Access Denied: Exploring Security, Community, and Belonging in University Spaces

When most people think of a campus in New York, they tend to think they are integrated throughout town, mixed in with the skyscrapers and business of the city. However, Barnumbia can lock all its entrancesinto campus, closing itself off from the surrounding neighborhoods and residents of Harlem.

Introduction

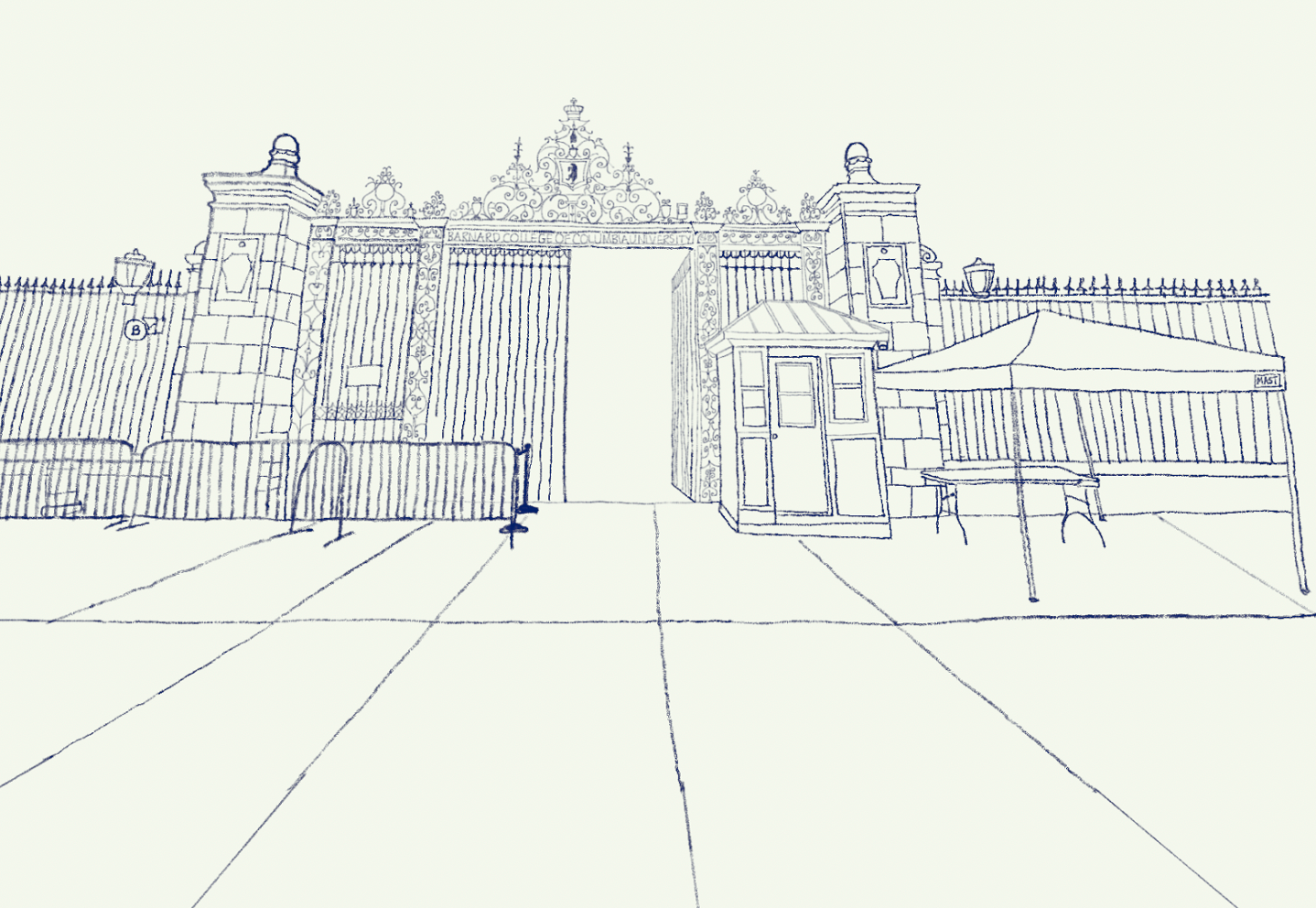

I leaned against a street pole just outside the Barnard main gates on 117th and Amsterdam, notebook and pen in hand, trying to catch the interactions between guards and students as they scanned their IDs and moved through the campus entry. Occasionally, someone without an ID would be pulled to the side and directed to the guard in the tent for a more thorough check. The gate felt like a divide between two worlds: the intimate community of a small liberal arts historically women’s college of Barnard and the bustling city of New York. I approached the guard in the tent during a lull and hesitantly introduced myself, explaining my project. He offered me a seat, and suddenly, my role as observer slipped away, replaced by the warm chatter of his unasked-for stories and thoughts.

“[You] have to have some order to it,” he said, explaining why the college’s security presence had become more visible this year. He spoke with pride about knowing the students by name, about seeing them grow and ensuring their safety, despite others viewing these measures as intrusive. Our conversation shifted from security protocols to his seventeen years at Barnard to his memories of move-in days and the promises he made to nervous parents. He seemed less a guard than a guardian, a figure who blurred the line between policing and protection, between restriction and belonging. As I left for my first class of the day, I was completely struck by the information I had received on my first day of observation. I realized just how much there was to uncover about this security mechanism surrounding campus. For instance, upon immediate reflection, this guard resembled the “public characters” Jane Jacobs speaks of: “anyone who is in frequent contact with a wide circle of people.” One that “is public… and makes himself available to lots of different types of people” (Jacobs, 1961). This reference reveals how these smaller occurrences, characters, and physicalities in and around Barnard and Columbia’s main gates are microcosms of broader city life and their realities.

As a current sophomore at Barnard College, I have frequentlywalked through both Barnard’s main gates at 117th St and Broadway and Columbia’s main gates at 116th St and Broadway (together coined “Barnumbia”). Last year, I lived on Barnard’s main campus, so my entry point to my dorm was through the main gates. In addition to these entrances, I have walked through many gates, doors, and exits of the university. When most people think of a campus in