored the diversity of religious beliefs and denominations celebrated by its people. Some of the earliest churches in the neighborhood were the Contee African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church built in 1885, and the First Baptist Church of Deanwood completed in 1901. These churches from the early history of the neighborhood fed into a much longer tradition of building places of worship in Lincoln Heights and Deanwood. In that respect, the church presence in the neighborhood has continued to grow (The Deanwood Historical Committee 2008, 63). The early history of African American unity, Christian practices, religious diversity, and expanding church presence in Lincoln Heights helps explain why it has the most places of worship than any other neighborhood in Washington, DC.

16th Street Heights, however, has a slightly different explanation. The neighborhood of 16th Street Heights also maintains an endemic sense of diversity. According to an article from the Washington Post, the neighborhood is frequently listed as one of the most diverse in the city (Seck 2022). In that sense, it shares an innate sense of pluralism with Lincoln Heights. But the reason why so many places of worship line the neighborhood’s central 16th street throughfare is slightly different. Firstly, the neighborhood is built around a roadway that connects it directly with the downtown area. 16th street cuts through the DC diamond, splitting it into roughly equal halves, tracing a route from the top of the city through Lafayette Square and towards the White House (Wei 2017). The street’s ability to remain a “prominent boulevard” connecting the downtown and uptown areas of the city made it prestigious, thus making it an appealing location for many houses of worship. St. John’s Episcopal Church, built in 1816 (in close proximity to the White House), has been attended by every US president since James Madison (Wei 2017). All Souls Unitarian Church, founded just five years after St. John’s, moved from its 14th and L street location to 16th Street Heights; President William Howard Taft laid its new cornerstone along 16th Street in 1913 (Wei 2017). The neighborhood’s connection to the White House and embrace of social justice and diversity explains why the area is so heavily populated with religious sites. Moreover, the geographic positioning of the neighborhood and 16th Street’s longstanding connection to White House residents reveals how the area itself coheres both religious and political histories.

Gallery Place/Chinatown exemplifies this even further. The Gallery Place/Chinatown area of D.C. has a more complicated history of religious plurality than its counterparts. Early religious traditions in Lincoln Heights and the prestige of 16th Street catalyzed by its advantageous location help explain why these neighborhoods contain the largest quantities of places of worship. Gallery Place/Chinatown, on the other hand, is all but a mystery. Current literature lacks specific answers as to why the neighborhood itself contains so many sites of religious significance and worship. But one possible hypothesis combines an attention to Gallery Place/Chinatown’s history of immigrant entrepreneurship that grew local economic capital. This growth perhaps empowered neighborhood residents with the means to transform urban space into places of worship where their religious pluralism could be enshrined. Ching Lin Pang and Jan Rath introduce the idea of immigrant entrepreneurship and its potential to transform neighborhoods like Gallery Place/Chinatown into tourist sites:

“Immigrants are, sure enough, involved in this economy as wage laborers or as entrepreneurs. In their capacity of entrepreneurs, immigrants are active as producers of a range of tourist services and attractions, varying from restaurants, travel agents and gift shops to festivals and street parades. There can be no mistake that these entrepreneurs are central to the transformation of shopping strips or shopping malls into ‘exotic’ ethnic precincts” (Pang and Rath 2007, 3).

The proliferation of Chinatown as a tourist attraction fueled by immigrant entrepreneurs allowed the neighborhood to achieve widespread access to vital economic resources and vibrant ethno-social networks that strengthened this growth (Pang and Rath 2007, 6). This increasing economic capital, now available to locals, may have expanded their ability to discretionarily designate and transform urban space. Bringing religion into this discussion, the way immigrants often infuse religiosity into their appropriations of public space would explain the growth—and widespread presence—of religious sites in Gallery Place/Chinatown (Irazabal Zurita and Dyrness 2010, 361).

Closing

The findings examined above offer promising explanations beneath the spatial analysis of this project. Lincoln Heights and 16th Street Heights both contain complex histories that help explain the large number of places of worship within them. On the other hand, Gallery Place/Chinatown remains quite nebulous. I offer that rising immigrant entrepreneurship allowed locals to build more places of worship in the neighborhood through increased economic capital and the desire to infuse urban placemaking with social-religious priorities. Further research may offer a more substantial or even different hypothesis. For now, the early findings of this project offer promising areas for future investigation that may answer significant questions, including: “how does public art index the relationship between religion and federal/state politics in the nation’s capital?” and “based on Gallery Place/Chinatown’s proximity to the political center of Washington, DC, how might we explain the proliferation of religious sites in the neighborhood?”

Future findings may give an answer to these questions, but for now, they will guide the unfolding scope of this project and its trajectory within an urban landscape marked increasingly by tenuous politics and changing religious geographies of heritage, expression, and culture.

Bibliography

Carter, Rebecca Louise. 2014. “Valued Lives in Violent Places: Black Urban Placemaking at a Civil Rights Memorial in New Orleans.” City & Society 26 (2): 239–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ciso.12042.

Day, Katie, and Elise Edwards. 2020. “Introduction.” 2020. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429351181-1/introduction-katie-day-elise-edwards?context=ubx&refId=80560e59-b1c7-4aac-a906-0d1cfcb25e5c.

Flory, Richard. 2020. “Foreward.” In The Routlegde Handbook of Religion and Cities, xvii–xx. London: Routledge.

Furiasse, Amanda. 2020. “The Intersection of Immigration, Social Conflict, and Art: Dance and Identity in ‘East’ Haifa.” In The Routlegde Handbook of Religion and Cities, 221–34. London: Routledge.

Irazabal Zurita, Clara E., and Grace R. Dyrness. 2010. “Promised Land? Immigration, Religiosity, and Space in Southern California” 13 (4): 356–75. https://doi.org/10.7916/D80C4TJF.

McLaughlin, Michael. 2020. “Religious Space in Public Art: The New Negro and New Deal in Harlem.” In The Routlegde Handbook of Religion and Cities, 209–20. London: Routledge.

Moyer, Justin Wm. 2022. “Adams Morgan Mourns a Man Who Died Homeless, Steps from His Childhood Home.” Washington Post, May 10, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/05/07/dc-homeless-death-miguel-gonzales/.

Pang, Ching Lin, and Jan Rath. 2007. “The Force of Regulation in the Land of the Free: The Persistence of Chinatown, Washington DC as a Symbolic Ethnic Enclave.” In The Sociology of Entrepreneurship, 25:191–216. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-558X(06)25006-7.

Seck, Hope Hodge. 2022. “Changes Are Coming to 16th Street Heights.” Washington Post, May 25, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/05/25/where-we-live-16th-street-heights/.

The Deanwood Historical Committee. 2008. Washington, D.C.’s Deanwood. Arcadia Publishing.

Waghorne, Joanne Punzo. 1999. “The Sri Siva-Vishnu Temple in Suburban.” Gods of the CIty: Religion and the American Urban Landscape, 103–31.

Wei, Deborah. 2017. “Dozens Of Houses Of Worship Line 16th Street NW. Here’s Why.” DCist (blog). August 16, 2017. https://dcist.com/story/17/08/16/houses-of-worship-16th-st/.