Working Paper — Histories of Privatization: Examining Culture, Legal Conflict, and Economic Transformation at Adams Morgan Plaza in Washington, DC

This study uses census data and primary source documents to understand why Adams Morgan Plaza was privatized and how these changes are challenged. The results shed new light on how legal battles and economic pressures shaped the development of a central neighborhood landmark.

This is a working paper and serves as a document/research report on an urgent issue presented to the public before publication in a research journal (either at SCOPE or another journal outside of UEI).

Abstract

Public spaces are disappearing at alarming rates as cities face mounting housing, economic, and social issues. Adams Morgan Plaza in Washington, DC is no different. Over the past several years, the Plaza has experienced numerous changes that have radically altered the neighborhood. It sparked community outrage and an ensuing lawsuit that wound way, slowly, through the DC courts. This study uses census data and primary source documents to understand why Adams Morgan Plaza was privatized and how these changes are challenged. The results shed new light on how legal battles and economic pressures shaped the development of a central neighborhood landmark. Its history as a theatre and communal epicenter is obscured by its liminality. The Plaza today contradicts Adams Morgan’s legacy of diversity and artistic culture, but also finds itself on a new path: to create affordable housing. These findings provide insights into an ongoing history of change, cultural expression, and community within a vibrant neighborhood of the nation’s capital.

Keywords

Washington, DC; housing; historic preservation.

Introduction

Adams Morgan Plaza emerged from the liminal background of my running route one rainy Thursday afternoon when I almost crashed into a police officer standing near the bus stop. Before I had a chance to really process my close encounter, the crosswalk light had already switched back to red and I was trapped on my side of the street, only one and half miles away from the end of my route. Instead of browsing through my podcast library or even checking my mile splits, I glanced back at the plaza, behind the mysterious chain-link barriers, and really took it in for the first time. I saw the way the entire plaza had created an atmosphere, an environment that not only intrigued me but invited me to stay. That would be the case if it wasn’t for the fences. In front of one of these tall chain-link barriers on the perimeter of the plaza, the police officer I almost hit was standing, watching a man on a ladder power wash a mural from the plaza’s upper wall (Figure 1). Only one day earlier, it read “FREE OUR PLAZA PARA MIGUEL.” That was over two years ago.

On that rainy day in 2022, the private development firm Hoffman & Associates closed Adams Morgan Plaza to the public. Its re-acquisition sparked controversy in the community and an ensuing, lengthy legal battle in the DC courts. Neighborhood residents, local DC residents, and other interested parties became increasingly invested in the future of the Plaza because of its history. Adams Morgan Plaza was an important theatre and cultural center of the Adams Morgan Neighborhood before becoming an open-access public square. Its new embroilment against the backdrop of DC’s housing landscape was unprecedented and sparked two important questions. What is the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition? What factors determined its future? This paper attempts to answer both these questions with two combined methodologies. The first methodology relies on primary and secondary sources—including scholarly articles—to detail the history of Adams Morgan, its surrounding neighborhoods, and Adams Morgan Plaza itself. The second mobilizes census data to understand why the Plaza became involved in DC’s housing economy. In this manner, this paper finds that the Adams Morgan Plaza’s transformation into an affordable housing center differs profoundly from its history. The paper points to a possible economic impetus for this historic moment in the Plaza’s history observed through worsening poverty rates between 2021 and 2022.

I begin this paper with an overview of the methods used in this study, including a personal positionality of the subject matter. Following, I present my results in three predominant historical categories: (1) a pre-plaza history, (2) a legal history, and (3) a contemporary economic history. Finally, I conclude with a summary of my findings and a consideration of future scholarship.

Research Scope and Methodology

This research scope and methodology section is organized into three main sections. The first explains the research methods used to investigate the early history of the Adams Morgan Neighborhood up until the Plaza became a feature of the neighborhood after 1976. The second expands on the legal research methodology used in this study to elucidate the legal history of the Plaza during and after 2017. These sections attempt to answer the first critical research question in this study: what is the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition? The final section outlines the economic methodologies used to provide a possible answer to the final research question in this study: what factors determined the future of Adams Morgan Plaza? I conclude this scope and methods portion of the paper with a consideration of this study’s potential limitations.

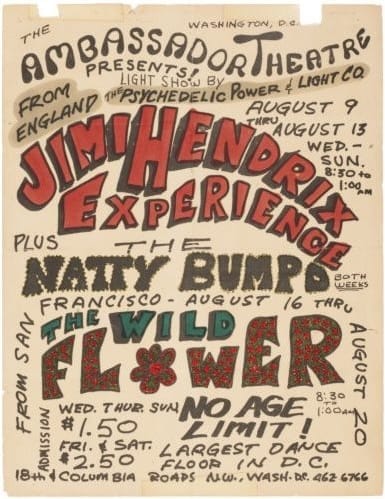

To understand the early history of Adams Morgan, I began looking at historical records, photos, and books about the name and establishment of the neighborhood. I used news articles from the Washingtonian that detail the early history of Adams Morgan and the moment when the neighborhood was officially recognized through its name. Following, I heavily consulted the work of Celestino Zapata and Josh Gibson, who wrote a book documenting the evolution of the Adams Morgan neighborhood through photographs. I reference the scholarly work of Robert Manning, who writes about the early demographic history of DC as a formerly predominantly Black city during the 1970s. Doing so helps provide a cultural background of the Adams Morgan area for a potential readership unfamiliar with the neighborhood and its connection to DC’s broader urban history. I consult a few and news articles that discuss the early disasters that plagued the site of Adams Morgan Plaza, including the collapse of the Knickerbocker Theatre in 1922. Using these sources as a springboard, I follow the early history of the Plaza after 1922 and its rejuvenation into the Ambassador Theatre using a combination of online sources, podcasts, and primary sources, including original posters. My coverage of the Plaza’s pre-history is narrated through 1976 before it was officially acquired and turned into a public easement for the neighborhood. Then, my research resumed in 2017 when SunTrust acquired the area of the Plaza and transformed it into a community fixture. I draw on more contemporary and local news sources to uncover the 21st-centuryst history of the Plaza and its early legal history.