New York, they tend to think they are integrated throughout town, mixed in with the skyscrapers and business of the city. However, Barnumbia can lock all its entrances into campus, closing itself off from the surrounding neighborhoods and residents of Harlem. I remember reassuring my parents of their safety concerns about living in a large city, explaining this security systems aas an attempt to quell their discomfort. What I did not realize then was that Barnumbia would act on this power and restrict all of campus to only those with Columbia University or Barnard College IDs (CUBCIDs).

As a result of last semester’s protests, including an encampment on the south lawn and the occupation of Hamilton Hall, Barnumbia announced a change in entrance restrictions at the beginning of the school year. Before these protests, the main gates were open and accessible to anyone, with few exceptions. On August 29th, Barnard students received an email from the administration outlining the new restrictions. They announced that “to ensure that Barnard remains a welcoming and safe place for our community to live and learn…We will start the semester at Level B.” This new level means that “Barnard’s campus is open to everyone with BC and CU IDs” and “advance guest registration is required.” They followed this by stating that they “will adjust the campus status to reflect current circumstances and to take into account any information or potential events that could affect the College.” This vague wording and language completely changed access to campus alongside community mood and attitude.

Setting and Methods

As a student on campus throughout this change in access, I hoped to research its impact. My main field sites include Barnard’s main gates at 117th and Broadway and Columbia’s main gates at 116th and Broadway. As I continued my research, I began to observe additional entrances and exits to both campuses subconsciously; these observations helped to supplement my initial sites and added to the depth of research on movement across campus. From standing outside and inside these gates, hearing stories from friends and peers about their experiences, having conversations with guards like the one illustrated above, and analyzing communications from university administration and the responses they provoked from the student body, I have come to understand how these new security mechanisms function as both physical and symbolic barriers. I argue that Barnard and Columbia's access restrictions implemented after the spring 2024 protests have had contradictory impacts: they have heightened surveillance and policing of students while simultaneously fostering closer ties between the university community and public safety officers. These restrictions reveal inconsistencies in their enforcement, calling into question their purpose and rationale within broader discussions of security, exclusivity, and belonging on college campuses.