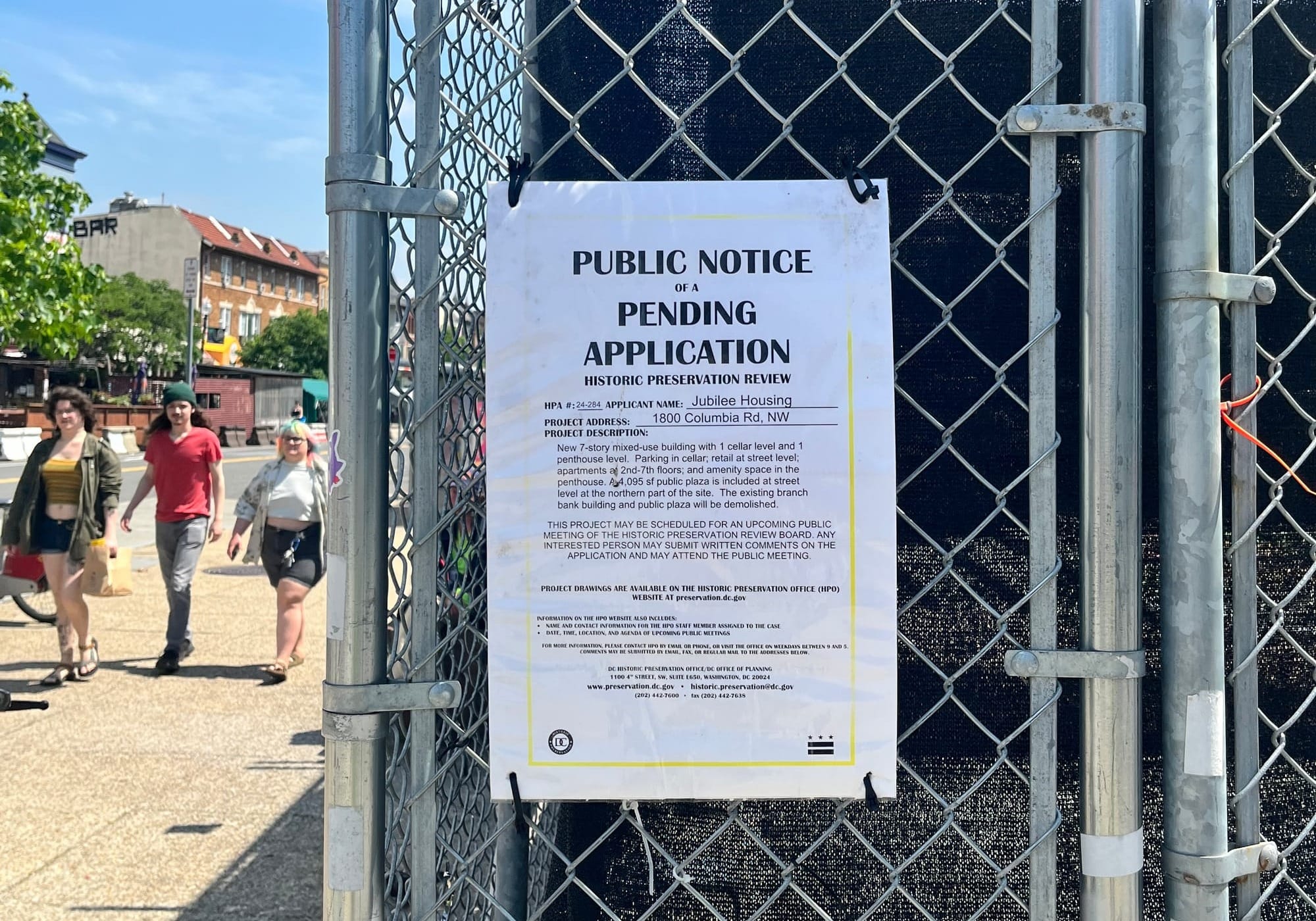

The legal history section of this study mostly draws from news sources, websites, and original legal documents from the case as it bounced between the DC Circuit and Superior Courts. I begin first by researching news articles and updates about the status of the Plaza since neighborhood residents filed suit against the private development firm Hoffman & Associates who purchased the site. I trace the chronology of the lawsuit over the following years and draw on news updates, a website run by Adams Morgan residents, and original legal documents to guide this step of my research. As the chronology approaches the present day, I turn to fieldwork to supplement the other sources used in this study. My background as a DC resident afforded me the ability to make regular visits to the Plaza to look at original construction orders and postings at the site. The closure of the Plaza and its chain link fences posed a challenge when accessing physical parts of the Plaza (Figure 2).

Consequently, potential avenues to conduct oral histories at the site of the Plaza were also limited. I pivot to using photographs of documents posted near and around the fences of the Plaza as well as public records to fill potential gaps caused by the physical restrictions in place. This becomes especially important as I document Jubilee Housing’s current construction plans for the Plaza that were publicized in April 2024. After this review of the current construction plans for the Plaza, I turn to the final research question posed in this study: what factors determined the future of Adams Morgan Plaza?

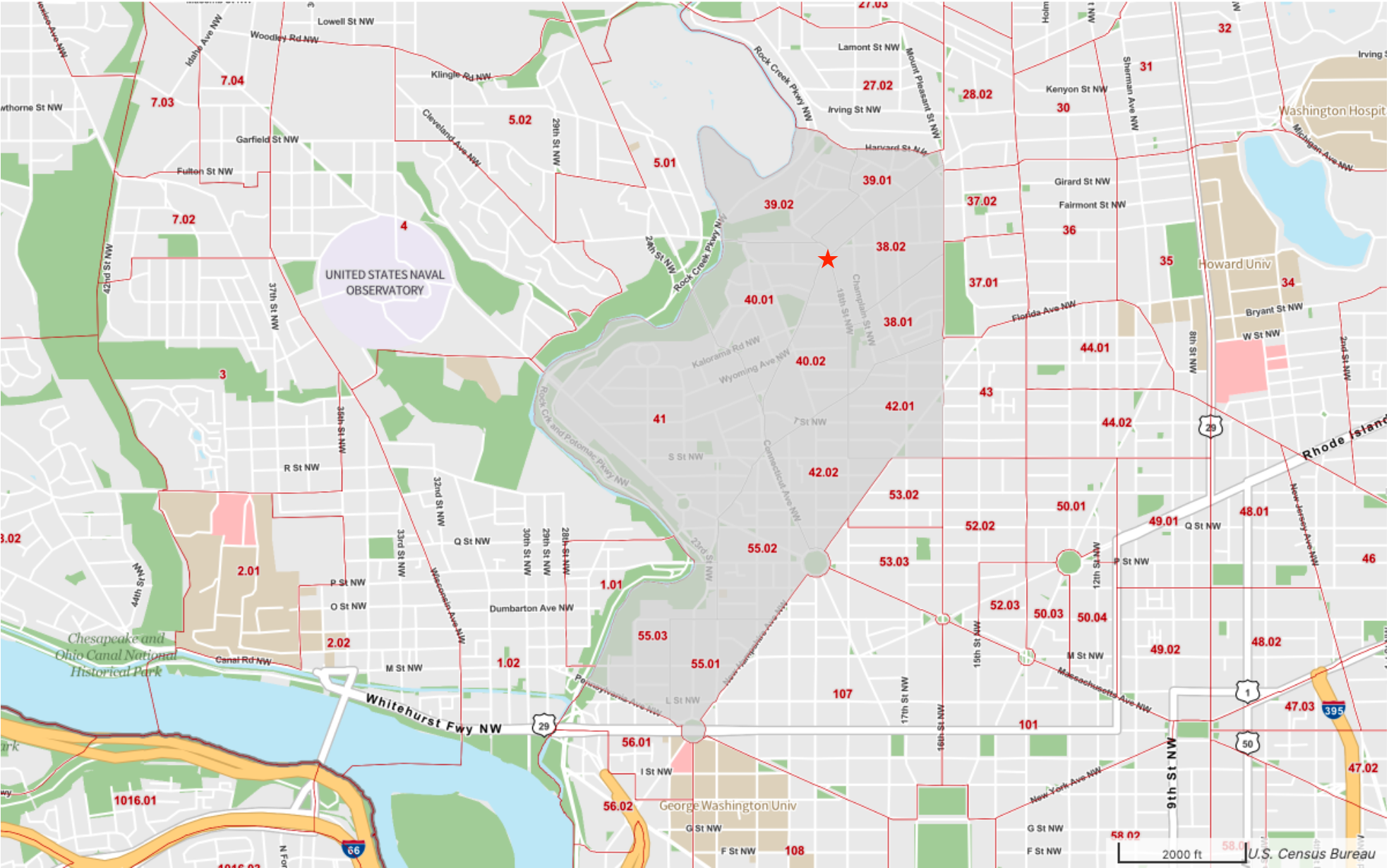

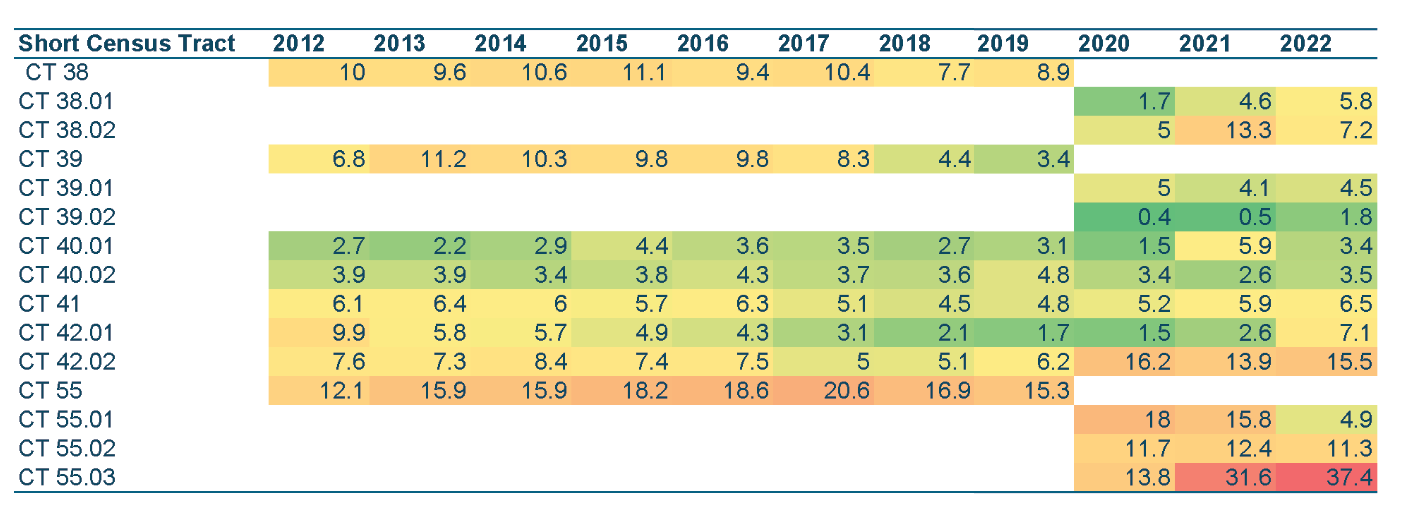

To propose a potential answer to this question, I draw on census data and theories of urban geography to understand the economic history of Adams Morgan and its Plaza. I began first by identifying the important geographic areas for my research and I do so by using Homer Hoyt’s Sector Model of urban geography. Adams Morgan’s proximity to the historic Kalorama Triangle neighborhood of DC made Hoyt’s Sector Model the most useful geographic framework because it accounts for directional biases in urban land use and value catalyzed by factors like historical zoning (Warf 2010). This allowed me to select geographies to use for my census analysis that aligned with traditional theories like the Concentric Zone Model while factoring in DC’s historic zoning practices. Following this geographic inquiry, I began by investigating data provided on the US Census Bureau website (US Census Bureau, n.d.-b). I identified the boundaries of my research area using my earlier geographic analysis and selected the census tracts that encapsulated the Plaza, the surrounding Adams Morgan neighborhood, and its border community (Figure 3).

Then, I sourced data from the American Community Survey’s (ACS) five-year estimates of the poverty rate within the selected census tracts. The five-year estimates provide important data over many years and utilize “estimates based on data collected during the 60 months of the five most recent calendar years”(US Census Bureau 2022). These estimates are drawn “from all statistical, legal, and administrative entities, including census tracts, block groups, and small incorporated places, such as cities and towns” (US Census Bureau 2022). This allowed a highly detailed investigation of economic trends throughout all the census tracts identified in this study. Furthermore, the ACS five-year data utilize a system of ratio estimation that applies two sets of weights: one to each sample person recorded, household person, and group quarters person, and one to each sample housing unit (US Census Bureau 2022). The ACS’s ratio estimation takes advantage of independent population estimates provided by the US Census Bureau to optimize precision and to correct “for under- or over-coverage by geography and demographic detail”(US Census Bureau 2022). Therefore, the ACS five-year estimates provide the most accurate information for small population areas like individual census tracts that are the subject of this study. While they are not always the most current because one-year estimates do not survey individual census tracts, they are an accurate data metric to assess in this study, where analyzing separate census tracts is critical (US Census Bureau, n.d.-d).

I sourced two types of data from the ACS five-year estimates from 2012 to 2022: the percent of the population for whom poverty status is determined (including those in housing units) and the total number of housing units. Using a percentage rather than a total population living in poverty was chosen to account for varying population sizes between census tracts. On the other hand, the total number of housing units per census tract was selected as a way of measuring the overall fluctuation in housing units within each census tract. Observing both poverty rates and total housing units between 2012 and 2022 is a hopeful way of seeing how the amount of housing changes alongside poverty rates within the geography of this study. Although both metrics are observed together, this study does not propose that poverty percentages and total housing units are correlated datasets. Rather, these metrics are overlayed to provide a multi-focal image of how economic factors determined the Plaza’s future, especially Jubilee Housing’s involvement and their proposals to build low-income housing on the Plaza itself. Both strains of data were compiled by year and analyzed using Microsoft Excel to produce simplified line graphs and data tables for this study.

A History Before the Plaza

This section investigates the early history of the Adams Morgan neighborhood to answer the first research question of this study: What is the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition? This section focuses specifically on the first part of this question: the history of Adams Morgan Plaza before its re-acquisition. The name “Adams Morgan” was originally tossed around during the 1950s and formed by conjoining the names of the all-white John Quincy Adams and now-defunct all-black Thomas P. Morgan Schools (Leaman 2008). While their partnership in the community was unofficial at first, their cooperation began in earnest after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of integration in 1954 (Leaman 2008). Together with local activists and residents, the schools created the first Adams-Morgan Better Neighborhood Conference to peacefully desegregate the two schools. The hyphenated name remained as a way of distinguishing the neighborhood from others nearby but eventually fell out of use. Josh Gibson, an expert and writer about the neighborhood argues that the use of the hyphen is designed to join two “easily identifiable” geographical areas into a single name. Since the two schools did not occupy purely distinct locations, the hyphen disappeared (Leaman 2008; Zapata and Gibson 2006).

Following the establishment of the neighborhood’s official title, the development of Adams Morgan began under the careful guidance and encouragement of Mary Foote Anderson. Anderson, the wife of a Missouri Senator was a “dedicated crusader of the early neighborhood,” and Sixteenth Street grew dramatically because of her efforts. Meridian Hill Park—also known as Malcolm X Park—now occupies the land where her home and castle once stood (Zapata and Gibson 2006). Over time, a variety of plans for an expanded White House and Lincoln Memorial were proposed in Adams Morgan, but few reached fruition; today, a host of embassies reside on the perimeter of the neighborhood along Sixteenth Street (Zapata and Gibson 2006). In the 1960s and 1970s, Adams Morgan became a site of much civil unrest like other parts of Washington, DC, and America as a whole. The arrival of the automobile allowed people to move freely in and out of the neighborhood; during this time, dramatic demographic change transformed the neighborhood and indeed, the city at large. The outflux of people from the neighborhood allowed Adams Morgan to become an increasingly affordable housing area for many, while progressive ideas about civil rights and Black Power found substantive footholds in the area (Zapata and Gibson 2006).

During this time, DC’s background as a majority-Black city helps to position Adams Morgan in the multicultural historical fabric of the city. In 1970, the city boasted an absolute Black majority of almost 70 percent (Manning 1998). The years prior also saw an increasing amount of Black urban residents moving into the city; in 1970, 27.2 percent of African Americans resided in the suburbs of DC while around 90 percent of white residents were living there by comparison (Manning 1998). This stark contrast in urban versus suburban racial composition is what motivated many to begin calling DC “Chocolate City,” an homage to its rich cultural history rooted in Black and African American culture. In the years following, widespread civil rights movements across DC brought increasingly higher amount of immigrant populations to the city (Manning 1998). This wave of immigration came on the heels of the 1960s DC riots that prompted large-scale flight of white families and landowners who began moving to the suburbs to avoid the violence (Manning 1998). As a result, businesses, homes, and other properties in DC’s urban core were vacated, allowing a surging immigrant population to begin establishing roots in the city (Manning 1998). The new demographic composition of the city was far more diverse as a result: by the 1990s, the city boasted a 72.6 percent minority population; however, there was a large amount of flux in between racial subgroups (Manning 1998). Added immigrant communities in the district began to chip away at the majority maintained by Black and African American residents. By 1990, Black and African American urban residents comprised only 65.1 percent of the population compared to their 71.1 percent majority in 1970 (Manning 1998). Overall, this growing economic diversity continued; it set the stage for the urban world in which Adams Morgan finds itself in contemporary DC.