Literature, Major Findings, and Themes

These entrances are a part of my everyday life as a Barnard student. However, it was not until I slowed down and observed the gates that I realized the stark differences between the way Columbia and Barnard operate their access points, as well as the inconsistencies in all gate operations. On initial impression, the major difference were the security guards. At Barnard, the front gate was equipped with security guards who are public safety officers and have worked at the college for many years.

“Underneath this tent sat another guard with a table and a couple of chairs. Both guards were Black men in Barnard uniforms…I asked him [the security guard under the tent] how long he had been working here. [I was completely taken aback when he said seventeen years. I was even further surprised] when he called the guy in the hut asking how long he had been here and he responded with thirty-nine years.”

These employees have been a part of the Barnard community for so many years, decades for some, so it felt like they had a real interest in the well-being and safety of the community. One of my first observations resulted in a conversation with a Barnard guard outside the main gates, where he subtly hinted at the differences between Barnard and Columbia’s security operations.

“‘On this side of the street we take your safety to heart here, once you’re here you’re family’” (Security Guard).

Perhaps he was implying that Columbia which is on the other side of the street, and its security guards do not care as much about their community. Nevertheless, he was clearly emphasizing how Barnard values safety. I took his comment more seriously when, upon, observing Columbia’s entrance, I immediately noticed a big difference.

“All seven of these officers are wearing Allied Universal uniforms. [I’m assuming this means Columbia hires them from an outside security firm, as opposed to using already hired public safety officers. Because they have so many more entrances and a greater number of people entering and exiting than Barnard, they must need more officers than they had prior to the new restriction policies.]”

In addition to the variation between the guards at each school, there are many differences in each entrance’s operation. The main entrances at Barnumbia always have officers standing outside and require every person entering to scan their IDs. Sometimes the guards will check the photo on someone’s ID to confirm it is them, but other times, they just check to make sure the ID scans. Other entrances to Barnard’s campus, such as the back entrance to Milbank and the entrance to Milstein on Claremont Ave., only require scanning an ID. I have never seen any guards at these entrances, so hypothetically, a CUBCID holder could swipe in outside guests or hold the door open for non-CUBCID holders. Therefore, how are students supposed to perceive and understand what security is if it is enacted and enforced in different ways?

In contrast to Barnard, security guards are at all of Columbia’s entrances. Some of these entrances are not even access points but are still guarded. Similarly, these guards will check to see if the ID photo matches its owner, yet other times, they only check if it scans. One time, I was leaving campus from the Northwest Corner Building on Columbia’s campus and exiting onto 121st Broadway. This entrance usually has multiple guards outside, but there were none, so anyone could enter with the help of a CUBCID holder.

These are just some of the inconsistencies I have noticed, but from hearing from peers and friends, I am confident that these irregularities occur frequently across the two campuses. If these new restrictions fail to meet their goal of ensuring only CUBCID holders are allowed on campus, why impose them in the first place? Columbia and Barnard’s administrations must be aware of these inconsistencies, but I have not noticed any attempt to rectify them. If the university is not enforcing these restrictions to ensure safety, what is the real intention behind them? Are they meant to ease psychological discomfort rather than guarantee physical safety? These questions about intention and security implementation mirror broader patterns in how universities historically respond to perceived threats.

In Eric Coleman’s work, he explores how universities navigate the challenge of balancing security measures that affect students' safety, civil liberties, and access while striving to protect community members and uphold institutional values of inclusivity and student rights. Coleman argues: “In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, colleges and universities across the United States began implementing more stringent security measures that affected students' civil liberties and access to campus facilities” (Coleman, 2009). These changes mirror Barnumbia's current restrictions, though the catalyst differs significantly. Unlike Coleman's example of 9/11 where the threat to safety was clear and resulted in the deaths of thousands, the new restrictions at Barnumbia were based solely on the recent occupation of an academic building, lacking any comparable immediate danger to justify the new measures. These changes were implemented as a preventative measure to suppress possible further action instead of being a reactionary measure like Coleman’s 9/11 example. The comparison raises critical questions: What constitutes a threat, and what level of response is appropriate? Are there inconsistencies in safety codes when different groups are targeted? For instance, would the same security measures apply if white Jewish students led an encampment or hall occupation?