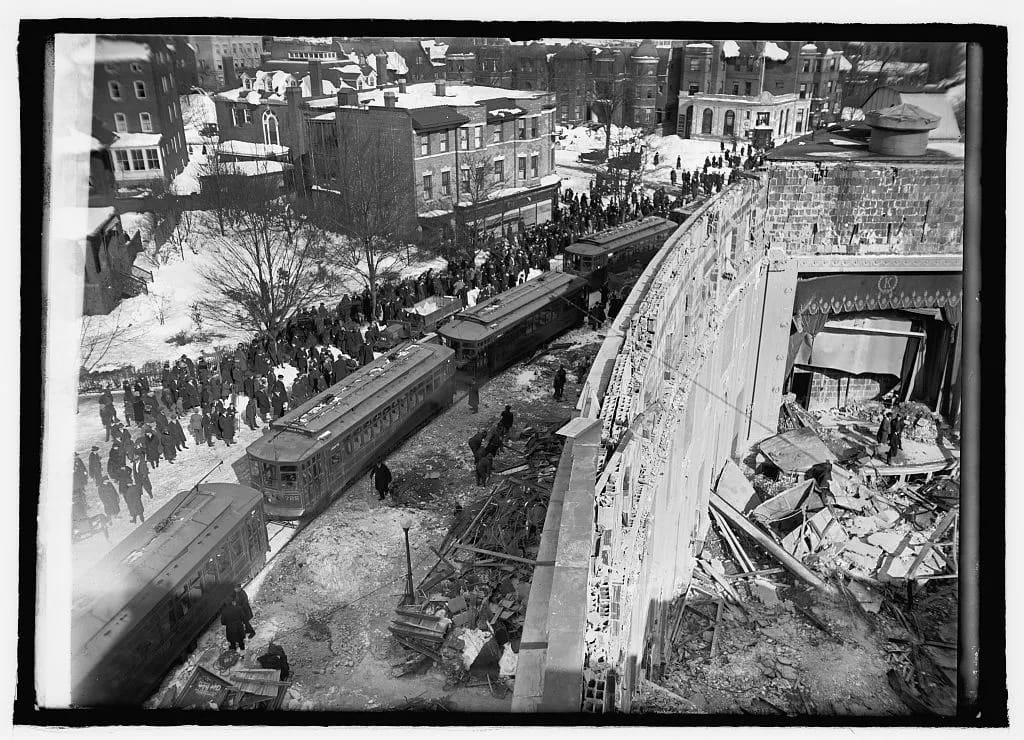

Adams Morgan Plaza used to reside on a plot of land that used to be the Knickerbocker Theatre. On January 28, 1922, the theatre collapsed after a bout of heavy snowfall, injuring a total of 133 people and killing 98 (Gormly 2022). After the collapse (Figure 4), the next three days included multiple rescue efforts and an investigation of the cause of the collapse that found faulty construction to blame (Felix, n.d.).

In the aftermath, a series of lawsuits and widespread public outcry led to the implementation of several important building codes for Washington, DC (Gormly 2022). Following the collapse of the Knickerbocker Theatre, Thomas Lamb was hired in 1923 to begin construction of the new Ambassador Theatre using the shell of the Knickerbocker as a foundation (Bryan 2012). Several years later, prominent rock performer Jimi Hendrix left tour with The Monkees and performed at the Ambassador for five days starting August 9, 1967 (Fraley 2022; Wolf Trap 2017). The Jimi Hendrix Experience was advertised throughout the neighborhood and drew numerous crowds to the Ambassador during those five days of summer where anyone—regardless of age—could experience Hendrix’s performance (Figure 5) (Namdi 2017; Krulik 2017).

The Ambassador eventually closed in January 1968 due to a shortage of funding and a series of unsuccessful musical attractions that failed to generate revenue for the establishment (Schweitzer 2017). The theatre was eventually demolished, and the site was set to change hands in 1976 when the vacant plot became the prospective site of a new establishment. During that year, the bank Perpetual Federal Savings and Lending wrote a letter to Adams Morgan Residents proposing to build a branch on the grounds of the former Ambassador Theatre. They also wrote in the letter that they would build a plaza for public use as part of an agreement to dismiss federal complaints against their racist lending practices (Austermuhle 2017; Maxit 2021). Eventually, the land was acquired by SunTrust Bank—now Truist—to build their branch, and the public easement purpose of the Plaza was brought about informally. While Perpetual wrote about its goal to establish a Plaza in Adams Morgan for communal use in their letter, SunTrust articulated no such claims. Nonetheless, before the Plaza’s re-acquisition by development firm Hoffman & Associates in 2017, the site was used by the surrounding community for farmers markets, performances, and art festivals (Austermuhle 2017; Maxit 2021). The Plaza exists today in a unique position within the Adams Morgan neighborhood but remains part of a unique Washington, DC urban fabric with a legacy of change and transformation. Situating the Plaza within Adams Morgan as well as Adams Morgan’s surrounding neighborhoods is critical to understanding its future in Washington, DC.

A Legal History

This section investigates the legal history of the Adams Morgan Plaza in a contemporary timeframe to fully answer the first research question of this study: What is the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition? This section focuses specifically on the second part of this question: the history of Adams Morgan Plaza after its re-acquisition. On June 16th, 2017, the Kalorama Citizens Association (KCA) and the neighborhood group Adams Morgan for Reasonable Development (AM4RD) filed suit against the private development firm Hoffman & Associates and SunTrust (the Defendants) to regain control of the plaza after it was sited for a new upscale housing project. In his original brief to the DC Superior Court, Paul Zuckerberg—a practicing attorney representing the KCA and AM4RD groups (the Plaintiffs)—noted that the Plaza was under the ownership of the neighborhood, who maintained and utilized the plaza over the many years prior.(Schwartzman 2020) Zuckerberg cited a letter that Perpetual Federal Savings and Lending wrote to the Adams Morgan community in 1976 to substantiate his claims. In it, Perpetual Federal Savings President Thomas J. Owen talked about the bank’s desire to provide a public space for neighborhood residents:

“Perpetual agreed to develop the property in such a way as to preserve its open quality, attractiveness and accessibility to the vendors that presently use it. Present calls for a bilingual branch housed in a modest three-story building placed as far back as possible in order to allow ample room for vendors and other open-air activities” (Owen 1976).

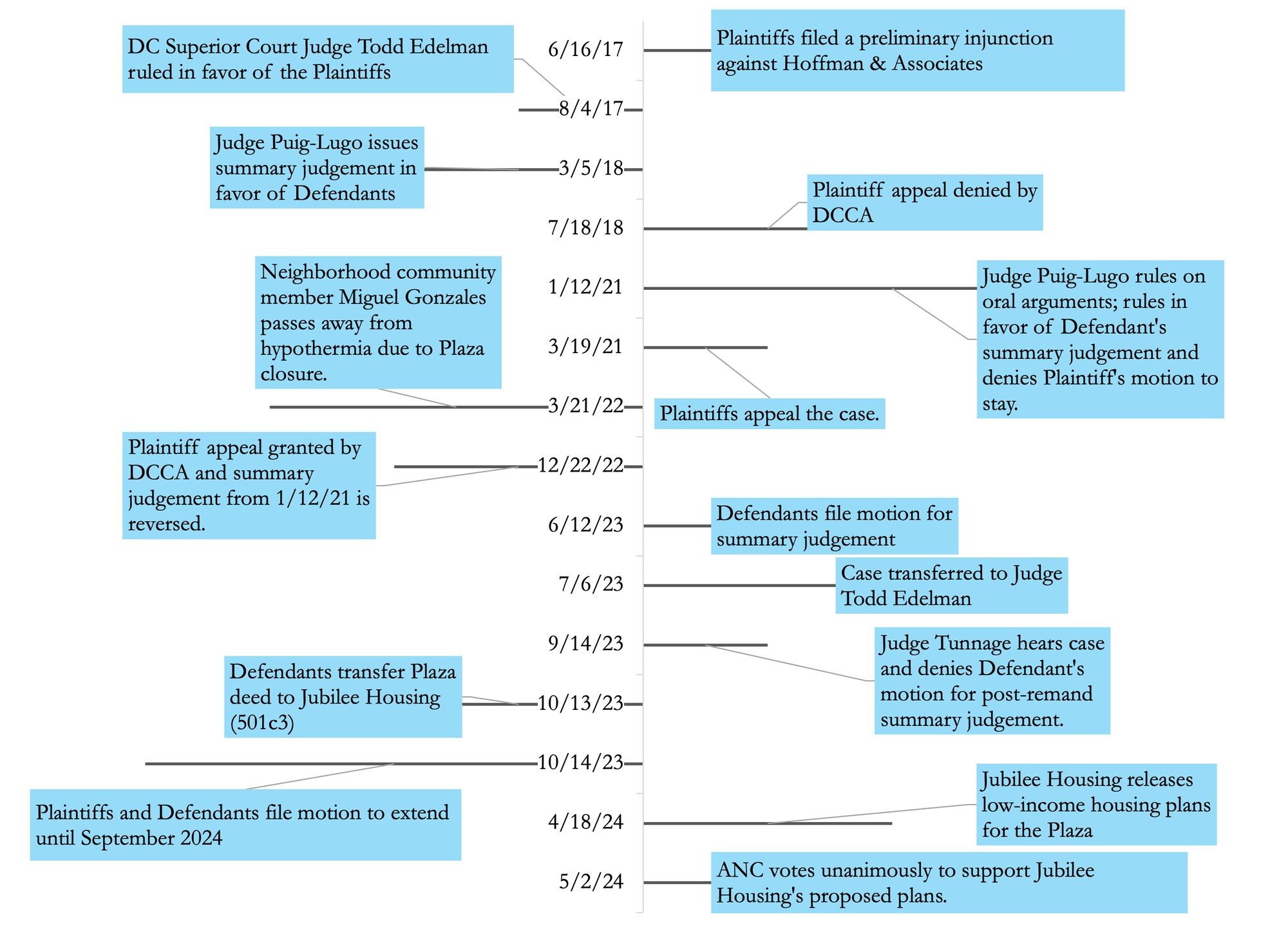

Citing Washington Land v. Potomac Ridge (2001), the Plaintiffs further argued that the Plaza met the necessary criteria to create a public easement: (1) an intent by the grantor to create the easement and (2) acceptance by the public (Zuckerberg, n.d.). On June 16, 2017—following his filing with the court—Plaintiffs filed a preliminary injunction against Hoffman & Associates to halt the potential demolition of the Plaza (Zuckerberg, n.d.). One week later, on June 23, Defendants filed documents opposing the preliminary injunction and calling for a summary judgment, arguing that “no genuine issue of material fact exists” and that “Defendants are entitled to judgment as a matter of law” (Jacobs 2017). On August 4th, DC Superior Court Judge Todd Edelman ruled in favor of the Plaintiffs and granted their request for a preliminary injunction to cease construction at the Plaza. He argued that the burden of proof to establish “no genuine issue of material fact” was on the Defendants, and not sufficiently argued in the Defendant’s earlier brief on June 26. Edelman noted that residents of Adams Morgan had a substantial chance of winning their lawsuit to stop the project and ordered Hoffman & Associates to stop further construction. The Court further denied the Defendant’s request for a summary judgment and instead ordered an expedited hearing for the case (Edelman 2017). On August 8, Edelman delivered another ruling again in favor of the Plaintiffs. He denied the Defendant’s earlier claims to require bond or compensation for potential losses incurred by the injunction granted on August 4. Edelman also established mediation sessions and a pretrial conference that would extend the timeline of the trial into 2018 (Edelman 2017). However, Hoffman & Associates would continue to delegitimize the claims of the neighborhood, beginning a 30-month tirade against the Plaintiffs to delay any future trial.

On December 29, 2017, the case was officially transferred to Judge Hiram Puig-Lugo after a series of back-and-forth hearings and filings between the Plaintiffs and Defendants over the previous four months (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017). Puig-Lugo handed down a few important decisions, including ordering a mediation session on January 10, 2018 (largely unsuccessful) and granting a summary judgment for the Defendants on March 5, 2018. Puig-Lugo’s ruling found that because Hoffman & Associates had no “proprietary interest in the property at issue,” the development of the Plaza would be subject to an “executory contract with SunTrust Bank” (Puig-Lugo 2017). Shortly thereafter, the Defendants filed a motion on March 7 to dismiss the case and move further proceedings to the US District Court for the District of Columbia (USDC) (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017). Zuckerberg and the original Plaintiffs filed an appeal almost two weeks later, and the case was brought to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals (DCCA) (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017).

Although the Plaintiff’s appeal called for a jury trial, the case was denied by the DCCA on July 18, 2018. Associate Judges Thomson and Glickman and Senior Judge Steadman wrote that the motion to dismiss the appeal was granted due to “lack of jurisdiction” (Glickman, Thomson, and Steadman 2018). In their opinion, the judges reference several previous holdings, including Reichman v. Franklin Simon Corp. settled by the DCCA in 1978. It found that although the Appellants in the case believed that an earlier summary judgment was issued prematurely, the lack of additional discovery in the case invalidated their claims to an appeal (Yeagley 1978). Thomson, Glickman, and Steadman drew parallels to Zuckerberg’s appeal case—supplemented by citations from the DC code—and affirmed their denial of his appeal. Almost two years later, the case was pushed from the USDC back to the District of Columbia Superior Court on September 25, 2020 (Caesar 2020). Judge Beryl A. Howell issued the memorandum opinion citing a lack of “subject matter jurisdiction” to hear the case at all (Howell 2020). Oral arguments were heard again before Judge Puig-Lugo and an oral decision was released on January 12, 2021. Puig-Lugo ruled in favor of the Defendants, denying Plaintiff’s motion to stay the proceeding and granting the Defendant’s motion for a summary judgment (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017). For three months, both Zuckerberg and Defendants went back and forth about bail payments before Zuckerberg appealed the case once again on March 19, 2021 (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017).

Following the reversal, fences went up around the Plaza almost a year later, on March 21, 2022 (Moyer 2022). On a freezing day later that month, unhoused Adams Morgan community member Miguel Gonzales passed away from hypothermia. Miguel Gonzales grew up in Adams Morgan and attended Oyster Adams Middle School only a short way away. In 2004, his building was converted into a co-op and while most residents took buyouts and moved, a member of Gonzales’ close family stayed. But when she died without a will in 2016, Gonzales was eventually kicked out because his name was not on the deed (Moyer 2022). From then on, Adams Morgan remained a central fixture of Gonzales’ life, as well as many other unhoused residents struggling to find permanent accommodation. When the plaza was cleared and fences erected, Gonzales’ belongings were lost. His death catalyzed widespread outrage in the Adams Morgan community, primarily aimed at Truist who many blamed for the wrongful death of Gonzales. Later that month, a graffiti-style mural (Figure 1) was created above the Plaza to protest the seizure of Adams Morgan Plaza that led to his death (Moyer 2022). Gonzales’ death was met with widespread sympathy and public outrage.

On December 22, 2022, the DCCA granted Zuckerberg’s appeal and remanded the case back to DC Superior Court to be heard in front of a jury (Schwartzman 2022). It further reversed the prior ruling on January 12, 2021, that granted a summary judgment to the Defendants in the case (Glickman, Thomson, and Steadman 2018). The ruling from the DCCA was released back to the DC Superior Court on March 3, 2023, after which the Plaintiffs filed a continuance to push the case for another two months (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017). On June 12, 2023, the Defendants filed another motion for a summary judgment (post-remand). In response, the Plaintiffs filed a motion to hold the case in abeyance because of Zuckerberg’s retirement from the law practice (KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al, n.d.). Puig-Lugo would deny the motion on July 6, 2023, but transferred the case to the care of Judge Donald Walker Tunnage (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017). Tunnage transferred the case back to Judge Todd Edelman, who originally heard the case; he accepted Zuckerberg’s motion to withdraw from the case on August 10, 2023, and heard the details of the case again from the Plaintiff’s new attorney, Amanda Fox Perry.(Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017) On September 14, Tunnage heard the details of the case from the Plaintiff’s new counsel and denied the Defendant’s motion for a post-remand summary judgment. One month later, SunTrust (now Truist) passed off the deed of Adams Morgan Plaza to Jubilee Housing, a nonprofit organization local to Adams Morgan on October 13, 2023. Both parties filed multiple motions to extend the case until September 6, 2024, while they negotiatec the use of the Plaza alongside Jubilee Housing’s construction plans (Superior Court of the District of Columbia 2017).

Jubilee Housing published their plans for the plaza on April 19, 2024. Their proposal included 40 low-income housing units on the Plaza as well as an open space to restore previous Plaza activities.(ERC Colbert & Associates 2024) Since then, numerous postings around the fences at Adams Morgan Plaza alert the surrounding neighborhood of Jubilee Housings plans:

“New 7-story mixed-use building with 1 cellar level and 1 penthouse level. Parking in cellar; retail at street level; apartments a 2nd-7th floors, and amenity space in the penthouse. A 4,095-sf public plaza is included at street level at the northern part of the site. The existing branch bank building and public plaza will be demolished” (from Figure 6).