When I began my field site observations, the primary impact that stood out to me was that those without CUBCIDs couldn’t access campus. When I started making these observations at the beginning of the semester when these rules had just been implemented, many non-university stakeholders hadn’t fully understood the implications of the changes in restrictions.

“Many people wander up to the guards sitting under the tent to the right of Barnard’s main gate. I’m not close enough to hear their conversations but they point to the line of students waiting to tap into campus with a confused look on their faces. [I assume they are asking what’s going on] Most of these people are walking dogs or have children, [they seem familiar with the area.] Even those who aren’t trying to get onto campus are questioning the change to their neighborhood streets. [These restrictions already are affecting community members.]”

Davarian Baldwin, a scholar who focused on observing the impacts of universities on their surrounding areas for much of his career, presents Columbia as a perfect example of universities being active participants in the development of cities. This exacerbates gentrification and urban inequality. He argues that “...universities have become the dominant employers, real estate holders, policing agents, and healthcare providers in major cities” (Baldwin, 2021). This makes them active participants in urban displacement and gentrification. Over time, Barnumbia has continuously expanded into Harlem. Specifically its recent developments of its Manhattanville campus have caused residents, typically from low-income and marginalized backgrounds, and businesses to be displaced and kicked out of their neighborhoods. Another important point made by Baldwin is that these universities typically have outward-facing missions of service and social justice. This is entirely hypocritical as they often have incredibly harmful effects on local communities. Before the new restrictions, it was common to see families, people walking dogs, and other members of the local community utilizing campus spaces. Columbia takes up an important space in the community as it occupies all of the land between 114th and 121st between Broadway and Amsterdam. The only way to cross these avenues is through campus. With the closure of the campus, residents and the outside community have no way of connecting the eastern and the western sides of this massive campus besides going around it. This further places Barnumbia in an “ivory tower” as it both disconnects itself from the area of Harlem and disconnects the area of Harlem from accessing space in their own neighborhood. It is important to note that Columbia is the largest private landowner in the entire New York City yet pays almost no property taxes; not only does this institution affect its surrounding neighborhood, but the entirety of the city (Haag and Kolodner, 2023). Additionally, the fragmentation of the neighborhood because of Barnumbia’s expansion has been further emphasized by increased security personnel in and around campus. This increase is meant to not just protect the university community but to also increase their control over the area, even among stakeholders not a part of the university. This control by security officers have shaped the movement of stakeholders, forming physical lines across campus aided by the implementation of barricades.

“As the time approached 10:00 am a larger rush suddenly emerged of those entering and exiting campus. Before a line even began to form, the guard inside of the hut motioned and yelled to the crowd to form a line wrapping up the block in front of the tent. This line followed a line of barricades. There was a lot of pointing and commotion, but the scene soon settled into a seamless line. This line, well long, going back at least 20ft, moved swiftly and steadily. People walked up to the gate from the opposite direction of the line, realized there was a line, and then proceeded to walk to the end of it. [There was a natural, almost synchronized nature to this flow of movement.] A woman tried to cut and was immediately told to go to the back of the line by the guard in the hut who yelled, ‘No cutting!”’