Based on the current postings in and around Adams Morgan, the Plaza is set to remain a feature of the neighborhood. While the “existing branch bank building and public plaza will be demolished,” the notice intends to maintain the public plaza that has remained central to the Adams Morgan neighborhood community for the past 50 years. The visual plans for Jubilee’s project show a new, revitalized public plaza in front of its apartment complex (Figure 7).

On May 2, 2024, the Advisory Neighborhood Commission 1C (ANC) voted unanimously in favor of Jubilee Housing’s proposed project which was shared in a letter by ANC Chairperson Peter Wood (Peter Wood [@notPeterWood] 2024). The complex legal turmoil and attrition experienced across all levels of DC's court system undoubtedly weigh on the legacy of the Plaza (Timeline 1), but also exist against the changing economic backdrop of the neighborhood.

A Contemporary Economic History

To complement the legal history provided about Adams Morgan Plaza after its re-acquisition, economic census data is used to provide an answer to the second central research question of this study: what factors determined its future? In short, lowering poverty rates within the study geography before Hoffman & Associates re-acquired the Plaza, rising poverty rates within the study geography before Jubilee Housing took over the Plaza, and an increase in housing units in all but two of the census tracts of this study between 2017 and 2022 provide a potential resolution to this question.

Turning first to poverty rates, it is important to note that between 2016 and 2017—the year when Hoffman & Associates re-acquired the Plaza from SunTrust—poverty rates dropped in all but two census tracts within the study geography (Figure 8).

Census tracts 38 and 55 both saw an 11% increase in poverty rates between 2016 and 2017, while all other census tracts within the study geography observed decreases between 3% and 33%. The census tracts enclosing the area of the Plaza saw the smallest decrease in poverty rates, only a 3% drop in census tract 40.01 and a 14% drop in census tract 40.02. These respective drops in poverty rates might suggest that Hoffman & Associate’s desire to build upscale housing on the site of Plaza was motivated by improving economic conditions within the area. Decreasing poverty rates in the year before their acquisition of the Plaza area might provide positive reinforcement for Hoffman & Associates’ decision to build luxury—as opposed to public or low-income—housing. On the other hand, most census tracts saw an increase in poverty rates between 2021 and 2022 (Figure 8). All but four census tracts—38.02, 40.01, 55.01, and 55.02—saw poverty rates increase; they rose as little as 10% and as much as 260% during that time. In fact, the census tract enclosing the plaza (40.02) saw a 35% increase in poverty rates between 2021 and 2022 and so did most census tracts that surrounded the plaza. The directly neighboring census tracts 39.02 and 42.01 saw a 260% and 173% rise in poverty rates between 2021 and 2022 respectively. Only the other directly neighboring census tracts 38.02 and 40.01 saw decreases in poverty rates that were 46% and 42% lower respectively. The rise in poverty rates in the year before Jubilee Housing took over the Plaza might explain their choice to take over the site in October 2023. Further, these worsening economic conditions might have motivated Jubilee Housing to specifically propose low-income housing in April 2024 to address these issues.

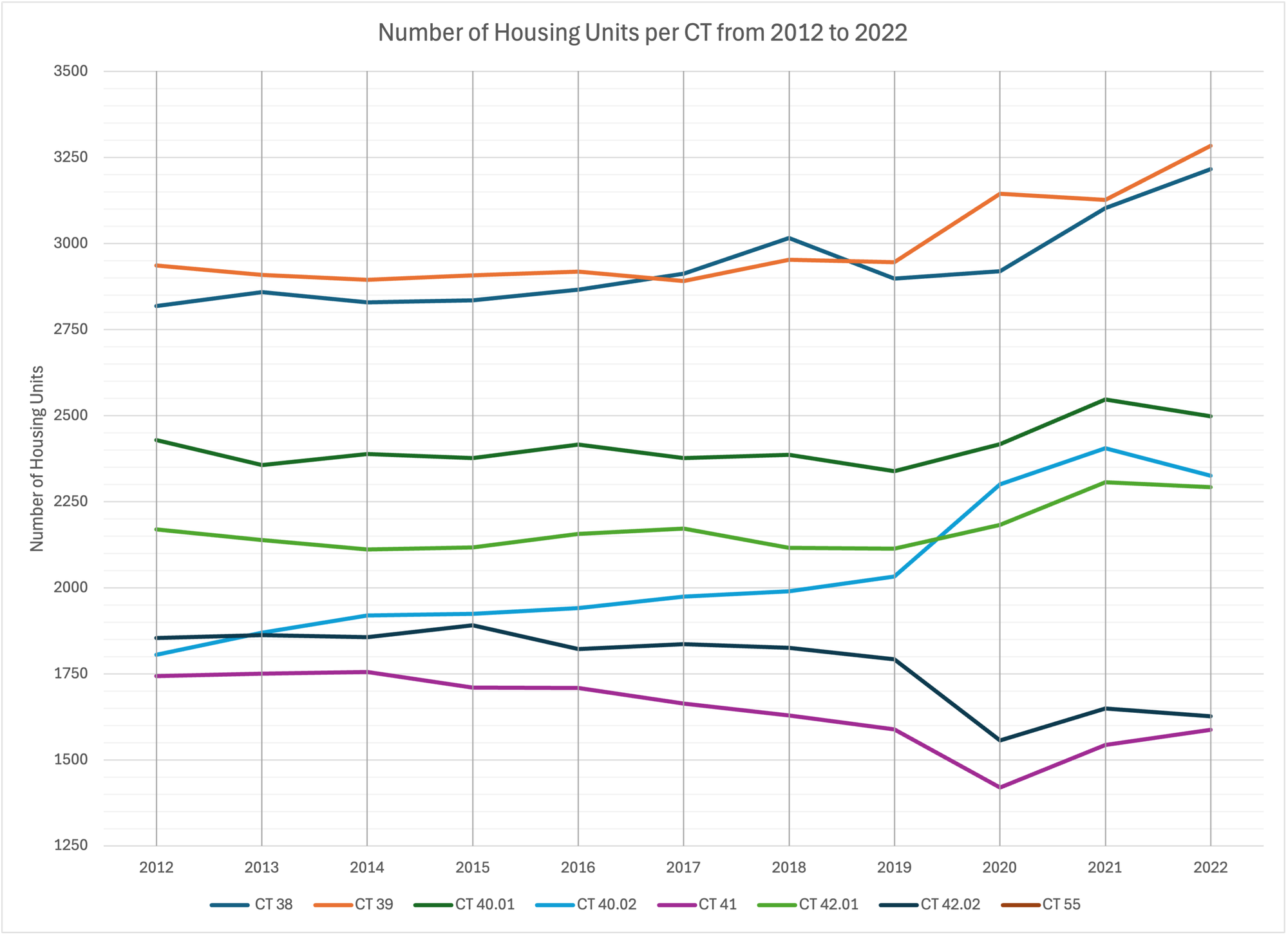

Considering the total housing within the geography of this study provides an additional parallel avenue to analyze both Hoffman & Associates’ and Jubilee Housing’s specific involvement in Adams Morgan Plaza. From 2012 to 2017—just before Hoffman & Associates re-acquired the Plaza—total housing units within the study geography remained relatively stable (Figure 9).