These new mechanisms reflect broader patterns of institutional control and behavioral change within university settings. The modern university system, as analyzed by Kupchik and Monahan in "The New American School," increasingly employs advanced surveillance and control mechanisms that normalize constant monitoring and prepare students for highly structured environments. While their study primarily examines primary and secondary education, similar patterns are seen in higher education settings like Barnumbia. The university's use of ID cards, surveillance cameras, and on-site officers creates a extensive infrastructure that ultimately shapes students' relationships with authority and their understanding of belonging. These mechanisms condition students to accept constant monitoring, comply with authority, and believe that this is the norm beyond the gates of university. This psychological conditioning becomes evident in daily behaviors:

“Today I attempted hybrid ethnography. I walked up to the hut and told the guard I had forgotten my ID. He asked for my UNI and looked me up on a computer. After verifying who I was he motioned to another guard to let me go through. As I walked though the pathway built by barricades I, without hesitation or realizing, tapped my ID on the scanner and entered campus.”

Having to tap my ID every time I enter campus has become so engrained that even when I did not need to, I still did it subconsciously, revealing the power these surveillance mechanisms have over behaviors and thoughts which. Many people have not yet considered the long term effects the new restrictions will have on students and university community members. Still, in connection with this study, it is clear that heightened surveillance mechanisms have much deeper implications. Through creating a controlled university campus space, community members are at risk of conforming to social ideals of surveillance and compliance over genuine engagement. This raises the question of whether these measures truly aim to foster a safer campus or instead serve as methods of control of student movement, activism, and community integration.

From my perspective, the new restrictions across both campuses feel like checkpoints and a way to further police campus after the real police inhabited campus at the end of last semester.

“A girl walked by me and in reaction to the length of the line said “Oh my fucking god,” to no one in particular.”

Instead of providing safety, they feel like a punishment and a way to stop students from exercising their right to freedom of speech and protest. I have seen this sentiment echoed by many of my friends and peers at on- and off-campus protests calling for a Free Palestine and to Defend Harlem. When talking with the Barnard security guard, I posed this question to him, wondering what his take was as a Barnard employee of seventeen years.

“I asked candidly if he liked the new restrictions of this year. His answer was yes [which didn’t surprise me but his reasoning did.] He said he has gotten to know the student body way more by putting names to faces. He ‘likes to communicate’ with the students by giving them nicknames or learning about their lives; these new restrictions have allowed him to do so. He said that the ‘more we know the students, the more they will agree to security rules.’ He saw them build up the community and bring himself and the other guards closer to the stakeholders of the school.”

I saw this guard act on his words while I talked to him. Other Barnard Public Safety officers displayed a similar sentiment toward the Barnard community.

“A young woman walking her dog scanned her ID and entered the gate with the guard in the hut waving and saying hello….A woman approached the guard at the tent asking for directions for a building and he pointed her in the right direction wishing her a good rest of her day.”

In most of the dialogue on campus, the questions always focus on how the new restriction has affected students. Rarely does it consider the public safety officers, who are arguably just as important to the campus community. This guard’s perspective was unanticipated and completely altered my perspective as I progressed in my observation, making me look at the gates through a new lens.

“[From what I have heard and experienced from other students, we view these restrictions as a new form of policing. And while we can acknowledge the guards don’t make the decisions, they still enforce them and so are grouped into this concept of policing.]”

I have worked hard to examine my positionality as I enter these spaces. I think about the impact of my research on my community. The security guard I talked to hesitated to answer certain questions for fear of his job, revealing the sensitivity of this topic. This also indicated that he knows he is an active player in this enforcement despite his community-building claims. This conversation highlighted the power dynamics at play. Typically, security guards hold power over their stakeholders in monitoring them, but as our conversation continued, there was a shift to myself holding power regarding his job security. To what extent can these guards and universities foster a sense of community without acknowledging these complex power dynamics at play?

Power dynamics have a profound impact on students' sense of belonging and inclusion on their college campuses, as seen in both Trevor Ward and Michiyo Samura’s work. Ward focuses on “academic safe spaces” and argues that they are essential to creating spaces of belonging and inclusivity (Ward, 2017). He defines these spaces as opportunities for those from marginalized backgrounds to have the freedom to express themselves without fear of harassment or suppression. Like the secure but accessible spaces Ward describes, Barnumbia's gated environments create a controlled space to ensure safety, but they raise questions about who is excluded and why. The contrast between Ward’s idea of fostering inclusion and Barnumbia’s physical and administrative barriers highlights the complexities of creating a genuinely inclusive campus environment. With access to academic safe spaces on campus limited or completely cut off for many, students face many more obstacles to freely expressing themselves and finding a common community.

Samura’s study on Asian American student's relationship with college campuses adds to this point. She introduces the concept of "spatial capital" to describe students' ability to access and utilize campus spaces, directly impacting their feelings of inclusion or exclusion (Samura, 2018). Additionally, she examines how students perceive public and private spaces on campus differently and can reinforce or challenge existing social hierarchies. Institutional policies, like Barnumbia’s access restrictions, impact not only how students see themselves but also how they perceive their place in the broader campus and community. They construct notions about who belongs on campus and who does not. These access policies do more than regulate who can enter; they shape the social dynamics of the university and its surrounding neighborhood, reinforcing divisions and challenging the concept of an inclusive campus.

Proposal For Future Research

I hope to continue this work and expand it even further since this process has opened the door for more questions and potentially, further research. I would like to spend more time closely observing all the entrances and exits around campus instead of just the main ones. I would also like to go to the Manhattanville campus on 125th to see how it might differ from the main campus. A lot of the insights and stories I built my work upon were given to me by friends and their experiences. I think this project would greatly benefit by employing team ethnography because of the many entrances and exits. There are so many stories of inconsistencies and variations that I did not have the space to include in this paper even though they would add to my findings. I hope to include them in future work. This topic of study is new considering the very recent protests that erupted across college campuses around the world in the spring of 2024. When looking for outside sources to reference, I struggled to find relevant studies because of the novelty of this topic. If possible, I think doing a comparative study of different college campuses, observing their reactions to the protests and then the impacts they had on their students, would greatly add to this work. Therefore, I hope to publish this work to be a reference for future studies. Finally, I struggle to balance the ethics in this research. Writing about the inconsistencies across campus could inspire Barnumbia to tighten control, to ensure their rules are being enforced as intended, an impact that is not an intention of my work.

Conclusion

Through this research, I’ve learned that the gates at Barnumbia are not just physical barriers. They are symbols of power, control, and community. They enforce the duality of the university’s roles as both an inclusive academic institution and an exclusive entity prioritizing security of new perceived safety threats. This duality creates a paradox: while aiming to foster safety within the campus community, the gates simultaneously alienate those outside of them, contributing to Barnumbia’s growing gentrification and exclusionary presence in Harlem. Furthermore, these gates represent how institutions of higher education navigate protests and dissent, choosing to implement surveillance and control as opposed to engaging with the demands of student activists through good-faith dialogue. It is clear that this approach not only affects campus dynamics but has broader implications for the societal role that universities play: agents of change and enforcers of social norms.

Are the gates a means of fostering community, as some guards suggest, or are they barriers that reinforce divisions within the university and between the university and its surroundings? My research suggests it’s both, and understanding this duality is key to navigating complexities of safety, community, and control in university spaces.

References

Baldwin, Davarian L. “The University as Landlord.” In In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities, 59-85. New York: Bold Type Books, 2021.

Coleman, J. Eric. “Policing the College Campus.” In Policing America’s Educational Systems. New York: Routledge, 2019. ISBN 9781315155715.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

Kupchik, Aaron, and Torin Monahan. “The New American School: Preparation for Post‐Industrial Discipline.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 27, no. 5 (2006): 617-631.

Samura, Michiyo. “Remaking Selves, Repositioning Selves, or Remaking Space: An Examination of Asian American College Students' Processes of 'Belonging'.” Journal of College Student Development 59, no. 4 (2018): 456-473.

The New York Times. “Columbia University and Its Tax-Free Empire.” The New York Times, September 26, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/26/nyregion/columbia-university-property-tax-nyc.html.

Ward, Trevor N. “Protecting the Silence of Speech: Academic Safe Spaces, the Free Speech Critique, and the Solution of Free Association.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 26, no. 2 (December 2017): 557-xxx.