Hoffman & Associates’ involvement in the Plaza site comes before a rise in total housing units in most of the study geography between 2017 and 2022 (excluding census tracts 55 and 42.02 which saw a lower quantity of total housing units in 2022 than in 2017). Acquiring the Plaza site during a time when the number of housing units was relatively stable might have been advantageous for Hoffman & Associates who sought to make high returns on their construction project. Despite the jump in total housing units from 2017 to 22 in most of the study geography, poverty rates mostly worsened between 2021 and 2022. The simultaneous increase in housing units and poverty rates suggests that the housing units added from 2017 to 2022 did not address underlying economic issues within most of the study geography. This reinforces the hypothesis that Jubilee Housing’s involvement was precipitated by declining economic conditions and a rise in housing units that could not resolve the issue. Jubilee Housing’s involvement and commitment to building low-income housing would provide an intervention, giving DC residents “earning up to $90,400, or 60 percent of the area median income” to obtain stable housing and economic growth.(Schwartzman 2023) In numerous studies using predictive models, existing data analysis, and novel phenomenological analysis from the US and around the world point to the positive impacts that stable housing can have on economic well-being, quality of life, social cohesion, health, and job stability (Akinsulire et al. 2024; Marçal, Choi, and Showalter 2023; Tunstall et al., n.d.; Palimaru et al. 2023; Hudiburg 2022; Baumstarck, Boyer, and Auquier 2015). Affordable housing cannot single-handedly ameliorate poverty or produce widespread social benefits, but when coupled with other interventions—like housing placement experts and proactive policies—it can make a significant impact in places like Adams Morgan (“Housing Policy and Urban Inequality: Did the Transformation of Assisted Housing Reduce Poverty Concentration? | Social Forces | Oxford Academic,” n.d.; McClure 2008).

Based on the economic data evaluated in this section of the study, we can propose a possible answer to why Adams Morgan Plaza became involved in DC’s housing landscape. From 2016 to 2017, a drop in poverty rates throughout most of the study geography could have motivated Hoffman & Associates to re-acquire the Plaza for their luxury housing complex. Improving economic conditions in the year prior might create a favorable outlook for their plan, which sought high returns from a higher-income client base. At the same time, stability in total housing units between 2012 and 2017 might have inspired Hoffman & Associates to enter a stable landscape with little fluctuation in total housing metrics. Further, it is possible that Jubilee Housing’s involvement was precipitated both by rising poverty rates from 2022 to 2023 and an increase in housing units from 2017 to 2022 within most of the housing geography. An increase in housing units alongside worsening poverty rates might have encouraged Jubilee Housing to propose a low-income housing solution for the Plaza to mitigate the problem. These findings are reasonable assumptions based on the data from the study geography, but they are not conclusive or definite. Ultimately, Hoffman & Associates and Jubilee Housing are both private groups: a for-profit company and a 501(c)3 nonprofit, respectively. Their rationale for steering the Plaza’s future into the realm of DC’s housing landscape might have been motivated by a combination of different factors. The aforementioned data and analysis thereof offer only a possible explanation that accords with both the chronology and proposed goals of each company.

Conclusion

My historical inquiries show how the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition is plagued by two themes: punctuated equilibrium and conflict. Punctuated equilibrium is originally a term from biology used to describe evolution. It proposes that evolution did not happen gradually, but rapidly in short spurts followed by long periods of stability. This phenomenon describes the full story of Adams Morgan Plaza both before and after its re-acquisition. The early history of the Plaza is a story of rapid transition within the multicultural backdrop of the Adams Morgan Neighborhood. It experienced the tragedy of the Knickerbocker Theatre, the vibrancy of the Ambassador Theatre, the unsuccessful efforts of Perpetual Federal Savings Bank, and the desires of SunTrust bank to open a branch there after 1976. After 1976, the Plaza experienced a period of tranquility: the Adams Morgan community embraced its role as a public easement that offered ways for people to connect, socialize, and collaborate. For almost forty years, the Plaza existed as a public easement that brought joy to many. However, it would rapidly transition again, this time into the hands of Hoffman & Associates in 2017 when SunTrust decided to close their branch on 18th Street and Columbia Road. This was the moment when it entered the DC’s urban housing landscape. It was also when the Plaza’s history became plagued by conflict. The ensuing legal battle over the purpose of the Plaza plagued the site for almost seven years as the KCA and AM4RD waged a legal battle against Hoffman & Associates to preserve the public easement. The legal battle was so prolonged and thorny that eventually Jubilee Housing became involved in October 2023, solidifying the Plaza’s eventual purpose as a housing location. This final transition into Jubilee Housing’s hands would bring an end to the story of the Plaza and its history of punctuated equilibrium and conflict.

The economic data mobilized in this study proposes that poverty rates and changing quantities of housing units determined the future of the Plaza as a housing location. Early stability in housing units from 2012 to 2017 along with improving poverty rates from 2016 to 2017 in most of the study geography might substantiate Hoffman & Associate’s rationale to re-acquire the Plaza from SunTrust in 2017. A rise in housing units from 2017 to 2022 and increasing poverty rates from 2021 to 2022 in most of the study geography might explain Jubilee Housing’s involvement and proposal to build low-income housing. These data suggest a possible explanation for how the Plaza became a housing site, but do not offer a definite, undisputed rationale. Instead, the economic analysis of this study offers a potential insight into the other, more contemporary social histories that influenced the future of the Plaza.

The implications of this study are several. First, I elucidate the early history of an under-researched portion of Washington, DC that has undergone a series of rapid transformations. Secondly, I offer an in-depth history of the legal battle that has determined the future of Adams Morgan Plaza that surfaces important insights into the way urban space is historically disputed. These findings offer a history that can inform future, similar conflicts about the use and purpose of public space in urban environments. Thirdly, the economic analysis provided in this study offers a possible hypothesis about how public spaces like Adams Morgan Plaza are sited for housing projects. This element of the study provides a unique insight for future scholars to evaluate how housing is built, operationalized, and realized in multicultural, historical urban environments. Lastly, my investigation into the multilayered history of Adams Morgan Plaza provides a detailed narrative that pulls together many threads of journalistic, scholarly, and public inquiry. It offers a resource for future readers to return to the complex history of an important neighborhood fixture within one of DC’s most diverse neighborhoods.

This study invites potential future scholarship in similar areas of DC, where histories of housing, multiculturalism, and conflict are equally complex. The methods of this study aimed to use oral histories to supplement some of the findings, but the Plaza’s closure limited this endeavor. Future scholarly work might draw on oral histories following the completion of Jubilee Housing’s plan and their legal embroilment to give a more detailed history of the Plaza’s historic evolution.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Frank A. Guridy and Elizabeth Manchester who advised and supported the direction of this research. Their guidance and advice were critical to the success of this project. Additional thanks to Professor Claire Panetta and Professor Christian Siener from the Barnard College Urban Studies Program, who consulted heavily on this study from start to finish. I am eternally grateful for their advice while navigating the challenges and new frontiers of this research project.

Funding

Funding for this research study was generously provided by a Research Fellowship from the Eric H. Holder Initiative for Civil and Political Rights, an initiative of Columbia College of Columbia University.

Data Availability Statement

Census datasets, spreadsheet analyses, and generated charts are available to use at the link and at the request of the author by email: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LR0VVH. Original (digitized) legal documents and records used in this study are also available for viewing at the link and at the request of the author by email: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FPAKNC.

Declaration of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

Akinsulire, Adetola Adewale, Courage Idemudia, Azubuike Chukwudi Okwandu, and Obinna Iwuanyanwu. 2024. “Economic and Social Impact of Affordable Housing Policies: A Comparative Review.” International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences 6 (7): 1433–48. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i7.1333.

Austermuhle, Martin. 2017. “In Fight Over Future Of Adams Morgan Plaza, Groups Ask Judge To Look To The Past.” WAMU (blog). July 20, 2017. https://wamu.org/story/17/07/20/fight-future-adams-morgan-plaza-groups-ask-judge-look-past/.

Baumstarck, Karine, Laurent Boyer, and Pascal Auquier. 2015. “The Role of Stable Housing as a Determinant of Poverty-Related Quality of Life in Vulnerable Individuals.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 27 (5): 356–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv052.

Bryan, Rick. 2012. “Ambassador Theatre in Washington, DC - Cinema Treasures.” 2012. https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/7626.

Caesar, Angela D. 2020. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al v. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY. United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

Edelman, Todd E. 2017. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al. Superior Court of the District of Columbia.

ERC Colbert & Associates. 2024. “1800 Columbia Rd - HPRB Submission Set.” April 19, 2024. https://app.box.com/s/dhn9muwq7e6fqor5v5v40hn1w7yanfma/file/1511021738031?sb=/details.

Felix, Elving. n.d. “Research Guides: Knickerbocker Theater Collapse: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction.” Research guide. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-knickerbocker-theater-collapse/introduction.

Fraley, Jason. 2022. “Adams Morgan Vigil Marks 100th Anniversary of Knickerbocker Theatre Disaster.” WTOP News. January 28, 2022. https://wtop.com/entertainment/2022/01/adams-morgan-holds-vigil-to-mark-100-years-since-deadly-knickerbocker-theatre-disaster/.

Glickman, Thomson, and Steadman. 2018. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al (Decision from the District of Columbia Court of Appeals). District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

Gormly, Kellie B. 2022. “When a Winter Storm Triggered One of the Deadliest Disasters in D.C. History.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 26, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-a-winter-storm-triggered-one-of-the-deadliest-disasters-in-washington-dc-history-180979446/.

“Housing Policy and Urban Inequality: Did the Transformation of Assisted Housing Reduce Poverty Concentration? | Social Forces | Oxford Academic.” n.d. Accessed August 21, 2024. https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/94/1/325/1754291.

Howell, Beryl. 2020. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al v. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY (Memorandum opinion). United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

Hudiburg, Stephanie Keller. 2022. “The Role of Cross-Sector Collaboration and Longstanding Stakeholder Commitment in Organizing to Advance Cultural Community Development within the Context of Broader Economic Development: A Case Study of Deep Ellum Texas.” Local Development & Society 3 (1): 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2022.2045086.

Jacobs, Jonathan. 2017. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al (Motion for Summary Judgement). Superior Court of the District of Columbia.

KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al. n.d. Superior Court of the District of Columbia. Accessed August 12, 2024.

Krulik, Jeff. 2017. Flyer of the Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Ambassador Theatre. Digital Image. https://thekojonnamdishow.org/shows/2017-10-25/ambassador-theater-a-look-back-at-adams-morgans-psychedelic-history.

Leaman, Emily. 2008. “Washingtoniana: How Did Adams Morgan Get Its Name? - Washingtonian.” October 15, 2008. https://www.washingtonian.com/2008/10/15/washingtoniana-how-did-adams-morgan-get-its-name/.

Manning, Robert D. 1998. “Multicultural Washington, DC: The Changing Social and Economic Landscape of a Post-Industrial Metropolis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (2): 328–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198798330043.

Marçal, Katherine E., Mi Sun Choi, and Kathryn Showalter. 2023. “Housing Insecurity and Employment Stability: An Investigation of Working Mothers.” Journal of Community Psychology 51 (7): 2790–2801. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.23071.

Maxit, César. 2021. “Heart of Adams Morgan, DC.” Medium (blog). September 23, 2021. https://medium.com/@csrmxt/heart-of-adams-morgan-dc-a3f34dd49cbf.

McClure, Kirk. 2008. “Deconcentrating Poverty With Housing Programs.” Journal of the American Planning Association 74 (1): 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360701730165.

Moyer, Justin Wm. 2022. “Adams Morgan Mourns a Man Who Died Homeless, Steps from His Childhood Home.” Washington Post, May 10, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/05/07/dc-homeless-death-miguel-gonzales/.

Namdi, Kojo. 2017. “A Look Back At Adams Morgan’s Ambassador Theatre And Local Psychedelic History.” The Kojo Namdi Show. October 25, 2017. https://thekojonnamdishow.org/shows/2017-10-25/ambassador-theater-a-look-back-at-adams-morgans-psychedelic-history/.

Owen, Thomas J. 1976. “Letter to the Adams Morgan Community from Perpetual Federal Savings Bank,” November 2, 1976. 2017 CA 004182 B. Superior Court for the District of Columbia.

Palimaru, Alina I., Ryan McBain, Keisha McDonald, Priya Batra, and Sarah B. Hunter. 2023. “The Relationship between Quality of Housing and Quality of Life: Evidence from Permanent Supportive Housing.” Housing and Society 50 (1): 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2021.1928853.

Peter Wood [@notPeterWood]. 2024. “Last Night, Adams Morgan’s ANC 1C Voted Unanimously to Support Jubilee Housing’s Proposed Redevelopment of 1800 Columbia Rd NW, Home of the Former SunTrust Plaza It’s a Promising Step toward Redeveloping a Long Idle Property. Here Are Some Important Details We Learned ⬇️ Https://T.Co/5y4XVcY6wt.” Tweet. Twitter. https://x.com/notPeterWood/status/1786068241514746202.

Puig-Lugo, Hiram. 2017. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al (Order granting summary judgement to Defendants). Superior Court of the District of Columbia.

Schwartzman, Paul. 2020. “Judge Rules That Groups Have No Legal Standing to Fight Adams Morgan Project.” Washington Post, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/judge-rules-that-groups-have-no-legal-standing-to-fight-adams-morgan-project/2020/09/23/b54830ba-fdc3-11ea-9ceb-061d646d9c67_story.html.

———. 2022. “A Battle over an Adams Morgan Plaza Gains New Life with Court Ruling.” Washington Post, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/12/22/adams-morgan-plaza-dc-court-ruling/.

———. 2023. “A Long-Disputed Property in D.C. Changes Hands, but a Question Remains.” Washington Post, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/10/09/truist-bank-plaza-adams-morgan-owner/.

Schweitzer. 2017. “When Adams Morgan Was An Epicenter Of Counterculture In D.C.” WAMU (blog). November 22, 2017. https://wamu.org/story/17/11/22/adams-morgan-epicenter-counterculture-d-c/.

Superior Court of the District of Columbia. 2017. “Register of Actions - 2017-CA-004182-B.” Timeline. https://portal-dc.tylertech.cloud/app/RegisterOfActions/#/C2B3192C1EBA345B1B6B6068A20048C2198CA320F07677D1CF7680F3DDACFA8C2BC303FEA95FA789FBE5E1525B646941A0A15A8712BC0B80351BE89C816DD42DBDAAE18A6E4E4622EB378712D8E852C6/anon/portalembed.

The Library of Congress. 1922. Image of the Knickerbocker Theatre Collapse.

Tunstall, Rebecca, Mark Bevan, Jonathan Bradshaw, Karen Croucher, Stephen Duffy, Caroline Hunter, Anwen Jones, Julie Rugg, Alison Wallace, and Steve Wilcox. n.d. “The Links between Housing and Poverty: An Evidence Review.”

US Census Bureau. 2022. “Chapter 11: Weighting and Estimation.” In American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey Design and Methodology, 3:1–31.

———. n.d.-a. “B25001: Housing Units - Census Bureau Table.” Accessed August 18, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT5Y2022.B25001?q=washington, dc&t=Housing Units&g=010XX00US_040XX00US11_1400000US11001003800,11001003801,11001003802,11001003900,11001003901,11001003902,11001004001,11001004002,11001004100,11001004201,11001004202,11001005500,11001005501,11001005502,11001005503&d=ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables.

———. n.d.-b. “Census Bureau Search.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://data.census.gov/all?t=Housing:Housing%20Units:Income%20and%20Poverty&g=010XX01US_040XX00US11,11$0500000_1400000US11001004001,11001004002,11001004100.

———. n.d.-c. “S1701: Poverty Status in the Past ... - Census Bureau Table.” Accessed August 18, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2022.S1701?q=washington, dc&t=Poverty&g=010XX00US_040XX00US11_1400000US11001003800,11001003801,11001003802,11001003900,11001003901,11001003902,11001004001,11001004002,11001004100,11001004201,11001004202,11001005500,11001005501,11001005502,11001005503.

———. n.d.-d. “When to Use 1-Year or 5-Year Estimates.” Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/guidance/estimates.html.

Warf, Barney, ed. 2010. “Urban Spatial Structure.” In . 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412939591.

Wolf Trap. 2017. “Ambassador from Beyond the Third Rock: The 1967 Jimi Hendrix Debut in Washington, DC.” Wolf Trap All Access (blog). August 16, 2017. https://allaccess.wolftrap.org/2017/08/16/ambassador-beyond-third-rock-1967-jimi-hendrix-debut-washington-dc/.

Yeagley. 1978. Reichman v. Franklin Simon Corp.,. District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

Zapata, Celestino, and Josh Gibson. 2006. Adams Morgan. Then & Now. Charleston, S.C: Arcadia Publishing.

Zuckerberg, Paul. n.d. KALORAMA CITIZENS ASSOCIATION et al Vs. SUNTRUST BANK COMPANY et al (Motion for Preliminary Injunction). Superior Court of the District of Columbia. Accessed August 12, 2024.